By Louise Irvine

In the last few months, many of us have sought solace in gardens but as summer draws to a close and flowers wilt and fade, we are fortunate to have many lasting memories encased in crystal at WMODA. Paul Stankard, the living master of flame-working, has been inspired by his own garden and poems about flowers and nature by Emily Dickinson and Walt Whitman.

Paul Stankard

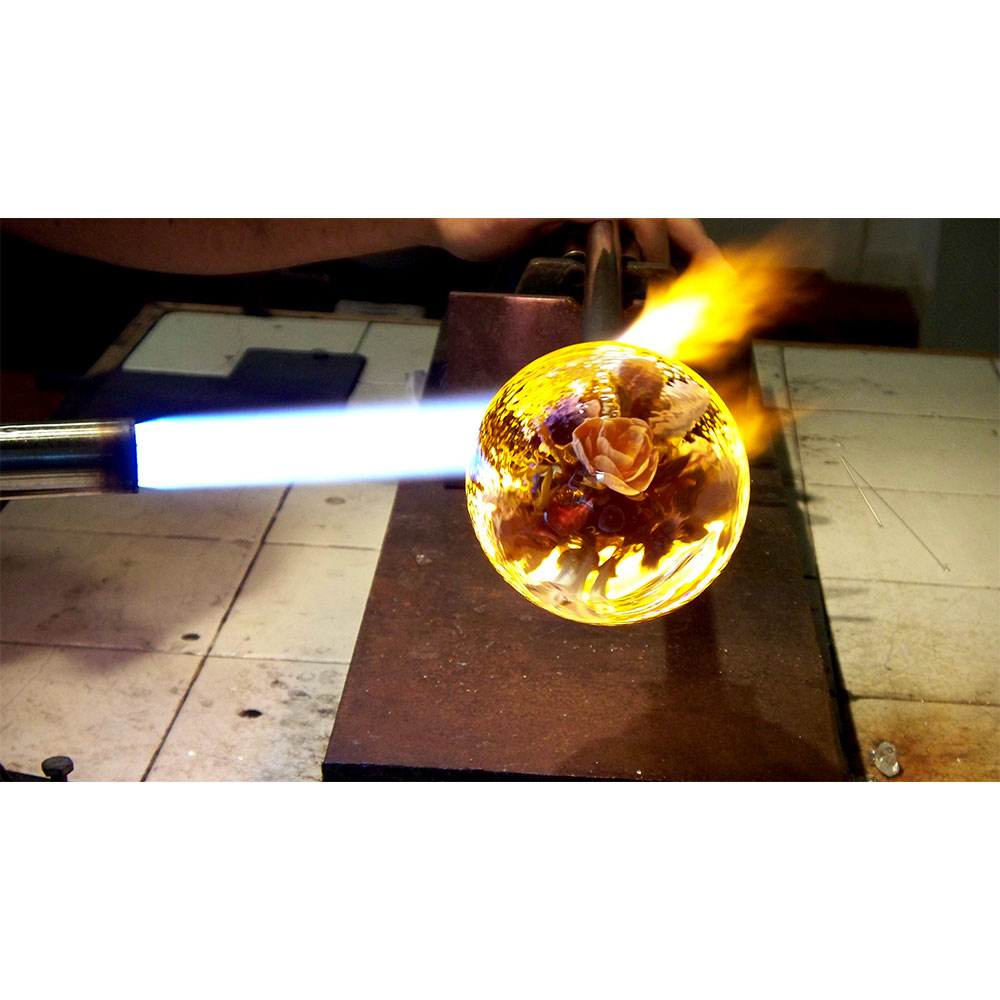

Paul Stankard uses a gas oxygen bench torch and rods of glass to make tiny petals and pistils, which he assembles into complex floral clusters. He encapsulates his miniature gardens in molten glass, which is then cooled, cut, and polished to form paperweights, orbs, and other sculptural forms. His tiny glass flowers and insects are executed so perfectly that they almost seem real. However, his miniature works of art are often fantasies, integrating his interest in botanical realism with spiritual mysticism and the cycle of life.

Paul endeavors to capture in glass shared feelings about nature that he finds in poetry, literature, and art by creative people who have touched his soul. His lovingly rendered studies have been described as narratives of the soul and visual poems to the splendors and mysteries of the natural world.

Paul Stankard

Paul Stankard at work

Paul Stankard at work

Paul Stankard at work

Pineland Bouquet

The Healing Virtue of Beauty: A Meditation

Paul Stankard

Being cloistered at home during the pandemic has offered me a peculiar benefit: I immersed myself working in the studio next door in a renewed spiritual fervor. Oddly enough, despite being isolated because of my heightened medical risk factors, I have derived a sense of restoration and well-being while exploring the healing virtues of beauty during my quarantine. I have encountered a confluence of my interest in translating Walt Whitman’s and Emily Dickinson’s poetry into glass, and a heightened consciousness in the qualities of transcendentalism.

Transcendentalism is an elusive philosophy. For me, it means evidencing nature in a spiritual realm, combined with a disciplined work ethic and individualism. Incorporating transcendentalism as a creative goal could seem abstract, but to me, the process is to render my feelings into a physical glass object that celebrates the healing virtues of beauty.

My interest is not new. It has been percolating for decades. But because of my solitude and creative need I have enabled the spiritual energy of Whitman and Dickinson to impregnate my work. Over the course of my career, I have likened my activity in the studio to a monk-like devotion. Faced with being isolated, I now have a better understanding of the value of cloistered spiritual focus.

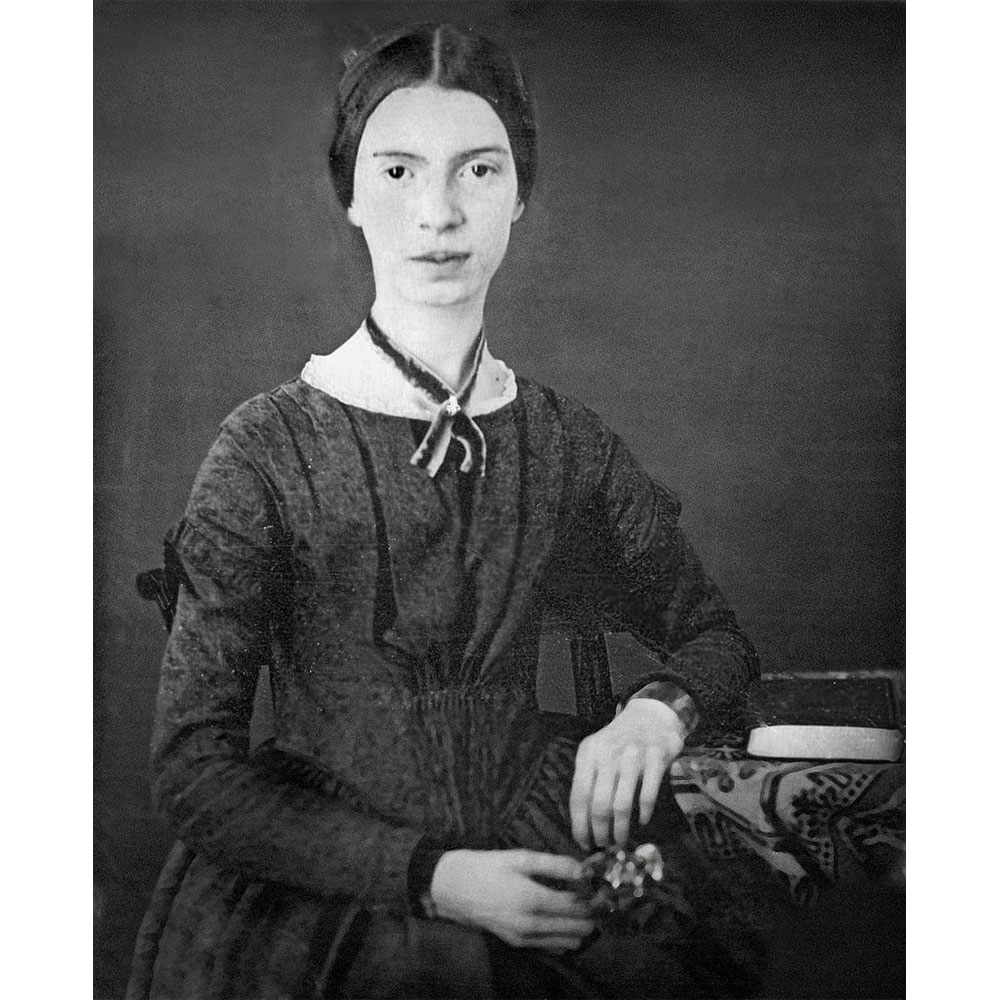

Emily Dickinson (1830-1886)

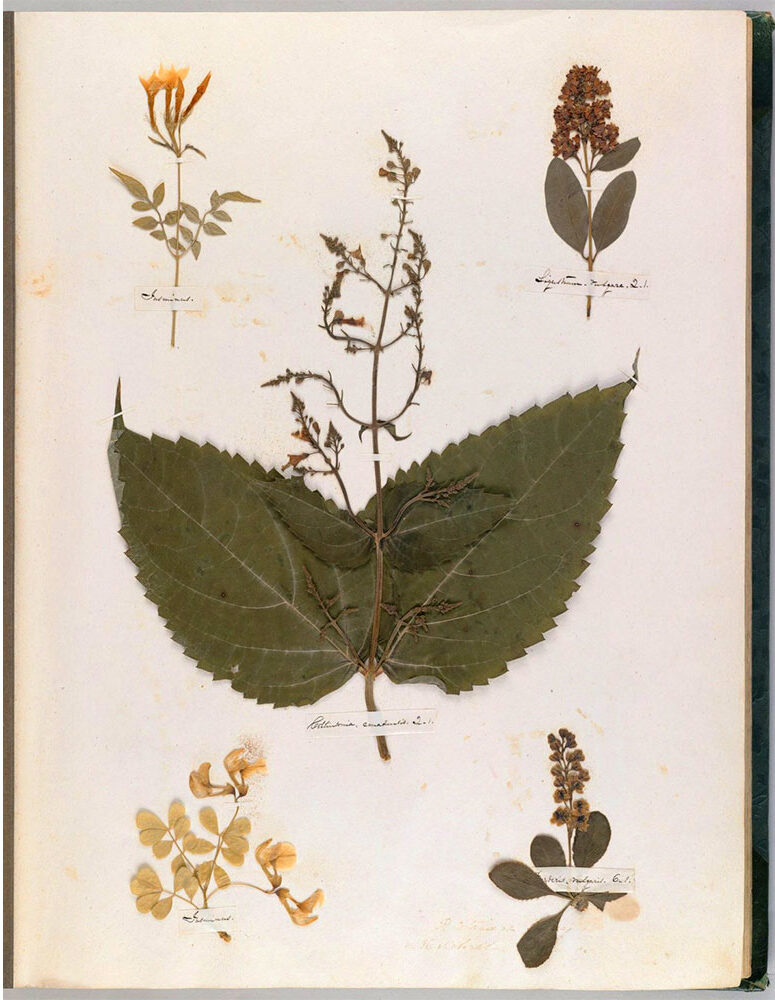

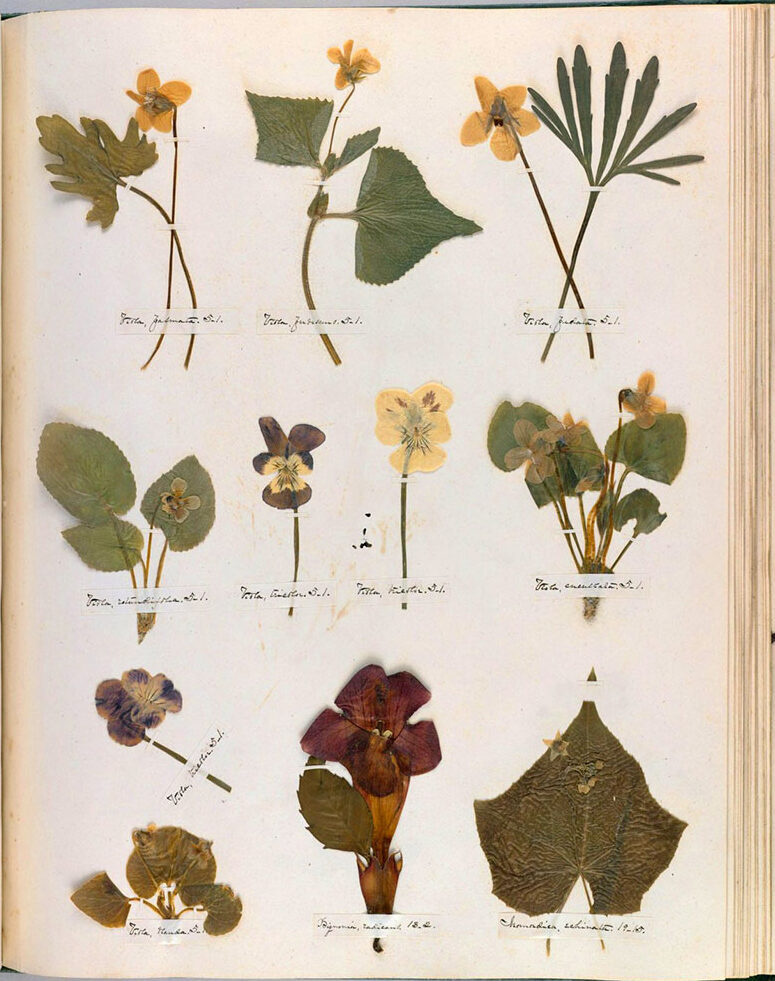

Paul’s crystal orb at WMODA, entitled Emily Dickinson’s Secret Garden, brings the reclusive poet’s words and pressed flowers into a new dimension. Long before she began writing the poems that established her reputation, Emily Dickinson studied botany. Like many young girls in the 19th century, she was encouraged to gather, classify, and press flowers. She began her studies at the age of nine and started to assist her mother in the garden when she was twelve. Her exquisite herbarium contains 424 flowers and is known today thanks to the digitized volume produced by Harvard Libraries.

The opening page of her herbarium features tropical jasmine, which was grown in her family’s New England greenhouse along with gardenias, carnations, and ferns. In the Victorian language of flowers, jasmine symbolizes poetry and passion, premonitions of Dickinson’s later writing. Meadow wanderings introduced her to flowers closer to home such as buttercups and clover. Violets were among her favorite flowers and eight different varieties are lovingly pressed in her herbarium. Violets were associated with humility, and she holds a clutch in her photographic portrait.

Throughout her life, Emily was a keen gardener and grew flowers, vegetables, and fruit on her family’s property which is now being restored by the Emily Dickinson Museum. Plants often feature in Miss Dickinson’s poetry and it is her combination of words, images, and love of nature which appeals to Paul Stankard.

Emily Dickinson’s Secret Garden Orb

Emily Dickinson's Garden Bouquet with Honeybee *New Work

Emily Dickinson's Ethereal Bouquet *New Work

Emily Dickinson

Emily Dickinson's flowers

With a Flower

Emily Dickinson

When roses cease to bloom, dear,

And violets are done,

When bumblebees in solemn flight

Have passed beyond the sun,

The hand that paused to gather

Upon this summer's day

Will idle lie, in Auburn,

Then take my flower, pray!

Emily Dickinson's flowers

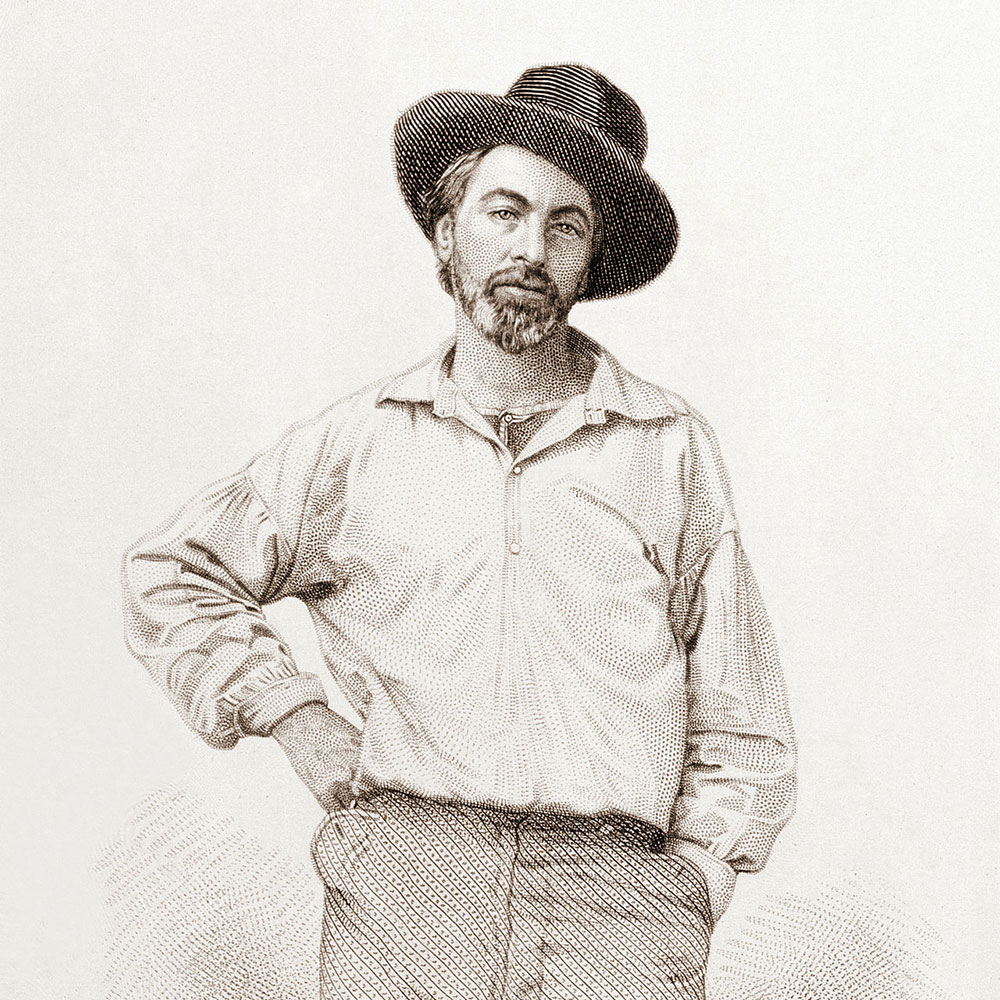

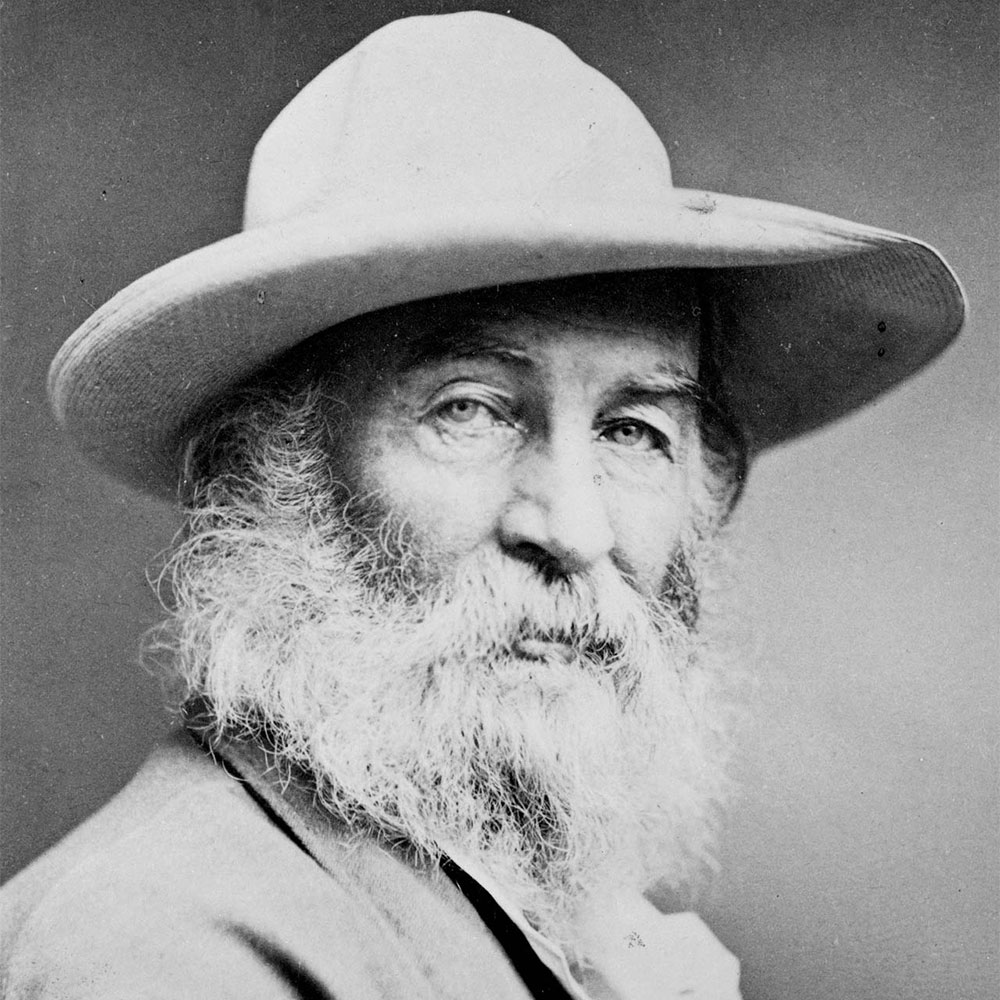

Walt Whitman (1819-1892)

When Paul Stankard first encountered Walt Whitman’s writing in the late 1980s, the effect was visceral, and he refers to Whitman as the patron saint of his studio. Many of Paul’s crystal orbs were inspired by Whitman’s poetry, which articulates a mystical depth of feeling about Mother Earth bridging the earthly and the eternal. Floral clusters and swarms of bees capture the dance of life in Paul’s Homages to Walt Whitman and his anthropomorphic roots teem with fertility.

Whitman’s exuberant poem Song of Myself in his book Leaves of Grass is regarded as an American literary classic. It celebrates the joy and wonder of nature and humanity’s place within it. Whitman embraced his environment and his stream of consciousness writing style, with its free association of thoughts, enhanced his mood of unity with nature and the divine.

Like Whitman, the environmentalist, Paul loves the timelessness of nature, walking in the woods, wading through streams and swamps, where he can experience the subtle hum of nature. Lines from Whitman’s Leaves of Grass have personal resonance for Paul.

“A morning-glory at my window satisfies me more than the metaphysics of books.”

“Give me odorous at sunrise a garden of beautiful flowers where I can walk undisturbed”

“You are so much sunshine in every square inch.”

Whitman’s words seem to be reflected in Paul’s life and works and could easily describe his glowing crystal orbs. Paul has often been inspired to put pen to paper and express his thoughts and memories of the natural world around him.

No Green Berries or Leaves

by Paul Joseph Stankard

Walking north

along the tracks

past Lily pond,

thistles mark

the narrow path

through grass

moist in morning dew.

To the blueberry woods,

where filling a quart container

brought praise

for no green berries or leaves,

as a mother smiled

on a child’s labor.

Now gathering blueberries

like a prayer,

the first taste

a communion,

the mystery shared.

Homage to Walt Whitman Orb

Homage to Walt Whitman

Walt Whitman Garden Orb

Morning Glory with Golden Orb

Walt Whitman engraving

Walt Whitman

"No Green Berries or Leaves" book by Paul Stankard

Read more about Paul Stankard and

The Art of the Flame exhibition at WMODA.

Photos courtesy of Mike Brodie; Lauren Garcia; Houghton Library, Harvard; Jeff DiMarco; and Paul Stankard.

*Contact WMODA if you would like more information about Paul Stankard's new work.