By Louise Irvine

The Jabberwock was one of the most frightening creatures that Alice met in the dream world that she discovered Through the Looking Glass. The monster has been visualized many times since Sir John Tenniel created the defining image for the first edition of Lewis Carroll’s book in 1871. As we celebrate the sesquicentenary of Alice’s adventures at WMODA, we are highlighting Royal Doulton’s renowned sculptor of Jabberwocks, Mark Valsler Marshall, (1842-1912).

When Alice climbed through to the other side of the mirror one wintry afternoon, the pictures appeared to be alive, the clock had the face of an old man, and the chessmen were walking about. The White King had fallen into the fireplace and when Alice rescued him, she found his memorandum book. Initially, it appeared to be written in a language that she didn’t know until she realized it was a looking-glass book and she had to hold the pages up to a mirror to read it. Even with the words the right way around it didn’t make sense and she found it hard to understand. However, one thing was clear to her somebody killed something. The poem begins…

Jabberwocky

‘Twas brillig, and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe;

All mimsy were the borogoves,

And the mome raths outgrabe.

Beware the Jabberwock, my son!

The jaws that bite, the claws that catch! ...

The surreal, random poem is full of nonsense words coined by Lewis Carroll some of which were explained to Alice by Humpty Dumpty later in the book. For example, slithy means lithe and slimy, and brillig is four o’clock in the afternoon. He also described some of the strange creatures such as the Borogrove which is a shabby bird, the Tove which is a cross between a badger, a lizard, and a corkscrew that feeds on cheese, and the Rath which is a kind of green pig.

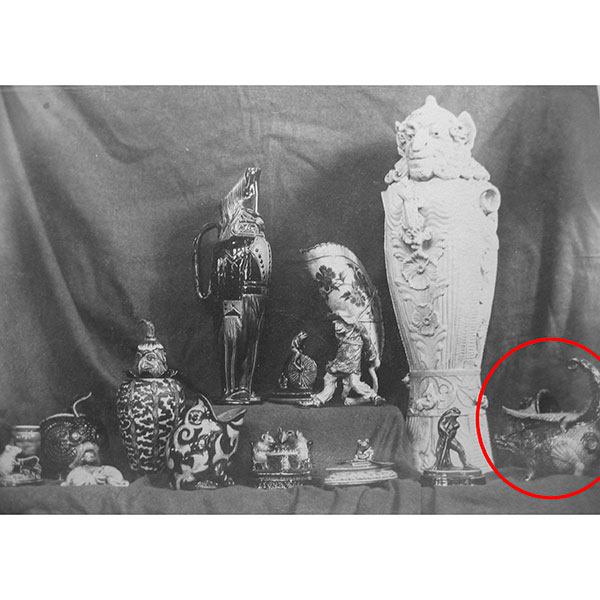

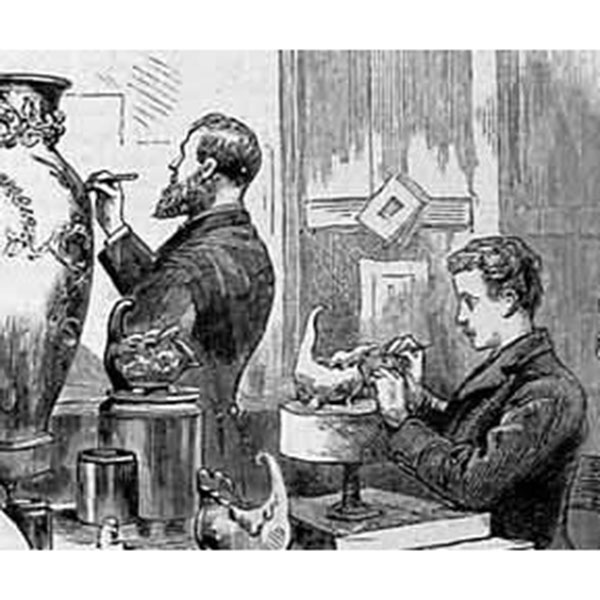

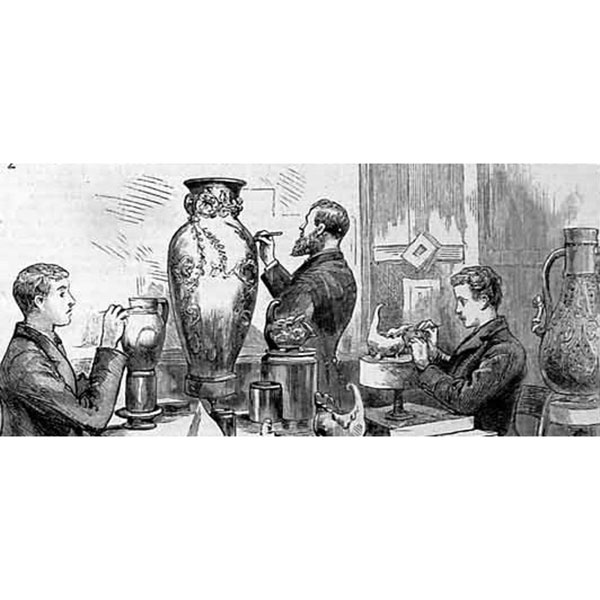

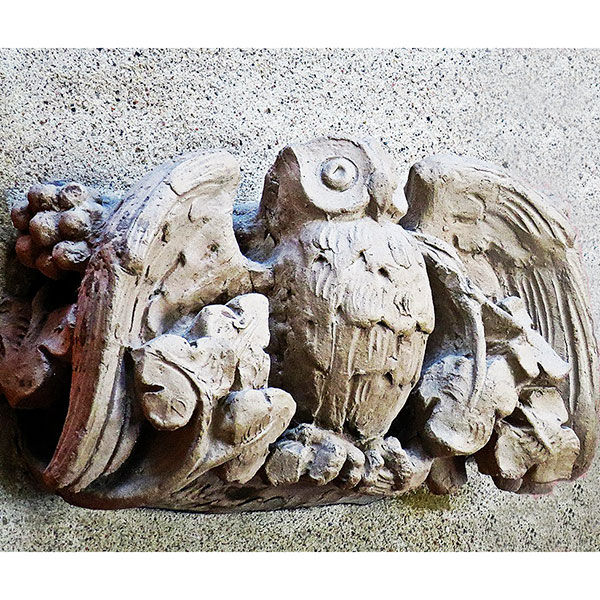

At Doulton’s Lambeth Art Pottery in London, Mark Marshall visualized the Rath in salt-glazed stoneware with a pig-like snout emerging from leafy foliage. In the Graphic illustrated newspaper of 1886, Marshall is depicted with one of his assistants decorating a Rath, which was produced in several color variations. It was also featured in the London Humorous exhibition of 1889 along with one of Marshall’s extraordinary pufferfish. In Marshall’s Wonderland, it was quite normal for fish to merge with seaweed, rabbits to morph into lettuces, and serpentine monsters to slither from slimy caves.

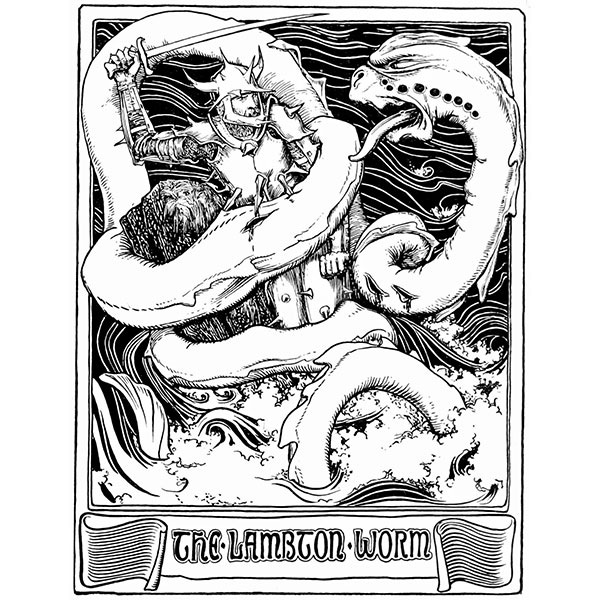

The Jabberwock, with jaws that bite, claws that catch and eyes of flame, “came whiffling through the tulgey wood, and burbled as it came!” Lewis Carroll is believed to have based the Jabberwock on the legend of the Lambton Worm, a medieval dragon that terrorized the North of England. Tenniel drew the Jabberwock as a whimsical dragon with rabbit teeth wearing a vest! His Jabberwock reflects the Victorian obsession with natural history especially fossils and paleontology. He gave his creature the scaly neck and tail of a sauropod and the leathery wings of a pterodactyl.

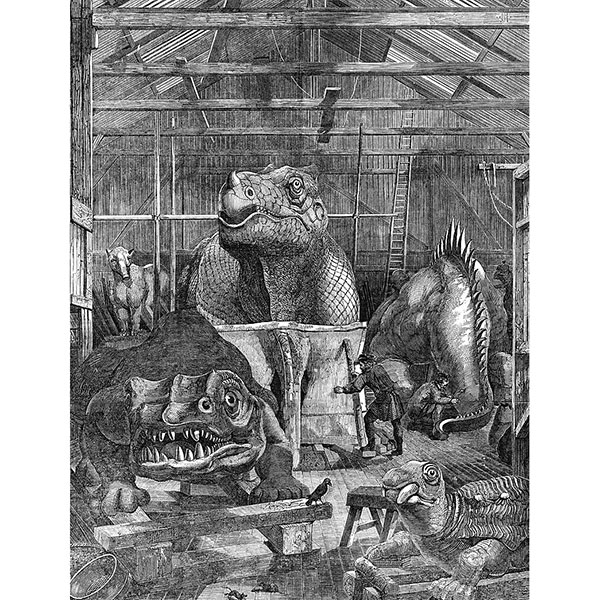

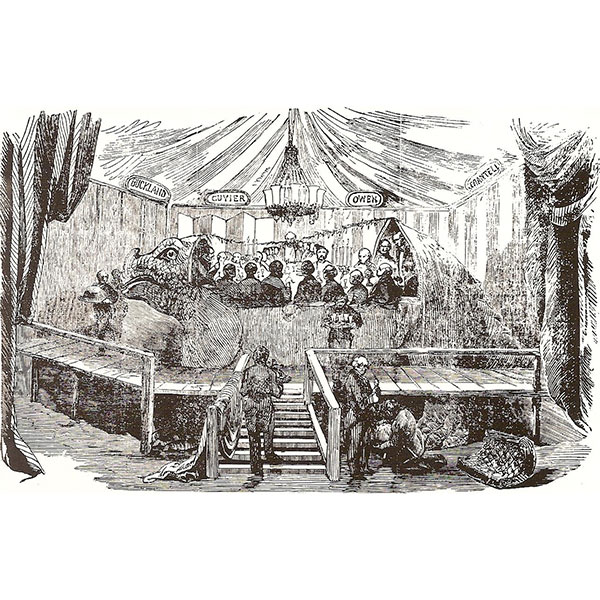

No doubt Tenniel was familiar with the giant statues of dinosaurs, the first life-size models in the world that were exhibited on the grounds of the Crystal Palace in South London. The “terrible lizards” were modeled in clay for casting in cement and in true Wonderland-style a banquet was held inside the mold for an Iguanodon to mark their launch in 1853. The dinosaurs captured the public imagination at that time and were made even more compelling by the rise and fall of the lake water four times a day so it looked as if the primordial monsters were emerging from a swamp.

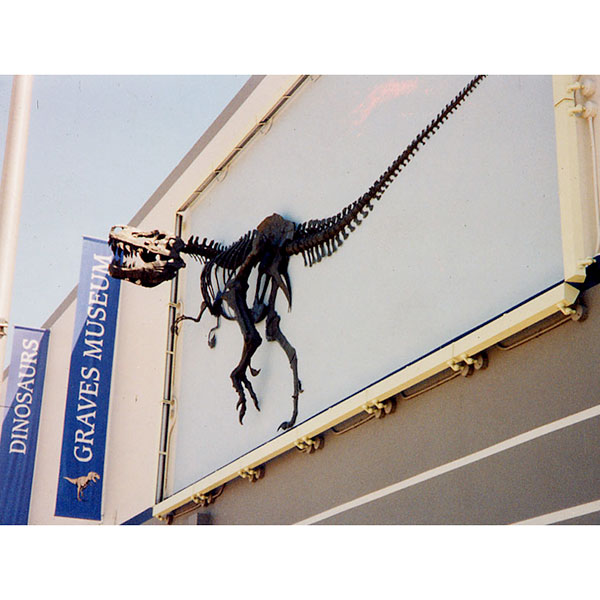

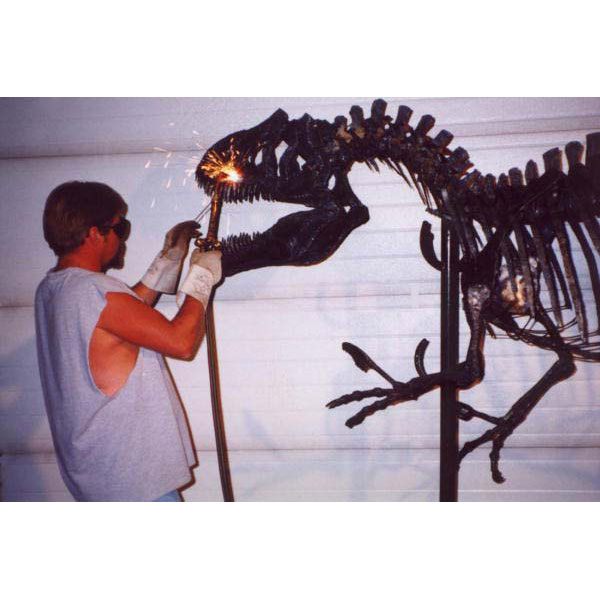

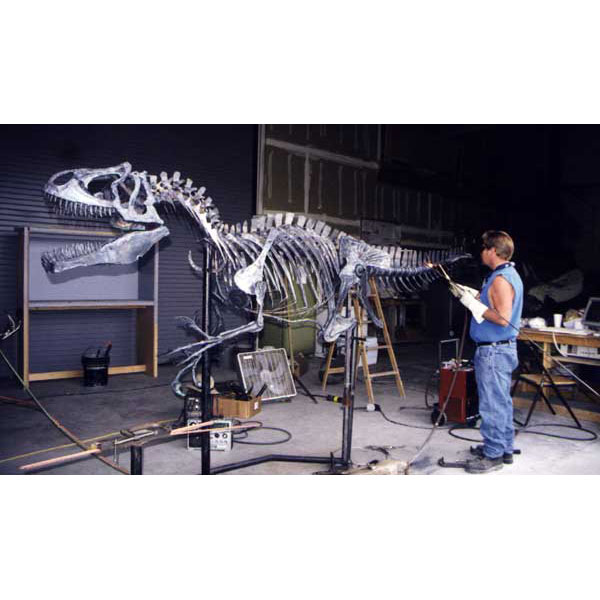

Curiously, a dinosaur is the landmark for WMODA dating back to the building’s former life as the Graves Museum of Natural History. The 30-foot-long steel Tyrannosaurus Rex was built by Californian dinosaur artist Larry Williams and has become iconic in the area. Although some kids are disappointed not to find dinosaur fossils inside the building these days, they can enjoy dragons, mermaids, and many other fantastical creatures in the Fired Arts on display in our WMODA Wonderland.

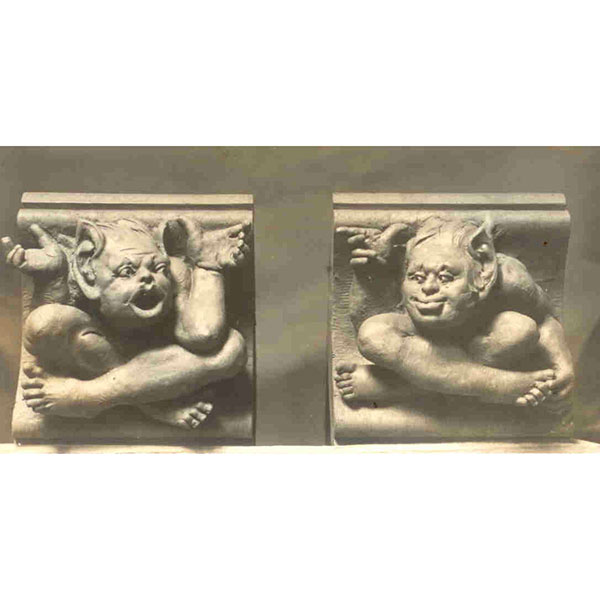

The Crystal Palace dinosaurs must have been familiar to Mark Marshall who lived nearby in South London. He was famous at the Doulton studio for his hybrid reptilian monsters which writhe around stoneware vases and bowls in Neo-Gothic style. A taste for the grotesque was fashionable in the Victorian era and Marshall developed his skill for portraying creeping and crawling creatures during his first career as a stone carver on Gothic revival churches.

The son of a mason from Cranbrook in Kent, Marshall worked with Farmer & Brindley, London’s leading architectural sculptors. He carved statuary of Christ and the saints for Salisbury Cathedral but had a life-changing experience when he stepped back on the scaffolding to see his work and nearly fell. He was so shaken that he had to be helped to the ground and determined never to work at heights again. His religious convictions were strengthened further in 1870 when he attended a Plymouth Brethren meeting with fellow sculptor Wallace Martin whom he met while attending classes at Lambeth School of Art and later at Farmer & Brindley’s. When work was slack at the stonemasons, Marshall was employed at the Martin Brothers Studio in Pomona House, Fulham for ten shillings a day. Although Marshall moved his young family to a cottage near the studio and considered becoming a partner, there was a concern that differing religious views would cause a sectarian divide at the pottery and he left after a few years.

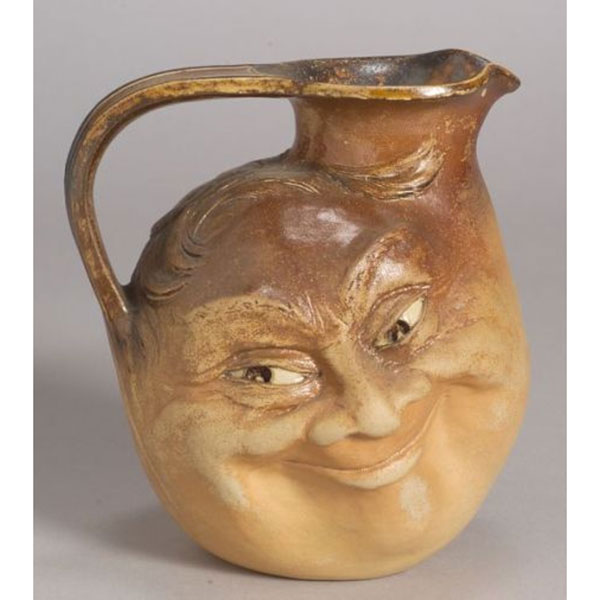

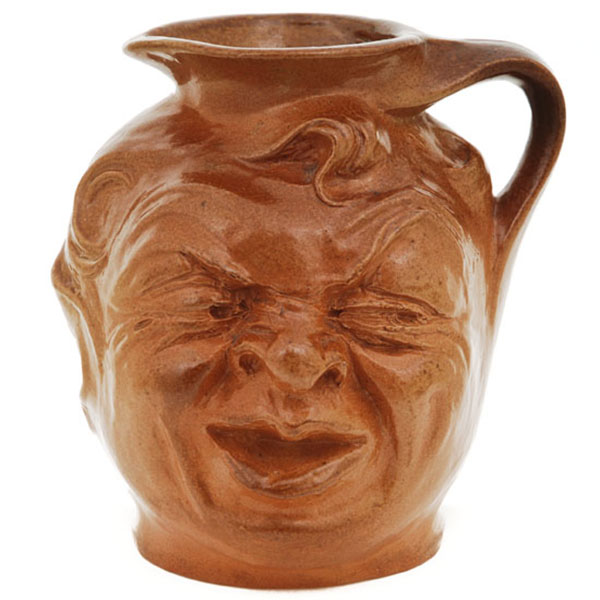

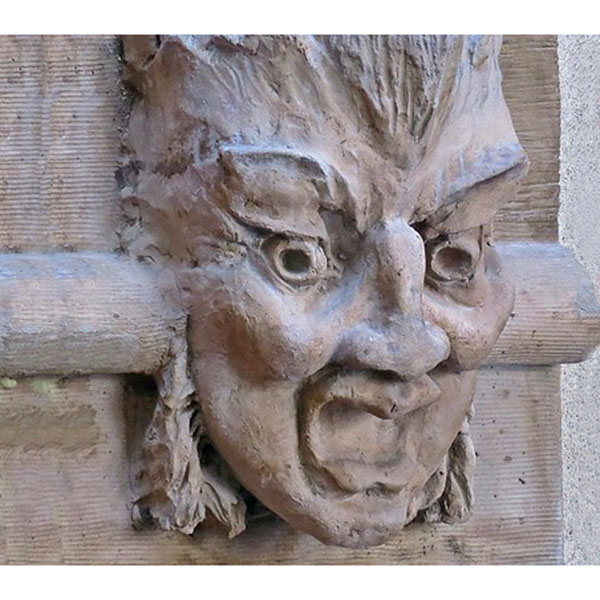

Marshall’s work for the Martin Brothers is not recorded and he complained when he was not acknowledged in the 1882 Magazine of Art article by the critic Cosmo Monkhouse who claimed, “who save Mr. Martin could give you a Boojum or a Snark in the round?” Like Marshall, the Martin Brothers were clearly inspired by Lewis Carroll’s nonsense poems including the Hunting of the Snark and there are many similarities in their work. Marshall made his own versions of Wally birds, grotesque monsters, and leering face jugs long after he left the Martin Brothers.

For a few years, Marshall worked for T.C. Brown, Westhead and Moore, a Staffordshire pottery with a studio in London. He produced several large majolica garden statues including dragons and wild animals, which were shown at the international exhibitions in Philadelphia in 1876 and Paris in 1878. The pottery won a gold medal for their exhibit in Paris and Marshall’s sculptures of near-life size tigers, which he modeled from life at London Zoo, received accolades in the contemporary press. Marshall first began working for Doulton’s Lambeth Studio around this time. The exact date is not known but there are Doulton pieces with his MVM monogram from 1879. WMODA has an undecorated figure of a beggar bear with its cub, which was attributed to Doulton but is a smaller version of a Brown, Westhead Moore majolica statue.

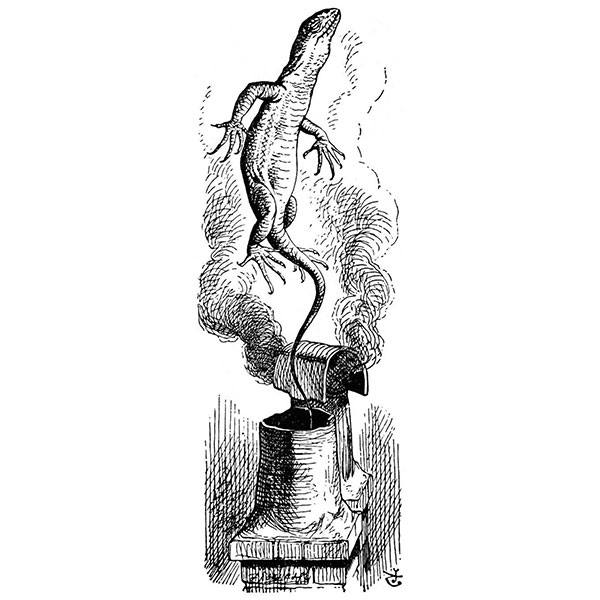

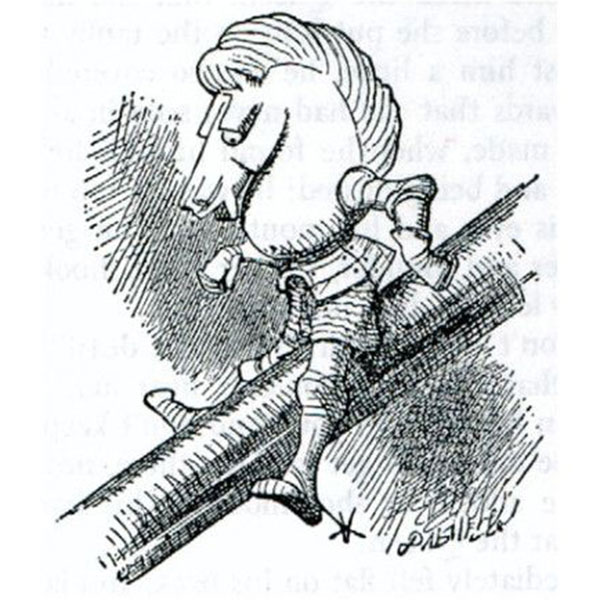

Marshall was obviously fascinated by Alice’s adventures in Wonderland and he modeled several bizarre paperweights of the Cheshire Cat, Bill the Lizard, the Mock Turtle, and the Chess Knight. The White Rabbit also influenced The Waning of the Honeymoon, which was made in several versions. The jaded couple is indicative of Marshall’s impish sense of humor which he shared with Lewis Carroll. Marshall’s rabbits reflect the Victorian fascination with the relationship between man and animals, prompted by Charles Darwin’s Origin of the Species. Cartoonists responded in the popular press with illustrations of all sorts of animals endowed with human characteristics. Taxidermists also contributed to this trend with elaborate tableaux and Queen Victoria was amused by a kitten’s wedding at the Great Exhibition of 1851. Walter Potter created similar scenes for his Museum of Curiosities, notably a village school populated by rabbits.

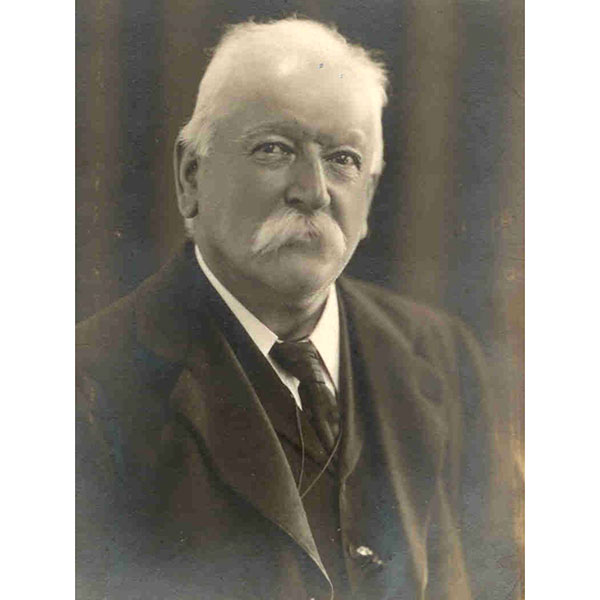

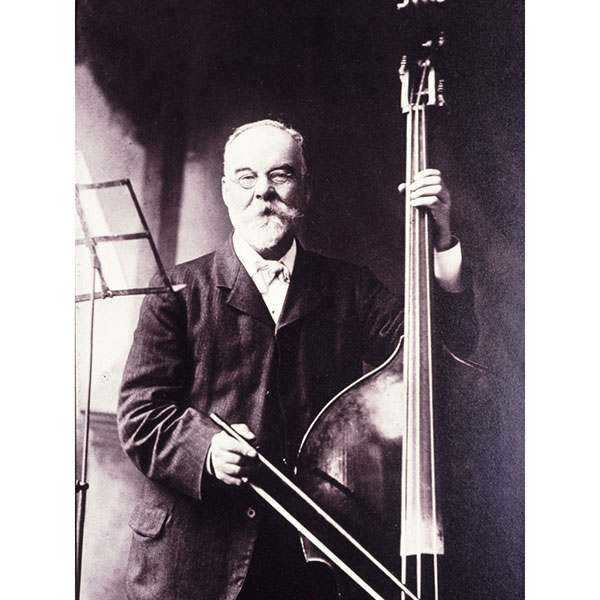

Family members have spoken of how Marshall loved to observe flowers and small creatures, such as lizards, on country walks. They watched him modeling his “beautiful uglies” often incorporating caricatures of friends “as easily as a bird sings.” Marshall was also a talented chorister and musician. He played the double bass and cello in the Lambeth orchestra and could pick up any instrument and play a tune. His daughter, Alice, worked alongside him in the Lambeth Studio for a number of years, and his wife, Helen, inspired one of his few figurines of fashionable ladies.

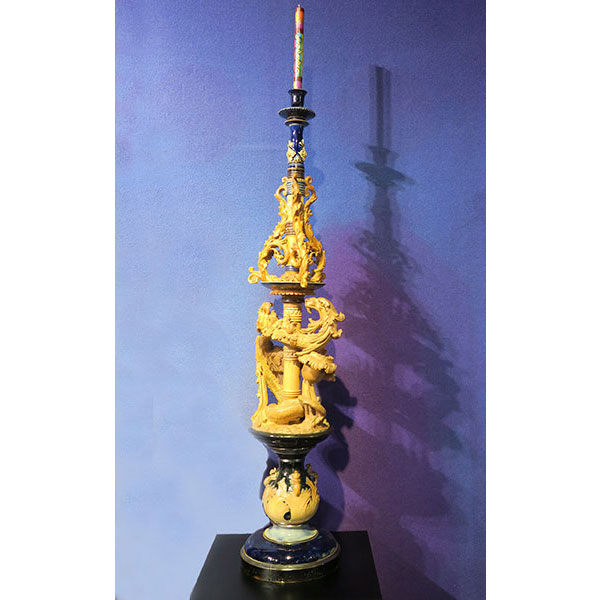

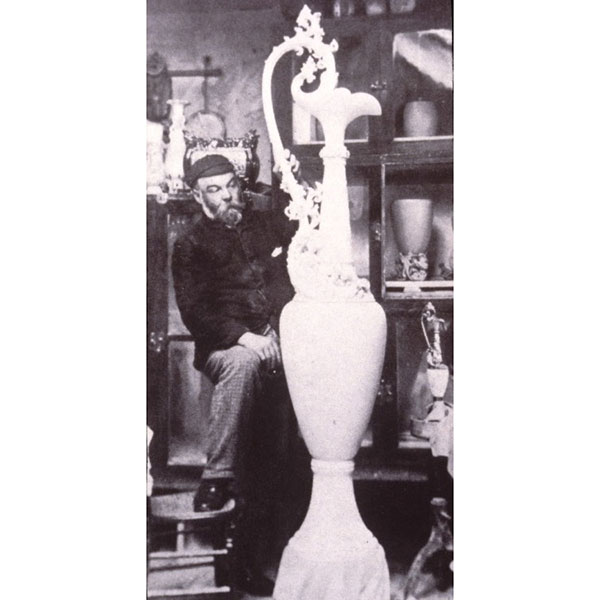

Marshall made some exceptional Doulton stoneware pieces for international exhibitions including a gigantic ewer and stand, over six feet tall, for Chicago in 1893. The large Jabberwock candelabrum at WMODA shows his interest in the prevailing art nouveau aesthetic of the late 19th century which combined well with his sinuous foliate forms and fantastic reptiles. Marshall’s monsters made weird and wonderful garden ornaments in the early 1900s and at the end of his career, he reprised his role as an architectural sculptor when he worked on terracotta caricatures for the Calgary Herald and gargoyles for St. John’s Church in Saskatoon.

Marshall was one of the most imaginative artists ever to work at Doulton’s Lambeth studio. His contemporaries remembered him as a witty, genial guide on studio tours and he was a regular contributor to Doulton’s in-house magazine with his poems and musings. He was much mourned at his death in 1912.

Read more...

Jabberwock detail by M. V. Marshall

Jabberwock by M. V. Marshall

Jabberwock by J. Tenniel

Doulton Jabberwock Candelabrum by M. V. Marshall

Doulton Jabberwock Candelabrum detail by M. V. Marshall

Lambton Worm by J. D. Batten

Mark V. Marshall

Rath by M. V. Marshall

Raths, Borogroves & Toves by J. Tenniel

Humorous Exhibition London 1889

Mark V. Marshall and assistant working on a Rath

Mark V. Marshall and assistants in his Doulton Studio

Doulton Lambeth Vase by M.V. Marshall

Doulton Lambeth Fish by M. V. Marshall

Dinosaur Models Construction c1853 by B. W. Hawkins

Banquet inside an Iguanadon

Royal Doulton Reptiles by M.V. Marshall

Graves Museum T-rex

Larry Williams working on a dinosaur

Larry Williams with a dinosaur

Brown, Westhead & Moore Bear and Cub by M. V. Marshall

Brown, Westhead & Moore Bear and Cub by M. V. Marshall

Martin Brothers Face Jug

Doulton Face Jug by M. V. Marshall

Doulton Face Jug profile by M. V. Marshall

Brown, Westhead & Moore stick stand M. V. Marshall

Doulton Mock Turtle by M. V. Marshall

Doulton Cheshire Cat Paperweight by M. V. Marshall

Doulton Bill Lizard by M. V. Marshall

Bill Lizard by J. Tenniel

Doulton Chess Knight by M. V. Marshall

Chess Knight by M. V. Marshall

Knight on Poker by J. Tenniel

Waning of Honeymoon by M. V. Marshall

Waning of Honeymoon by M. V. Marshall

Waning of Honeymoon by M. V. Marshall

White Rabbit by J. Tenniel

Rabbits detail by Walter Potter

Rabbit and Hedgehog

Beautiful Ugly by M. V. Marshall

Doulton Fabulous Fish by M. V. Marshall

Doulton Puffer Fish by M. V. Marshall

Doulton Fish by M. V. Marshall

Doulton Reptile Vase by M. V. Marshall

Doulton Albert Medal Vase detail by M. V. Marshall

Whist Booby by M.V. Marshall

Pair of Art Union Ewers by M.V. Marshall

Bear Cruet Set by M.V. Marshall

Jardiniere by M. V. Marshall

Jardiniere detail by M. V. Marshall

Chicago Ewer by M. V. Marshall

Gargoyle St John’s Saskatoon

Gargoyle St John’s Saskatoon

Calgary Herald Terracotta Ornament M. V. Marshall

Calgary Herald Terracotta Ornament M. V. Marshall

Calgary Herald Terracotta Ornament M. V. Marshall

Calgary Herald Terracotta Ornament M. V. Marshall

Doulton garden seat by Mark V. Marshall

Umbrella Stand by M. V. Marshall

Beasts by M. V. Marshall

Mark V. Marshall

Ages of Fashion by M. V. Marshall