The new Fantastique exhibit has a ‘thunder’ of dragons on display to use the collective term. There are Eastern and Western dragons plus many other hybrid serpentine monsters from the mythologies of the world, including Wyverns and the mystical Ouroborous.

Chinese Dragons

The five-clawed Chinese dragon was a spiritual and cultural symbol of the emperor’s imperial power and he sat on the dragon throne. The dragon is one of the twelve Chinese zodiac signs and it is deeply ingrained in cultural traditions, including the New Year dragon dances. Outstanding people are often compared to a dragon epitomizing strength, prosperity and good luck. There are two color variations of the Imperial Great Dragon modeled by Francisco Polope for Lladró of Spain featured in Fantastique.

Chinese dragons embody potent and auspicious powers, particularly control over water and weather. Destructive typhoons and tidal waves were said to be caused by a mortal upsetting a malevolent dragon. The Chinese dragon, also known as a Long, is described as having the horns of a deer, the head of a crocodile with demon’s eyes, the body of a serpent covered with fish scales, and the feet of a tiger with eagle claws. They are rarely depicted with wings as their ability to fly among the clouds is mystical.

In popular Chinese religion, the Dragon God is the dispenser of rain. There are four major Dragon Kings representing the Four Seas and Chinese villages close to rivers and seas had temples dedicated to their local Dragon King. The largest Wedgwood Fairyland Lustre vase ever made depicts the Dragon King as envisioned by Daisy Makeig Jones with a mixture of Chinese folklore and her own fanciful dreamland. Her Dragon King guards the shimmering pearl which controls the tides and he causes earthquakes or storms if people come too close. Interestingly Daisy’s Dragon King has large wings and four claws and is accompanied by a smaller wingless dragon with a victim in its jaws. Dragons are also a feature of Daisy’s Ordinary Lustre patterns on a powder blue ground and the motifs used include a Celestial Dragon, a Dragon of Mountains and Marshes, a Cruel Dragon and a Coiling Dragon.

Japanese Dragons

The Japanese dragon, known as a Ryu, originated from China but unlike the Long it has three claws and does not fly very often. It is the demon of the storm and one of the four creatures from the heavens of mythology along with the phoenix, the turtle and the tiger. Oriental dragon motifs had entered the lexicon of European porcelain factories in the 18th century as artists strove to emulate blue and white Chinese porcelain. However, the vogue for Chinoiserie gave way to a wave of Japonism when Western trade with Japan opened up in the second half of the 19th century after more than two centuries of seclusion. In the words of the pioneering Victorian photographer John Thomson who traveled around Asia, “'the Western nations have woken the old dragon from the sleep of Asia”.

The arts and crafts of Japan were a profound influence on European designers following Japan’s exhibits at the World’s Fairs of the 1860s and 70s. The vogue for all things Japanese was later satirized in Gilbert & Sullivan’s the comic opera The Mikado. Japanese porcelain Dragonware inspired several British potters, including Christopher Dresser, the first European designer commissioned to study in Japan. In the 1880s, the Royal Worcester factory introduced ivory porcelain wares with gilded dragons in high relief forming elaborate handles.

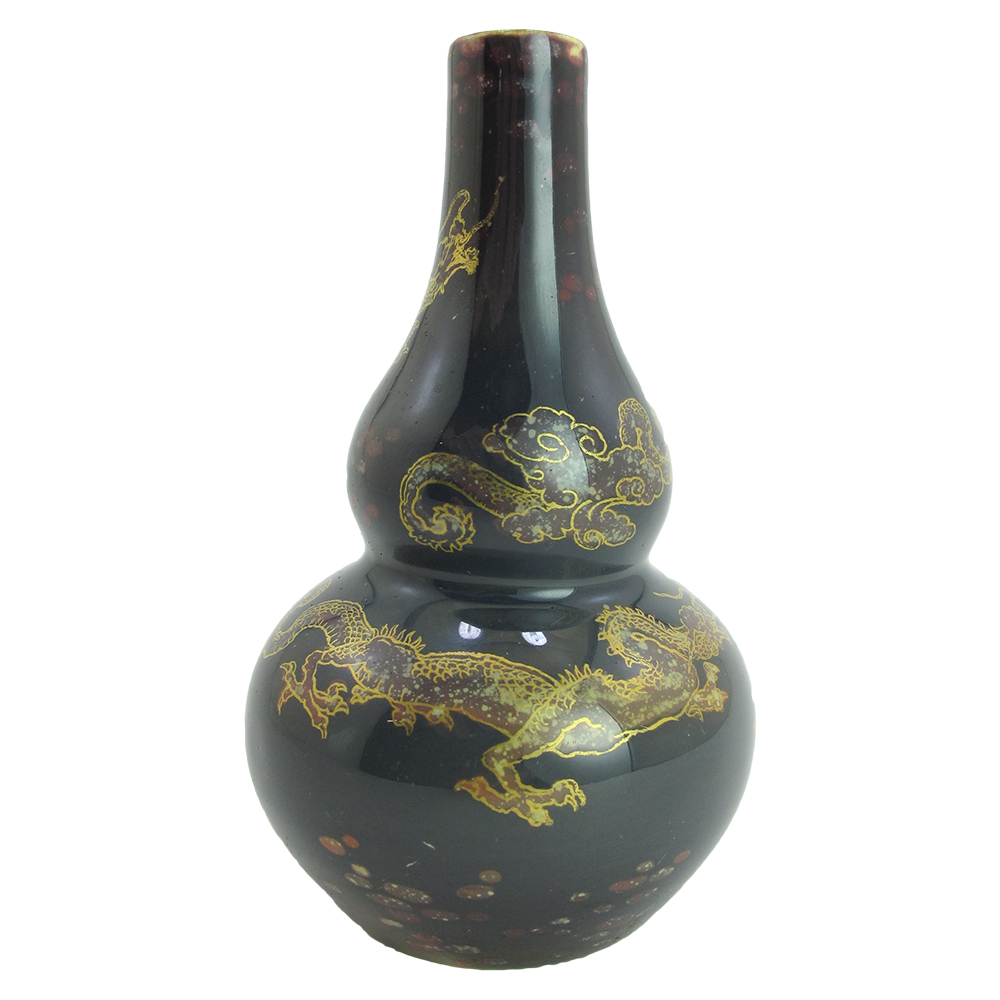

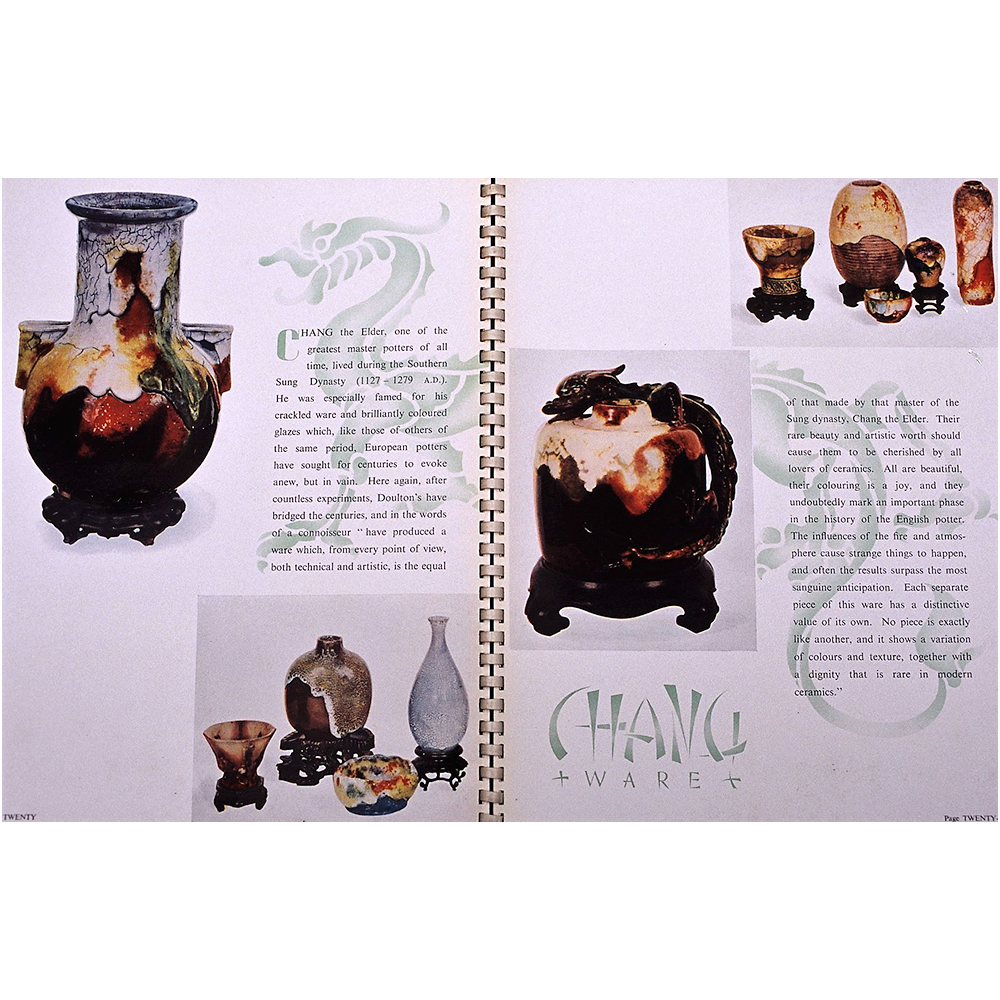

Charles J. Noke, who trained at the Worcester factory before joining Doulton’s of Burslem in 1889, brought this decorative style with him and created a collection of Vellum table centers and vases with dragon embellishments for the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893. Noke’s fascination for Oriental ceramics also led to his famous Sung and Chang wares from the 1920s, which often incorporated exotic dragons. His painted Sung ware dragons are reminiscent of Japanese cloisonné enamels from the Meiji period while his writhing sculptural Chang dragons appear to be derived from molded bronze forms, which were also imported to the West.

Gargoyles & Dragons

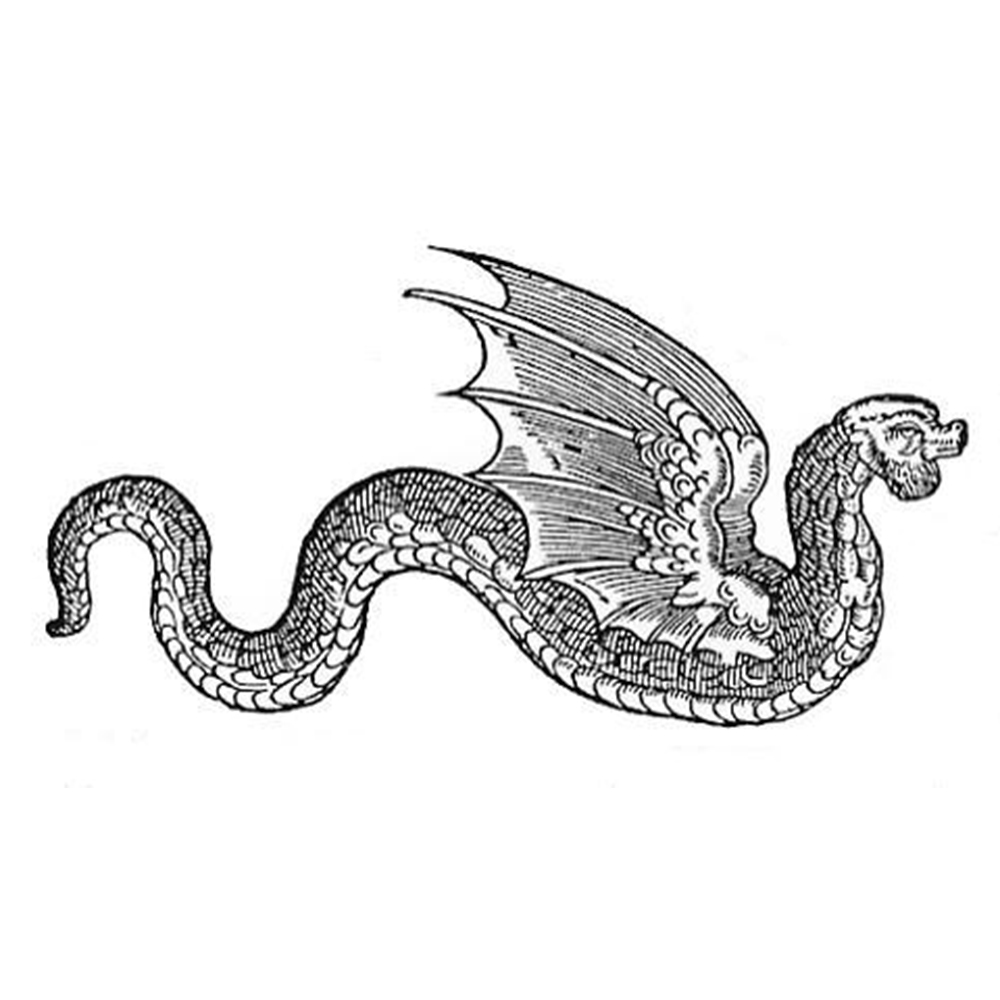

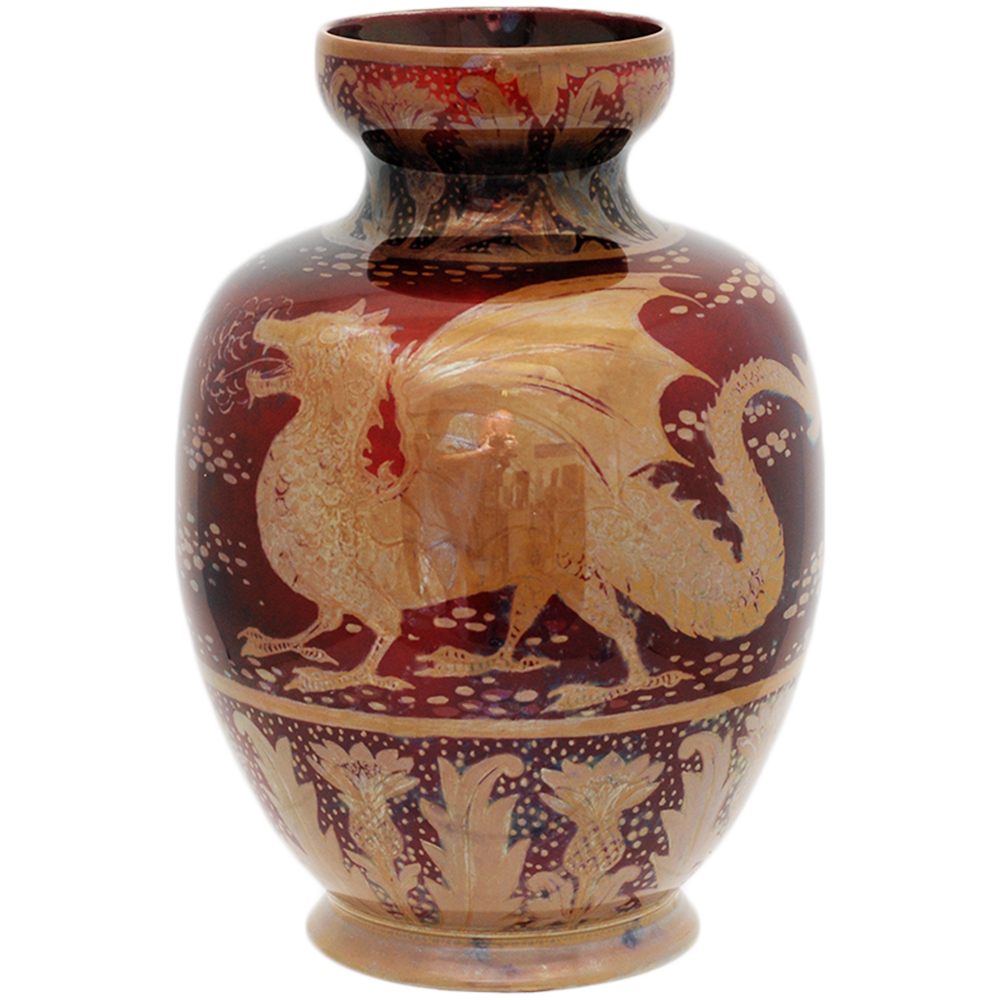

The sinuous forms of dragons were assimilated into the flowing designs of the art nouveau era along with other reptilian creatures. A taste for the grotesque developed during the medieval revival of the 19th century and gargoyles derived from Gothic architecture introduced even more fantastic elements to ceramic designs. Mark V. Marshall at Doulton’s Lambeth Studio excelled in weird and wonderful creatures wrapped around salt-glazed stoneware vases. Before becoming a ceramic designer, Marshall worked for the stone carvers Farmer & Brindley, who provided ornaments for churches and public buildings. In slack times, he also produced designs for the Martin Brothers potters who shared his taste for the bizarre and monstrous. In the late 1890s, Edwin Martin etched designs of dragons and other mythological creatures into stoneware vases. Unlike Eastern dragons, his monsters have wings in common with European imagery. In addition to four-legged dragons, Martin also portrayed the Wyvern, which has two legs, the Amphiptere or winged serpent, and the Ouroborous. This symbol from ancient alchemy depicts a serpentine dragon eating its own tail symbolizing an eternal cycle of destruction and recreation and it can be seen in Fantastique on a ruby lustre tile by William de Morgan.

Dragon-Slayers

In European cultures, the dragon is a menacing winged creature with aggressive connotations, often breathing fire. However, in heraldry the dragon is also symbolic of valor and power. The father of the legendary King Arthur had a dragon symbol on his crest and the Tudor kings adopted the Red Dragon of Wales on their coat of arms. Later, the Tudor queens changed it to gold.

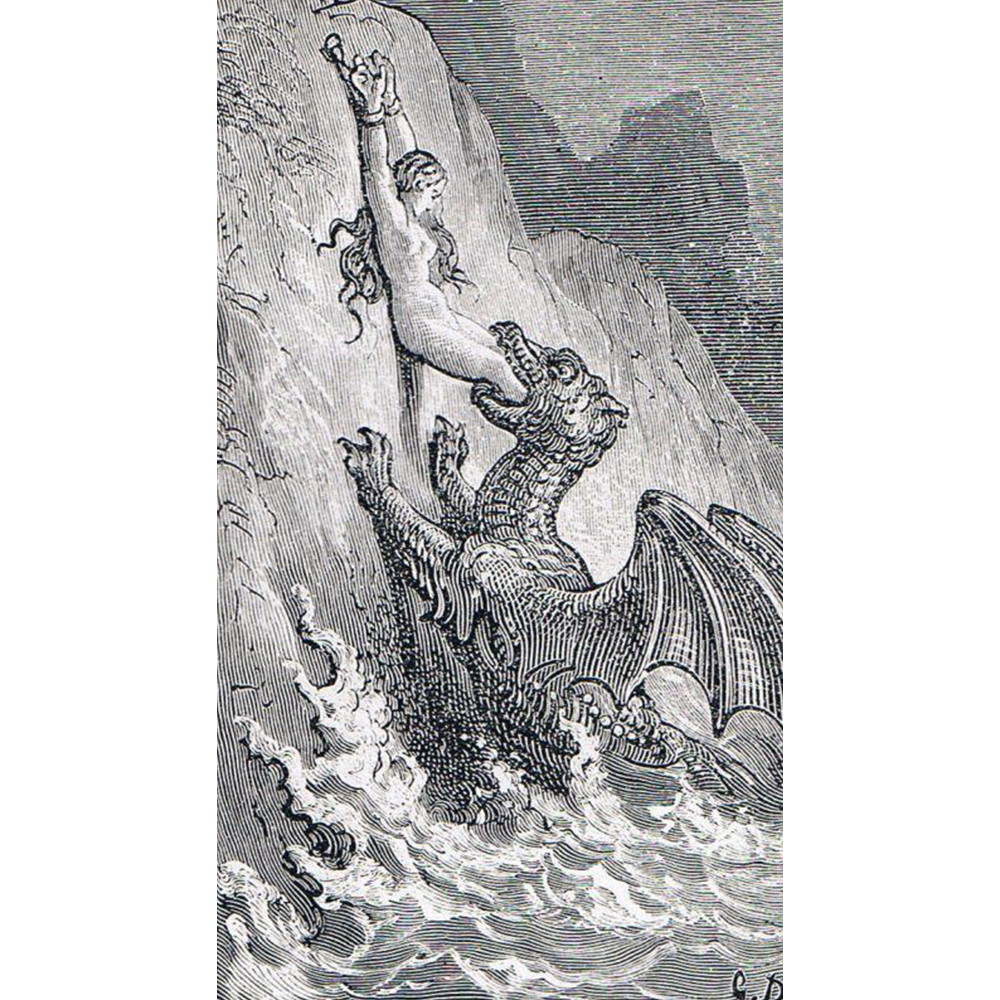

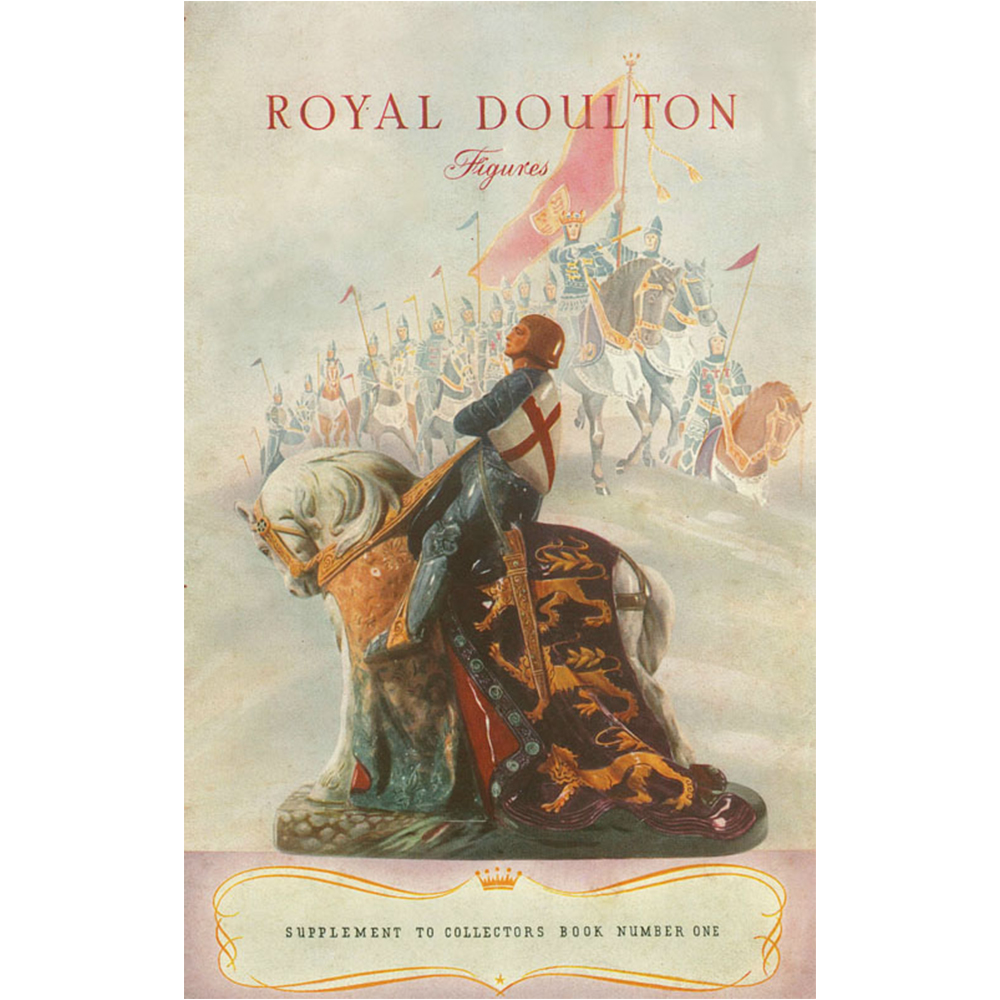

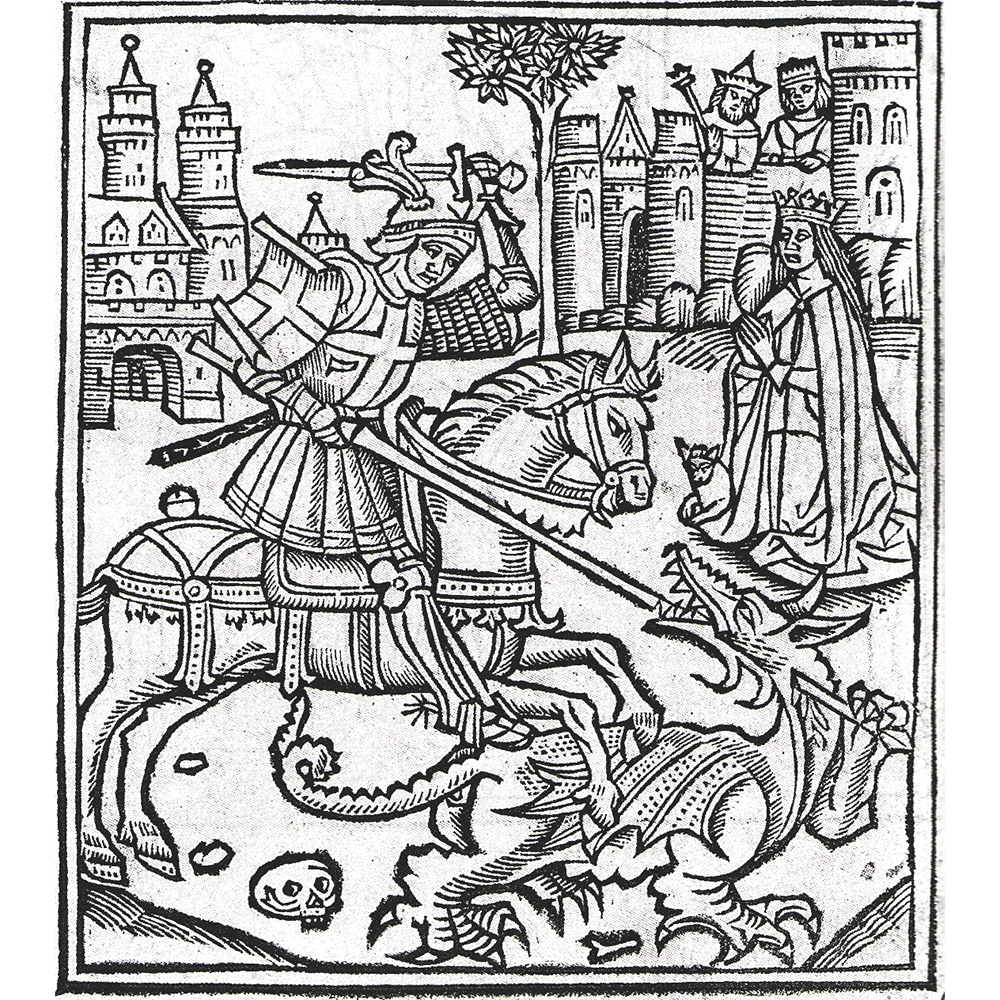

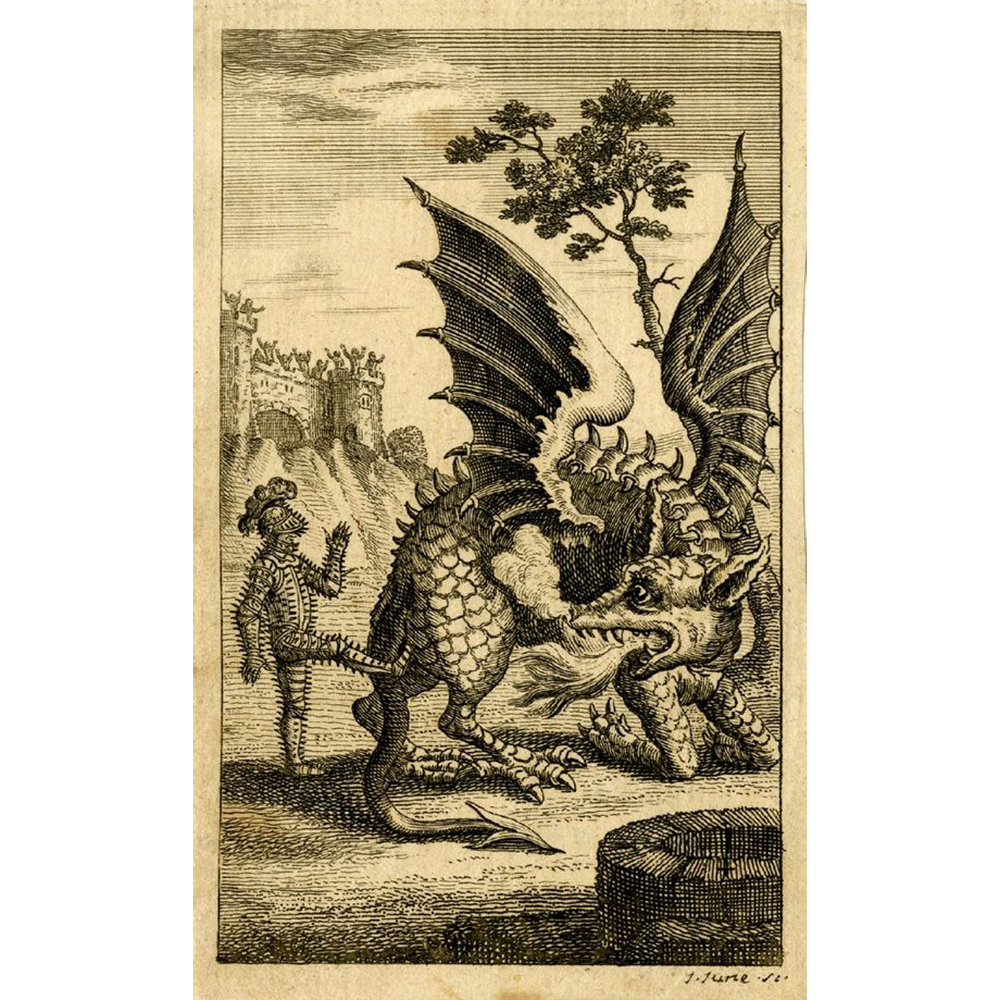

Dragon-slayer myths have a long history in Western culture beginning with the ancient Greek tale of Perseus slaying Cetus, the sea dragon to rescue Andromeda. In Christian legend, St. George, the patron saint of England, killed a dragon which demanded human sacrifices. His heroism inspired medieval tales of chivalry and knights in battle. Over the centuries, depictions of the slain dragon range from crocodilians to reptilian creatures to the winged, fire-breathing monster of Western lore. Several figurative studies of St. George and the Dragon were issued in Royal Doulton’s HN collection during the 20th century and pictorial images of the saint vanquishing the dragon can be seen on luster vases and plaques made by Pilkington for their Royal Lancastrian range.

One of the most curious English dragon-slayer stories inspired Daisy Makeig-Jones. The comic legend of the Wantley Dragon was first recounted in a ballad of 1685 and enjoyed widespread popularity as a burlesque opera and later a Christmas book. The story tells how a Yorkshire knight acquired a bespoke suit of spiked Sheffield armor and delivered a fatal kick to a local terrorizing dragon in between bouts of drinking and carousing.

Don’t miss all the fabulous dragons at Fantastique, the latest exhibition at WMODA.

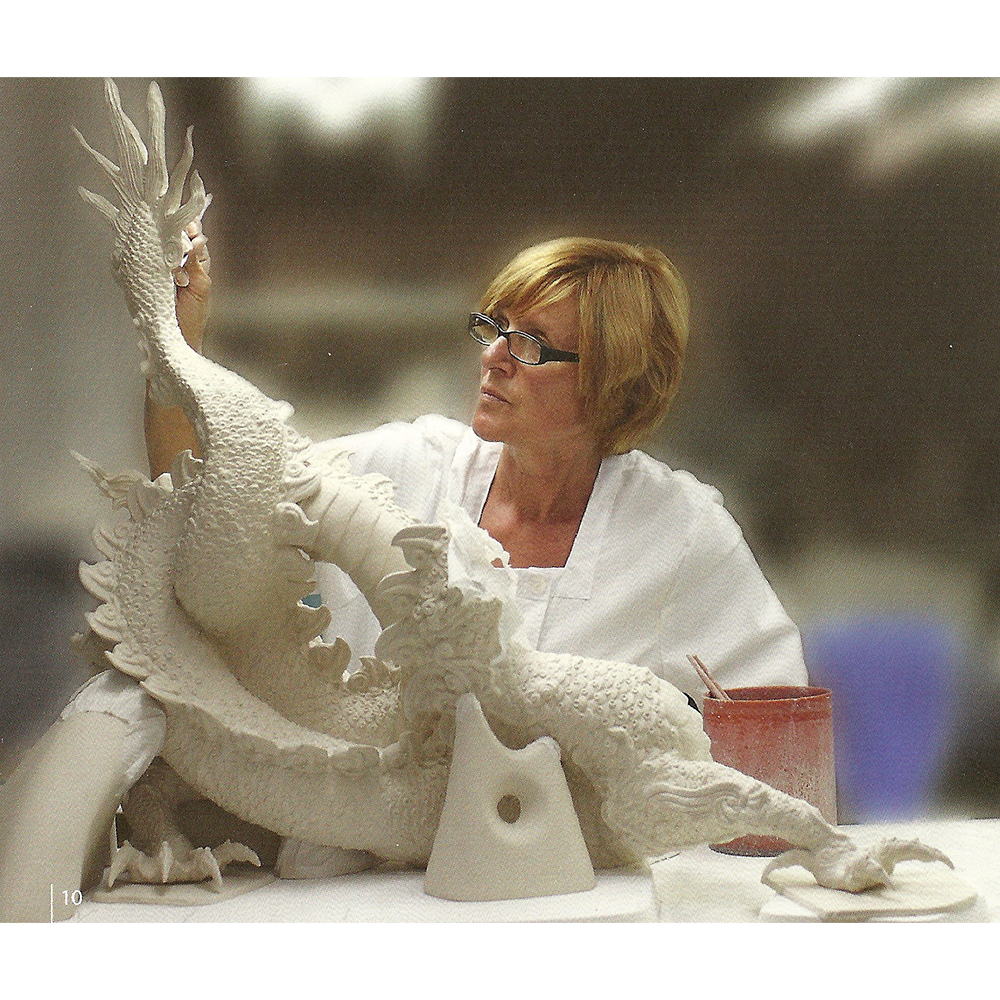

F. Polope with Lladro Dragon

Making the Lladro Dragon

Lladro Great Dragon

Lladro Great Dragon

Royal Doulton Zibo Dragon Clock

Royal Doulton Shenlong Dragon

Wedgwood Dragon King Vase

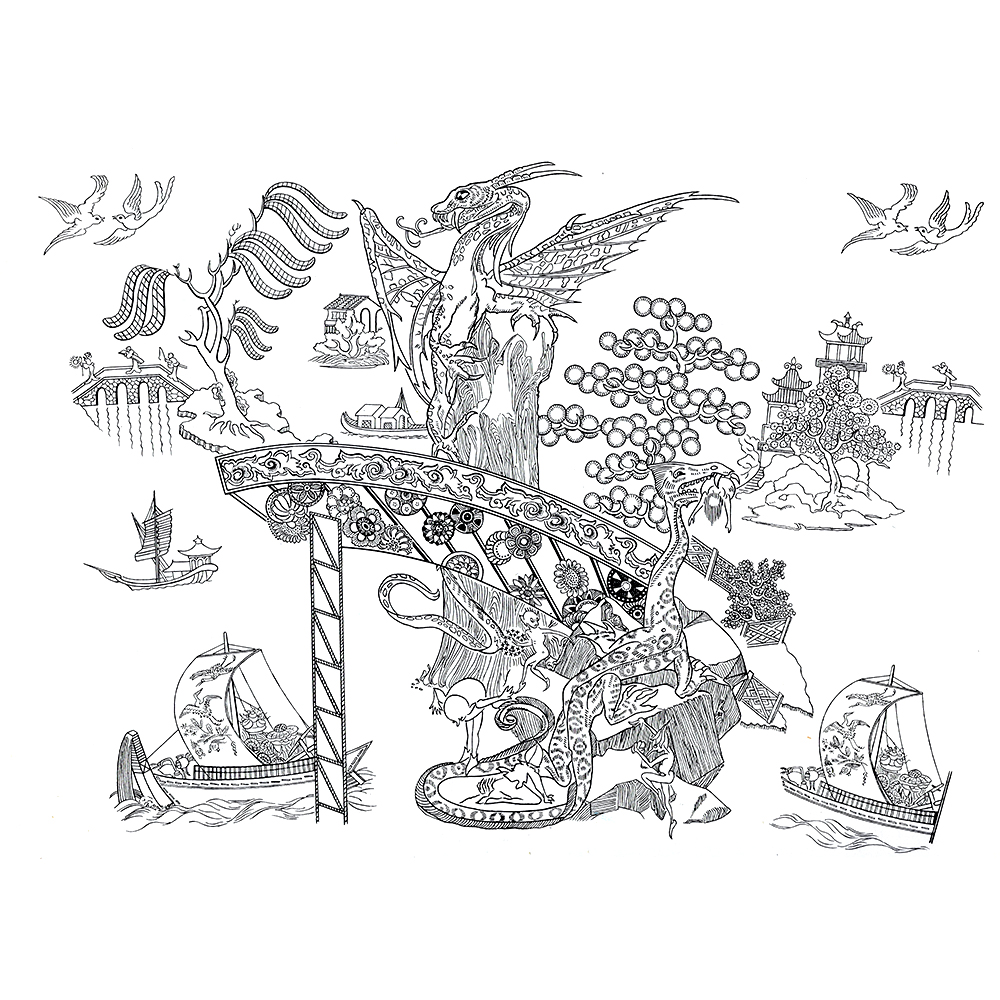

Dragon King Illustration

Wedgwood Temple on a Rock Vase

Wedgwood Temple on a Rock Detail

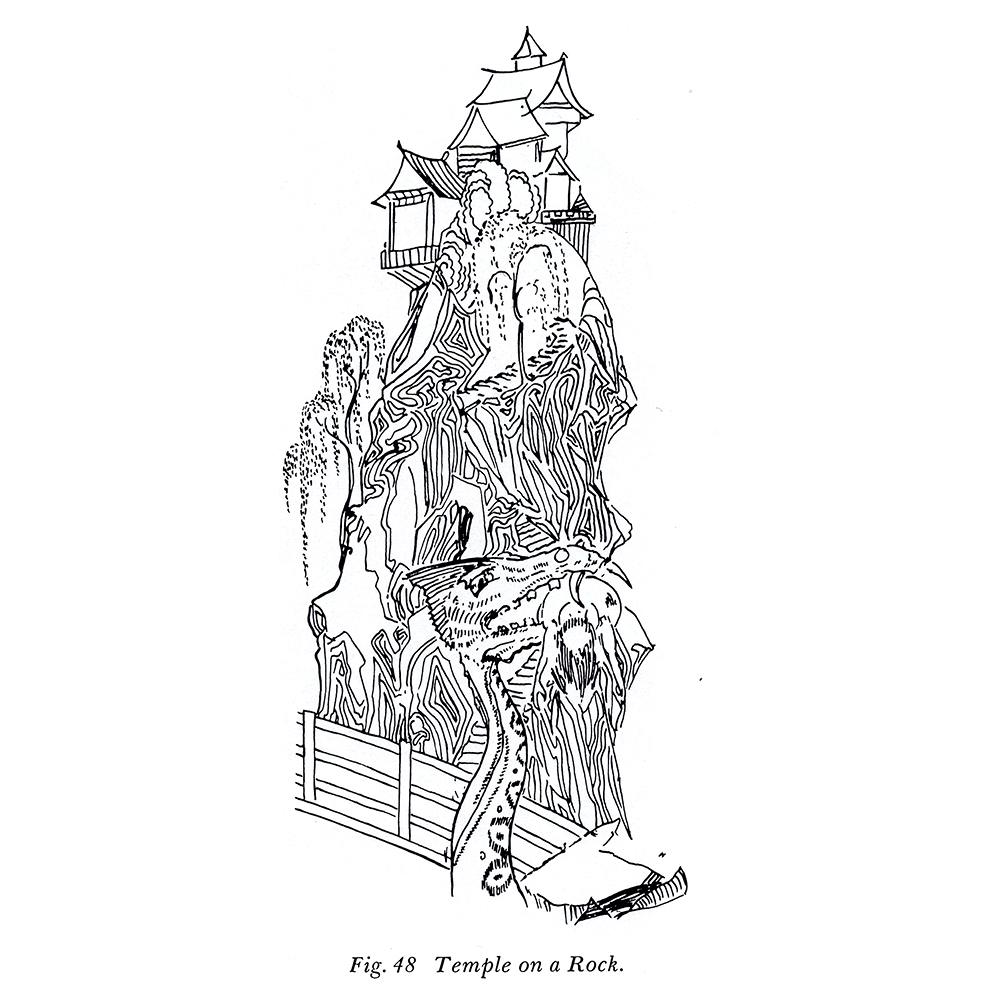

Wedgwood Temple on a Rock Illustration

Wedgwood Dragon Luster Bowl

Wedgwood Dragon Luster Vase

Wedgwood Dragon Luster Dish

Wedgwood Dragon Luster Bowl

Wedgwood Dragon Luster Vase

Wedgwood Dragon Luster

Meiji Bronze Detail

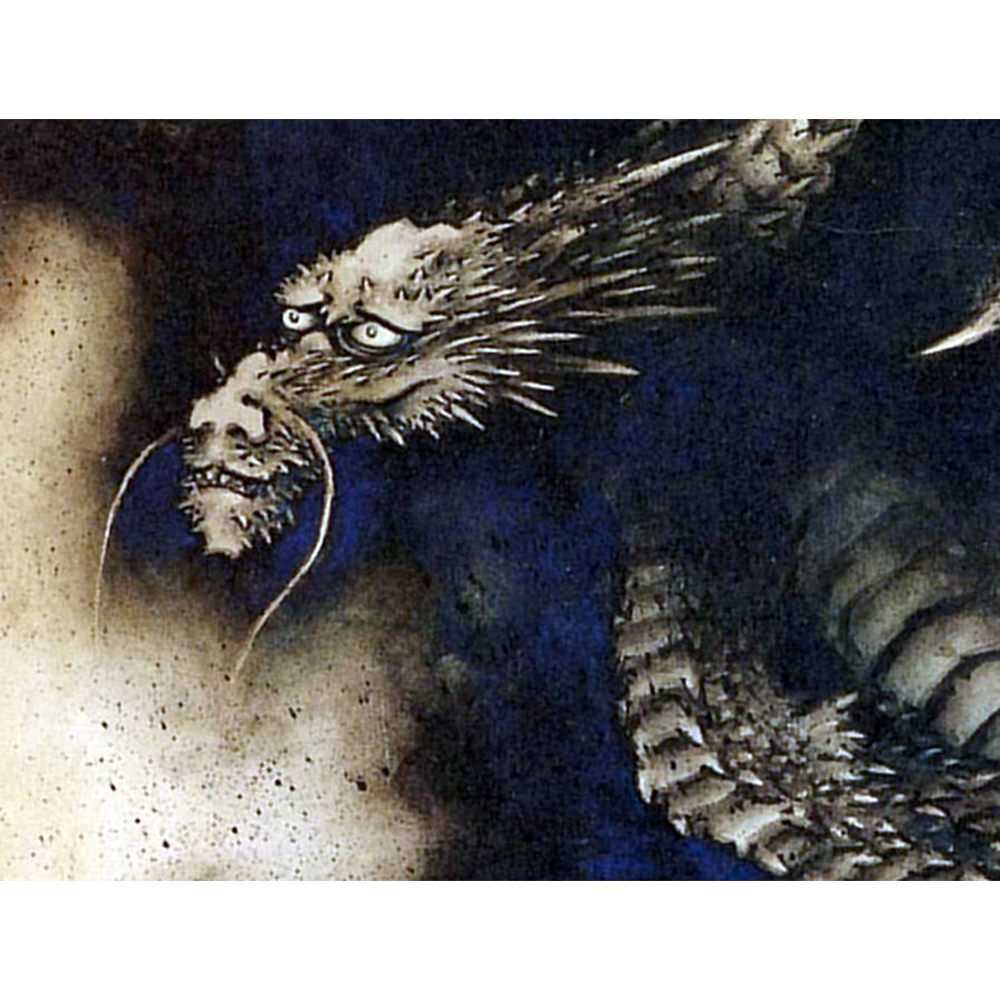

Hokusai Dragon

Royal Doulton Kowloon Vase

Bernard Moore Vase

Doulton Vellum Dragon Ewer

Doulton Chang Dragon

Detail Doulton Vellum Dragon Vase

Doulton Vellum Dragon Vase

Doulton Chang Dragon Vase

Doulton Spanish Ware Ginger Jar

Doulton Chang Dragon Sculpture

Royal Doulton Chang Catalog

Doulton Lambeth Dragon Vase

Doulton Lambeth Dragon Vase

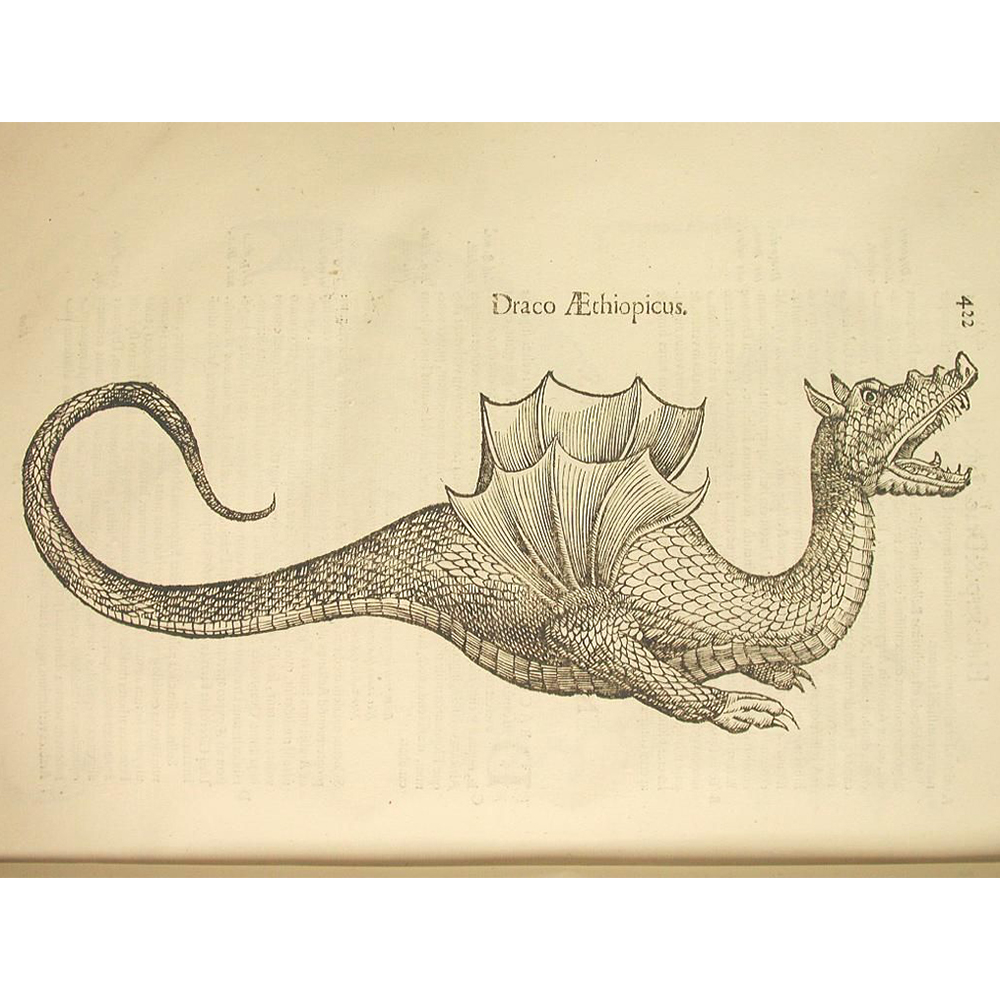

Amphiptere Illustration E. Topsell 1658

Doulton Lambeth Dragon Vase

Andrew Hull Dragon Vase

Dragon Illustrations E. Topsell 1658

Wyvern Plaque

Edward Wilkes Flambe Vase

Doulton Lambeth Chinese Dragon Vase

Wyvern Illustration Aldrovandi

Amphipetre Vase 1903

Dragon Vase 1899

Doulton Garden Ornament

William de Morgan Dragon Tile

Ouroborous Illustration 1625

William de Morgan Tile

Ouroborous Illustration Maeir 1687

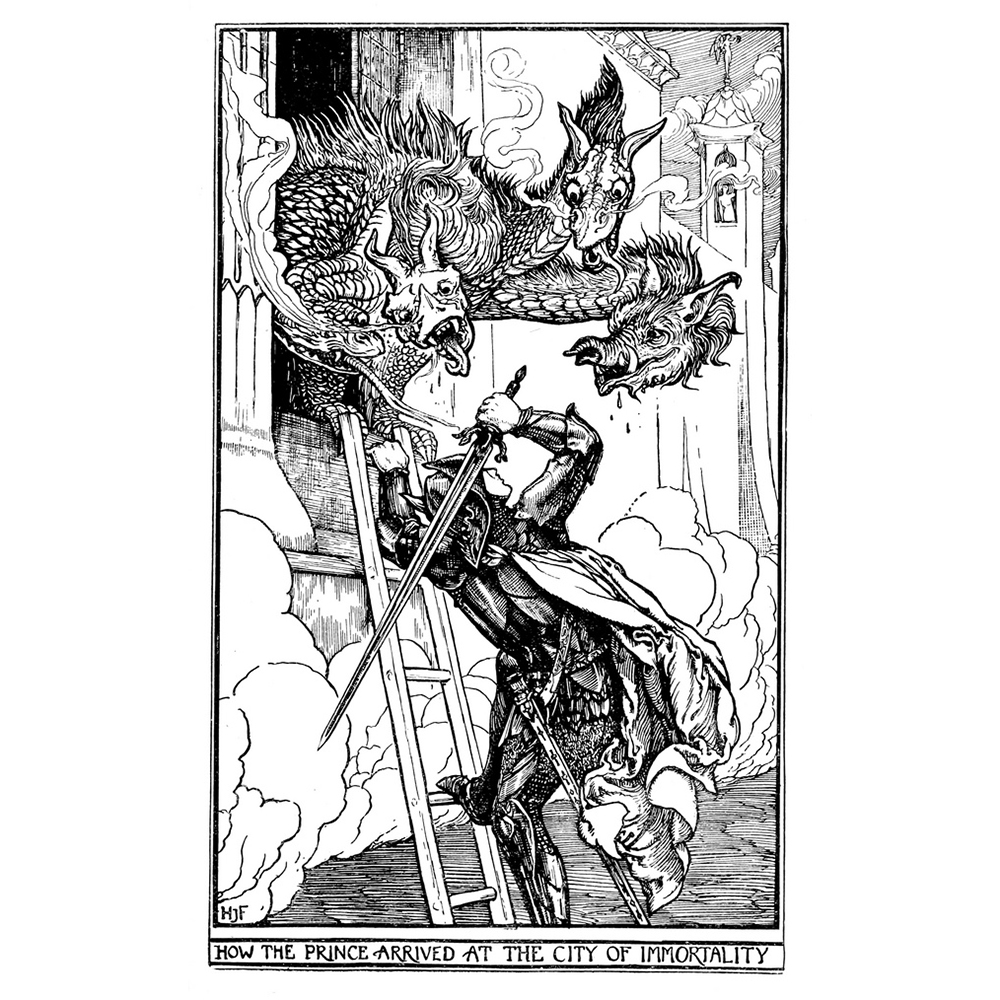

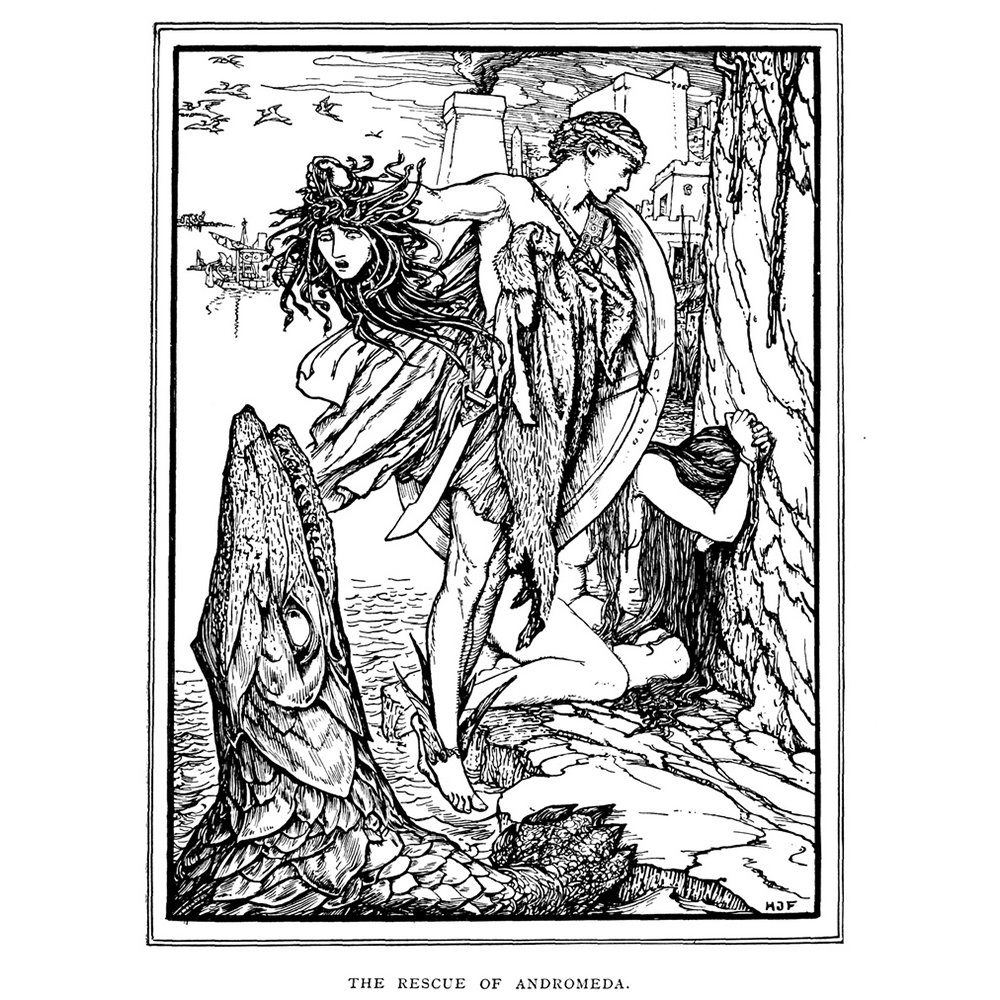

End of the Dragon by H. J. Ford

Perseus by Volkstedt

Dragon Empress illustration

Perseus comes too late Illustration by Dore

Prince City of Immortality Illustration

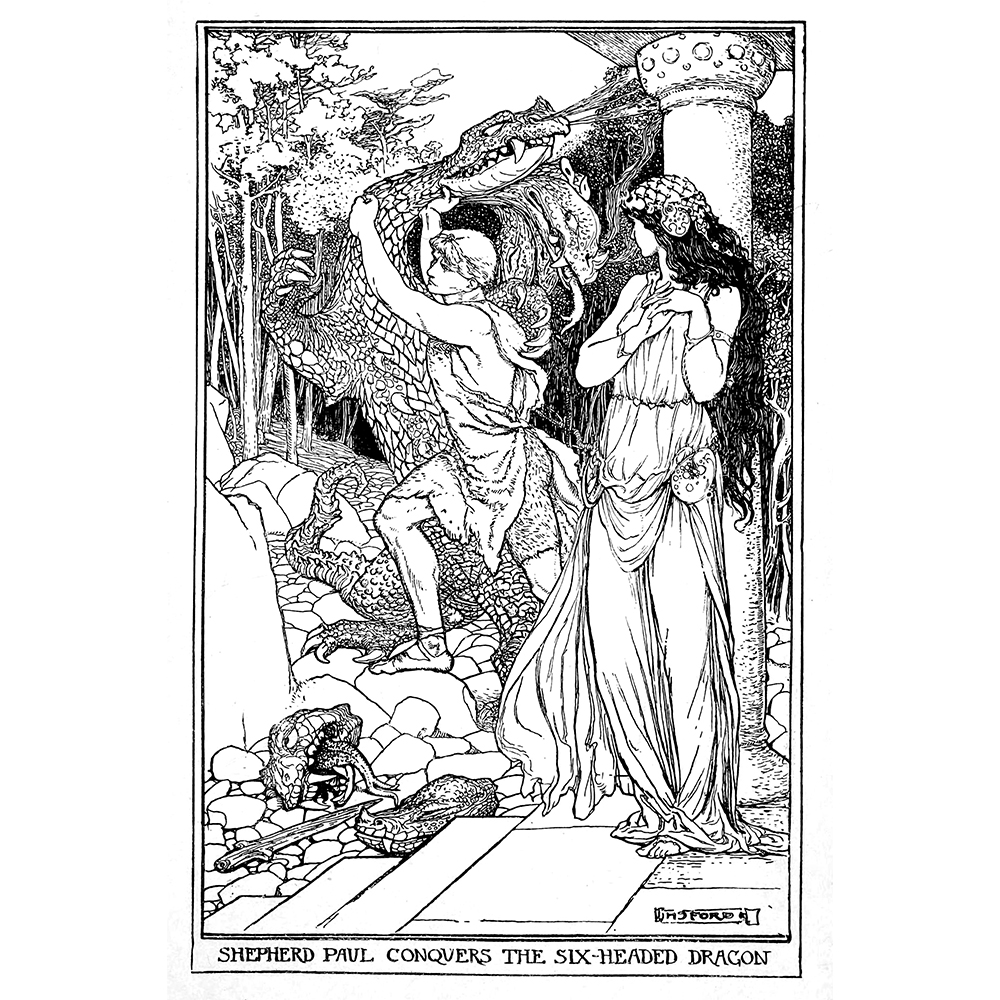

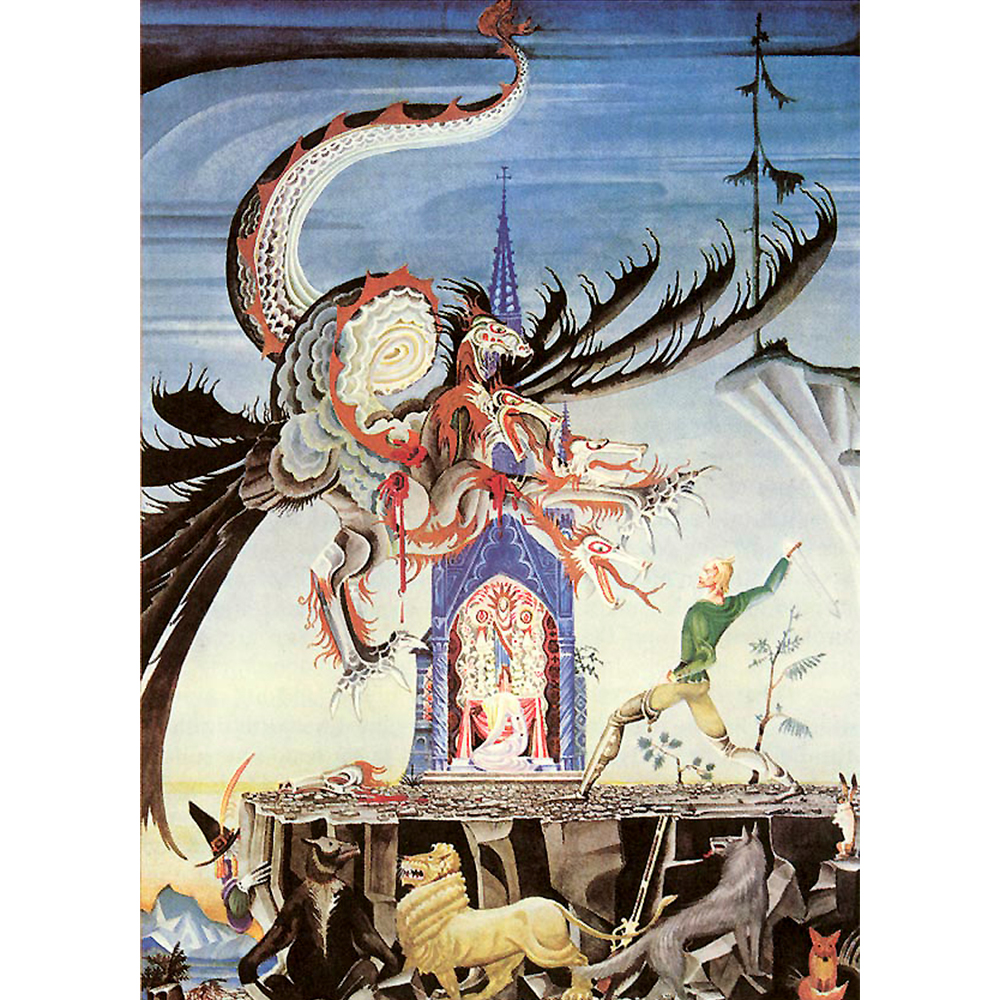

Six Headed Dragon Illustration

Perseus & Andromeda Illustration

Royal Doulton King Arthur

St. George Illustration

Royal Doulton St. George

Royal Doulton Catalog

Royal Doulton St. George

St. George Illustration

St George & Dragon Manuscript

Royal Doulton St. George

St. George Illustration

Seven Headed Dragon by K. Nielsen

Michael Maier

The kiss that gave the victory by H. J. Ford

Dragon Slayer by V. Ellis

Britain Needs You WW1 Recruitment Poster

Wantley Dragon Illustration