By Louise Irvine

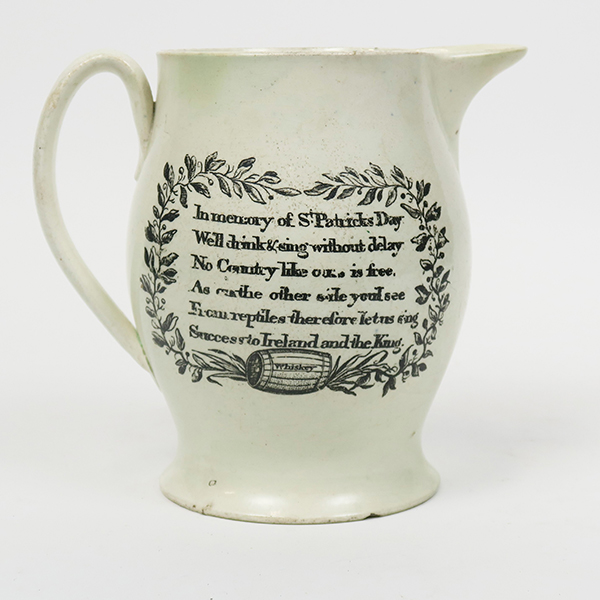

Raise a glass of Guinness and toast St. Patrick on March 17 as we highlight one of the earliest pieces in the collection, a creamware pitcher from the 1790s depicting Ireland’s patron saint. Creamware was developed by the Staffordshire potters in the mid-18th century and was perfect for domestic use. It was also ideal for portraying popular imagery using the new method of transfer printing.

St. Patrick

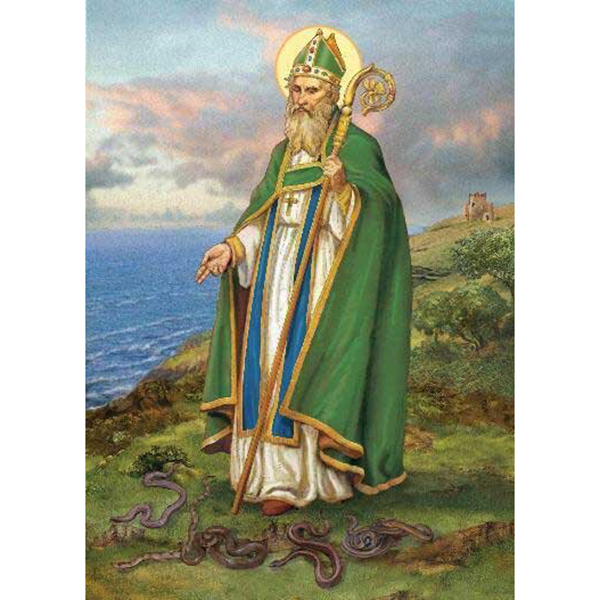

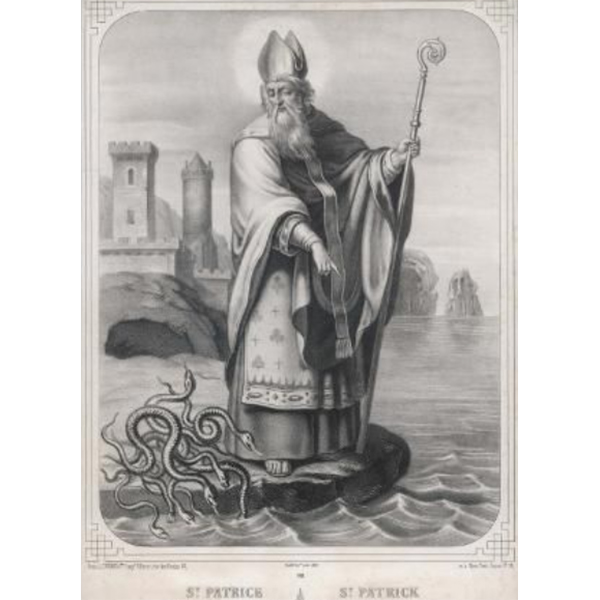

Surprisingly, St. Patrick was not Irish, he was born in Britain during the Roman occupation and enslaved by Irish raiders when he was 16. He escaped and received his religious instruction in England and eventually returned to Ireland as a Christian missionary. St. Patrick is credited with driving the island’s serpents into the sea during one of his sermons and they can be seen slithering away on the creamware pitcher at WMODA. Of course, Ireland never had snakes and banishing the serpents is a metaphor for the eradication of Celtic ideology. Pagans who refused to convert were killed or forced to leave the country.

Shelelaigh

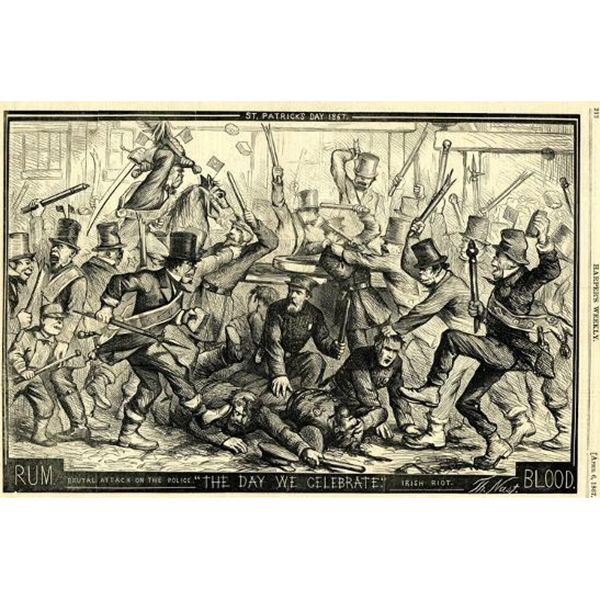

The inscription on the pitcher references two of Ireland’s stereotypical symbols, the shelelaigh and the shamrock. The shillelagh, a more typical spelling, is a stout knotty stick of blackthorn which is used as a walking stick or a weapon. In centuries past, Irish stick fighting was a popular sport and young boys often received shillelaghs as a rite of manhood. Irish gangs settled disputes in violent brawls and this faction fighting is sometimes referred to as Shillelagh Law. In 1867, a St. Patrick’s Day riot broke out in New York and police were attacked with shillelaghs and clubs. Traditional Irish stick fighting has evolved into a martial art and the shillelagh has become synonymous with Irish Gaelic culture at home and abroad.

Shamrock

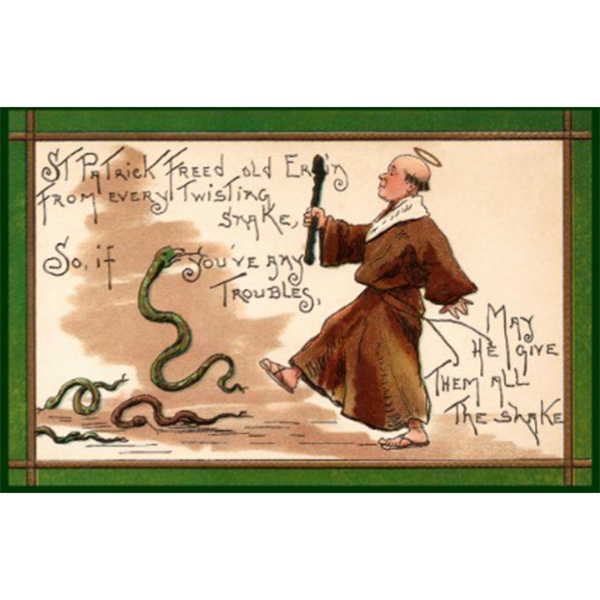

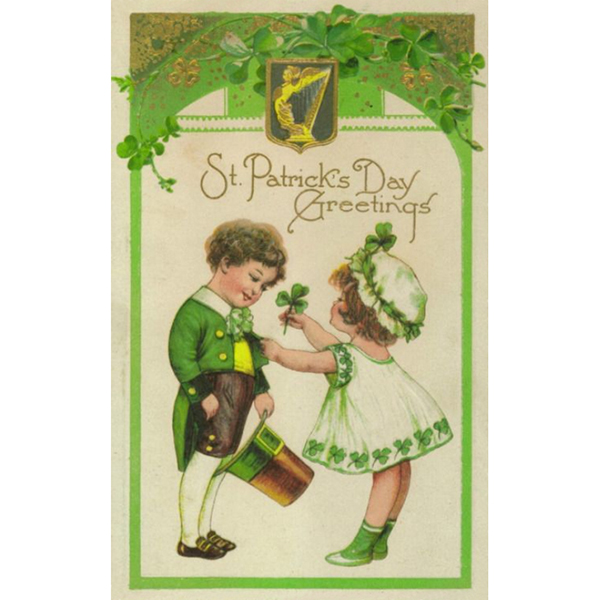

According to Irish legend, St. Patrick used the three-leaf clover as an educational symbol to explain the Holy Trinity to Irish pagans. On the saint’s feast day, churchgoers gathered shamrocks from the fields around their homes as decoration. Discovering a four-leaf clover has been considered lucky ever since the ancient Druid priests claimed they were potent against malevolent spirits. The first of the four leaves is for faith, the second is for hope, the third is for love, and the fourth is for luck. Shamrocks abound in vintage greetings cards for St. Patrick’s Day together with other Irish emblems.

Creamware

English experiments to find a replacement for Chinese export porcelains in the mid-18th century led to the development of creamware, a refined earthenware body with a lead glaze. Thomas Whieldon was one of the pioneering potters in Staffordshire whose partnership with Josiah Wedgwood led to the early success of creamware. Wedgwood continued to perfect the body, which became known as Queen’s ware after a major tableware commission from Queen Charlotte.

Creamware was less expensive than the new soft-paste porcelain produced by English factories and it became a huge commercial success in the domestic and export markets. Wedgwood’s formula was adopted by many other potteries in Staffordshire, as well as in Liverpool and Leeds. Before long, creamware replaced white salt-glazed stoneware and tin-glazed earthenware for sophisticated dining.

Creamware was decorated with hand-painting or transfer-printing which was developed in the mid-18th century. A plethora of popular images appeared on underglaze and overglaze creamware. Factories often outsourced their decoration and offered similar patterns so the attribution of unmarked pieces, such as this St. Patrick pitcher, has always been challenging.

Read about Ireland’s Waterford Crystal

Read about Guinness

St. Patrick Creamware Jug

St. Patrick Creamware Jug

St. Patrick Creamware Jug Detail

St. Patrick Banishing Snakes

St. Patrick Banishing Snakes

St. Patrick Vintage Card

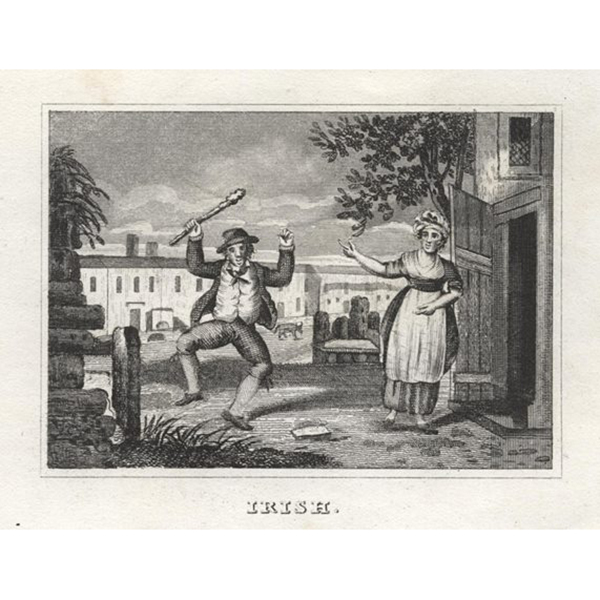

Royal Doulton Irishman

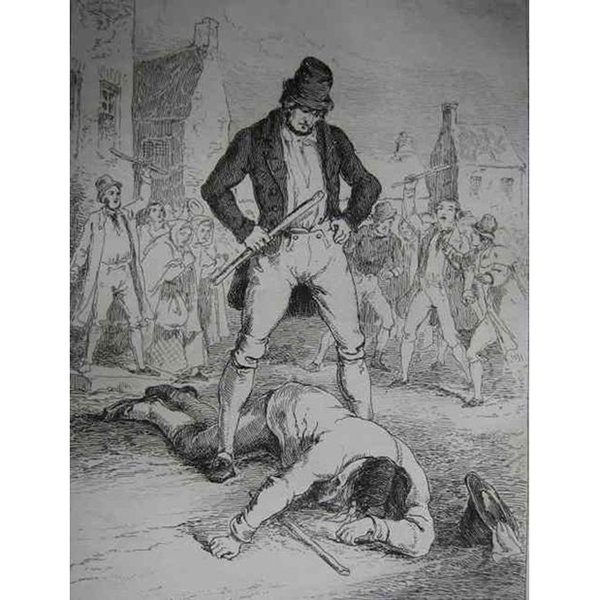

Irishman with Shillelagh

Irish Stick Fighting

Patrick’s Day NY Riot 1867 Thomas Nast

Royal Doulton Prototype Irish Harpist

Vintage St. Patrick's Day Card

Vintage St. Patrick's Day Card

Vintage St. Patrick's Day Card

Vintage St. Patrick's Day Card