By Louise Irvine

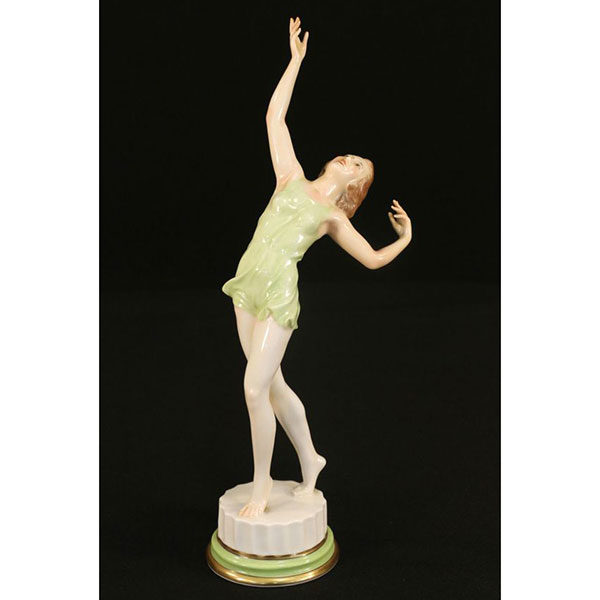

One of the latest WMODA acquisitions is a striking Goldscheider figure of Mary Wigman, the expressionist dancer, who was an iconic star of Weimar German culture. She brought existential dance experiences to the stage in the 1920s with her avant-garde performances and teaching methods. Her influential work has inspired a closer look at some of the pioneering dancers portrayed in European porcelain in the museum’s new Art Deco gallery.

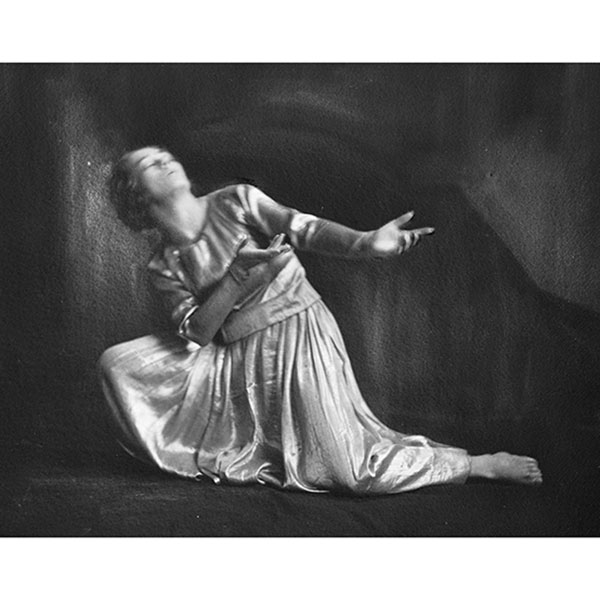

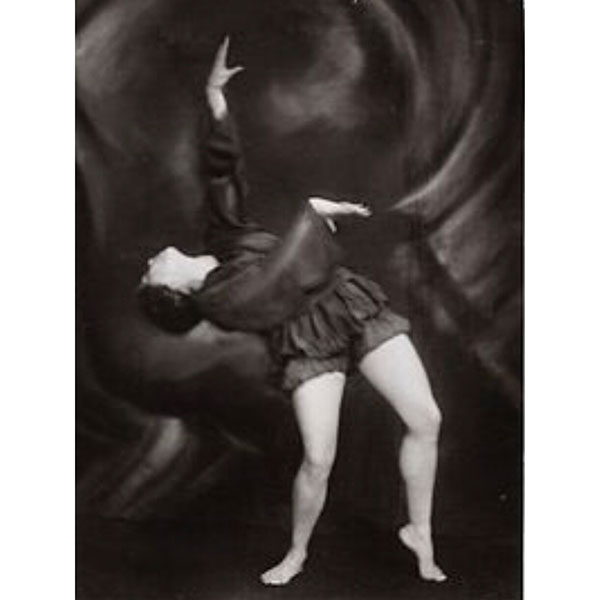

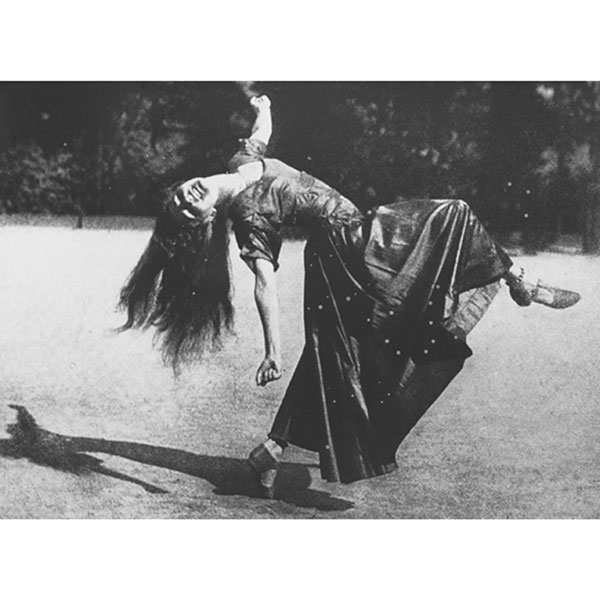

Mary Wigman studied the art of movement at the Rudolf von Laban School for Art and continued as a teacher of his technique until 1919. She believed dance should not be subordinate to music and was often accompanied only by bells, gongs, or drums. Her style was described as “tense, introspective and somber” but always with “an element of radiance, even in her darkest compositions.” She choreographed many solo dances, her most famous being Hexentanz (Witch Dance.)

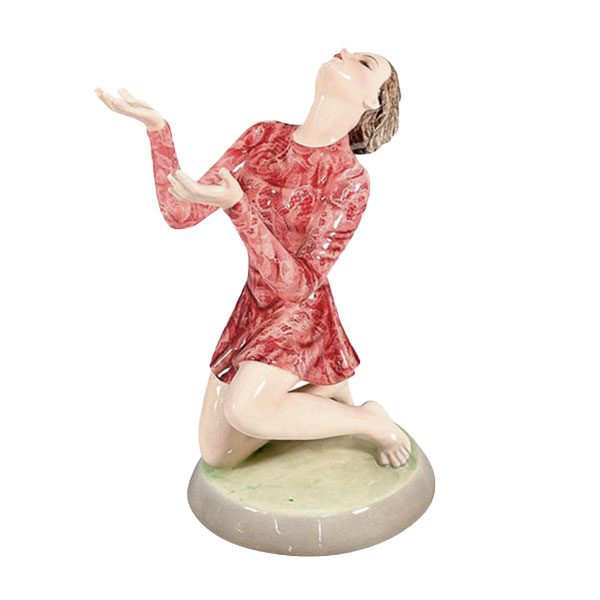

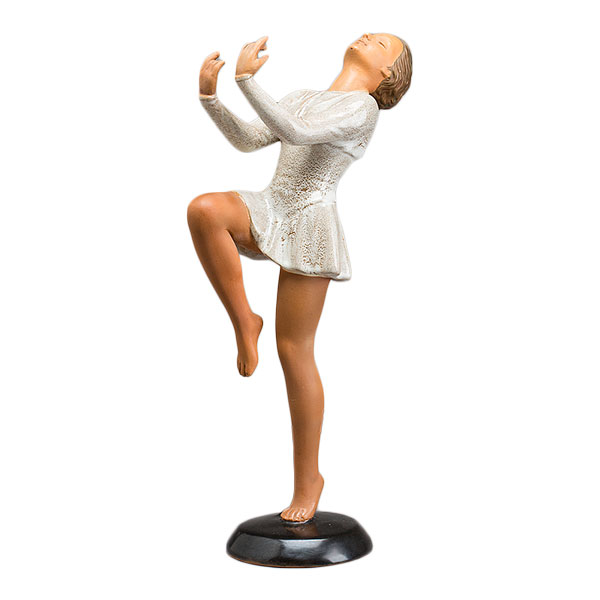

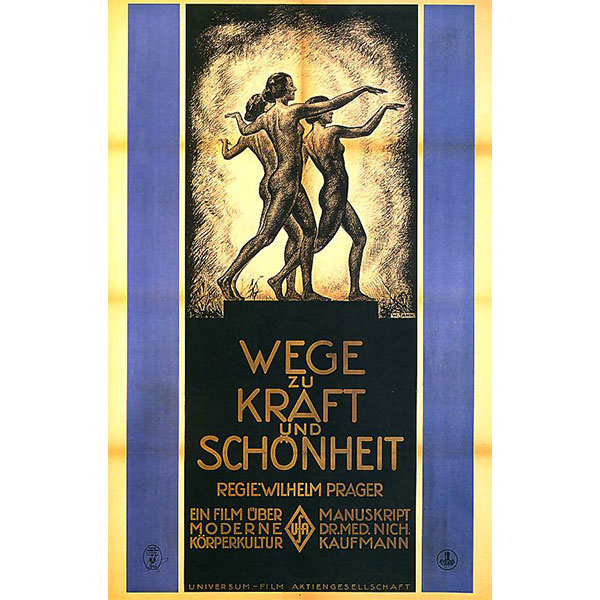

Wigman opened a school of modern dance in Dresden in 1920 and film recordings of her dance group were used in the 1925 cultural silent film Ways to Strength and Beauty. This movie celebrated all forms of dance and exercise to revitalize war-torn Germany. Wigman advocated “Dance is the unification of expression and function, illumined physicality and inspirited form. Without ecstasy no dance! Without form no dance!” Sculptor Josef Lorenzl captured Mary Wigman mid-dance in two evocative figures for Goldscheider.

Wigman and her dancers toured Europe and the United States in the 1930s and many of her former students opened branches of her school throughout Germany. A New York school was started by her protégée, Hanya Holm. Wigman’s most famous male student was Harald Kreutzberg, renowned for his portrayal of Lucifer in Nightsong, and immortalized in porcelain by Waldemar Fritsch for Rosenthal in 1951.

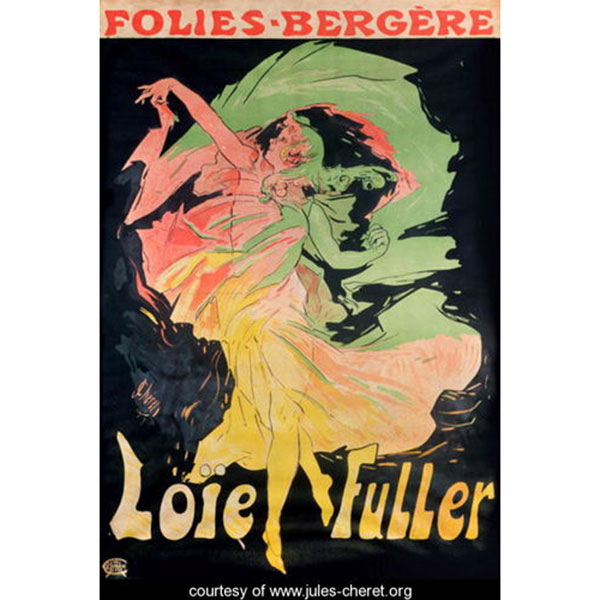

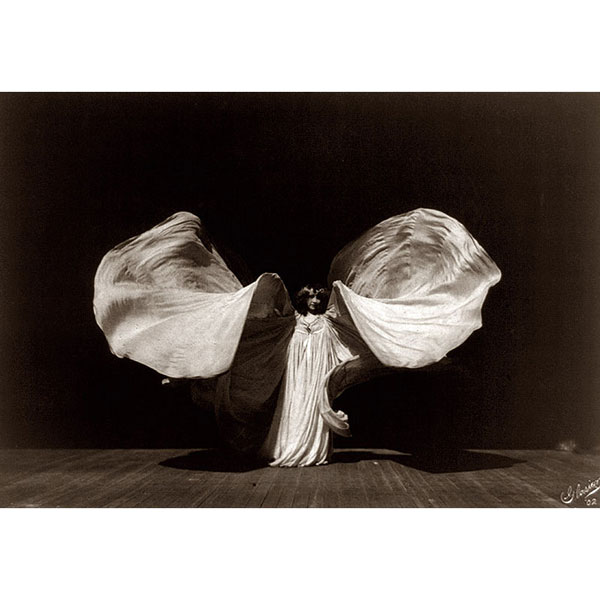

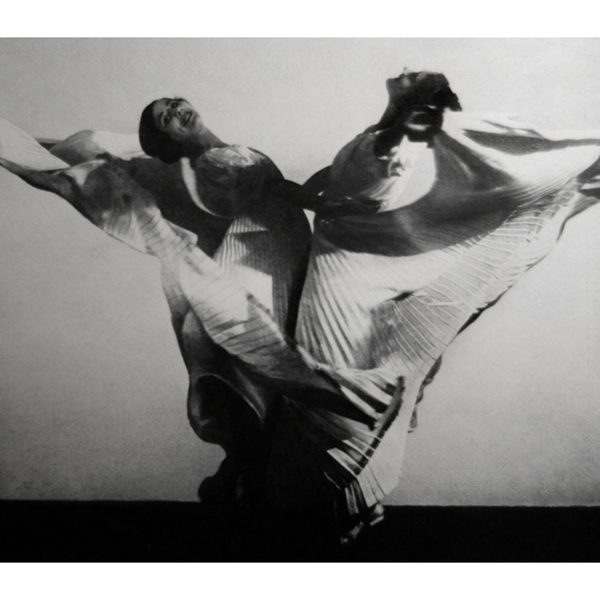

The first experimental dancer represented in the WMODA collection is Loie Fuller, known as the “Electric Fairy,” for her dazzling performances with swirling fabric and cascades of colored light projections on the stage of the Folies Bergère. She used long bamboo poles to extend her arms as she manipulated voluminous lengths of silk fabric in sweeping, serpentine movements. She seemed to transform into a butterfly or a lily and became a blazing symbol of Art Nouveau in Belle Epoque Paris. Her mesmerizing movements were captured in the first silent films and inspired porcelain artists at Sèvres, Meissen and Royal Doulton. Charles Noke’s fabulous Doulton dancer honors “La Loie” and was donated to WMODA by Caroline D’Antonio.

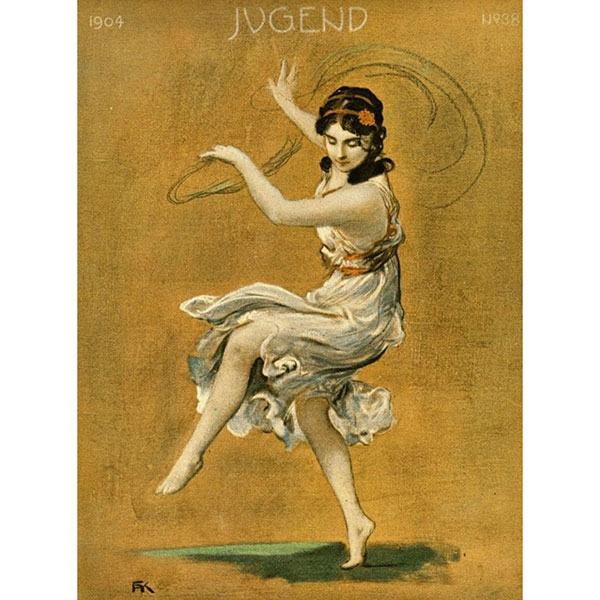

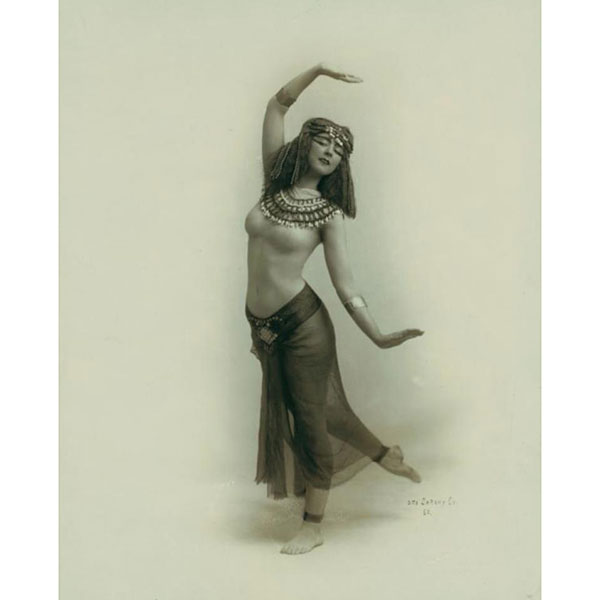

The expressive dance movement began in the early 1900s as a reaction to classical ballet with its conventional forms. Modern dance was improvisational, uninhibited, provocative and revolutionary. Isadora Duncan, a key protagonist, advocated barefoot dancing and took off her ballet pointe shoes arguing, “you do not play the piano with gloves on.” Body culture reform movements went even further expressing themselves with “natural” naked dances.

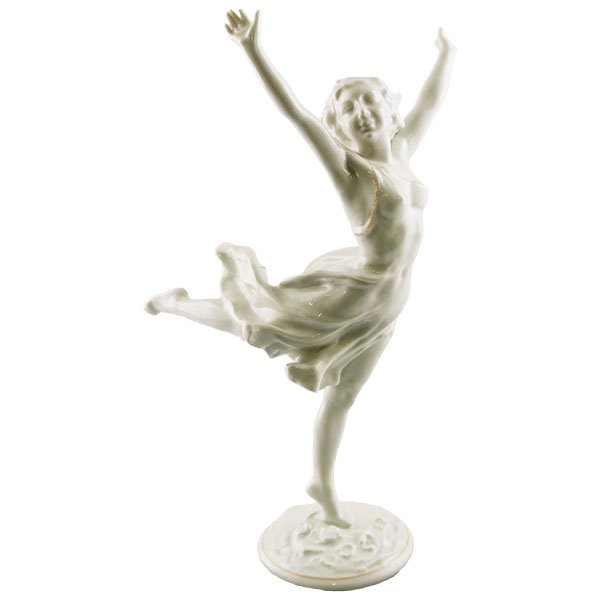

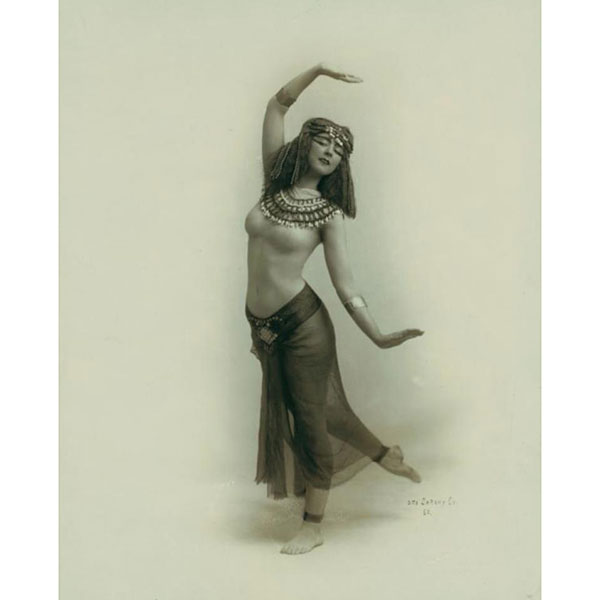

In a quest to unite body, mind and spirit in the art of movement, free dancers sought inspiration from ancient Greek, Egyptian and Indian art. Isadora Duncan famously posed in a classical Greek costume at the Parthenon in Athens. She claimed, “Freedom, spontaneity, revolution is the spirit of my dance.” The same principles applied to her life which was tragically cut short by a freak accident when her long scarf was entangled in the wheel of her car. The Rosenthal, Hutschenreuther and Karl Ens porcelain factories in Germany produced many striking figures of scantily dressed barefoot dancers influenced by Isadora.

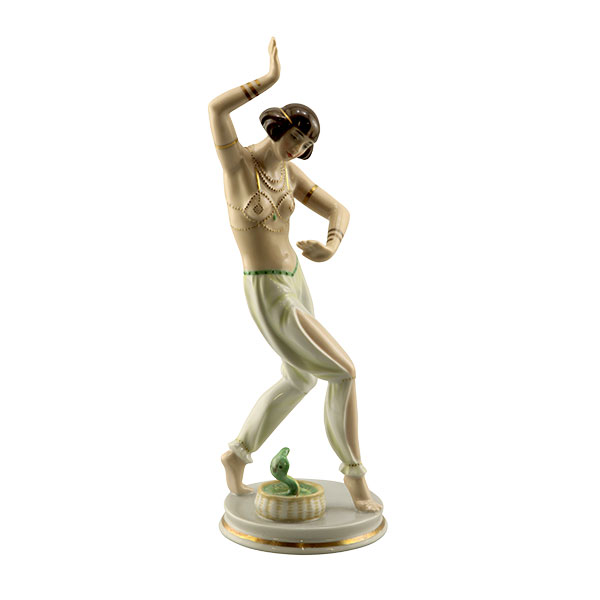

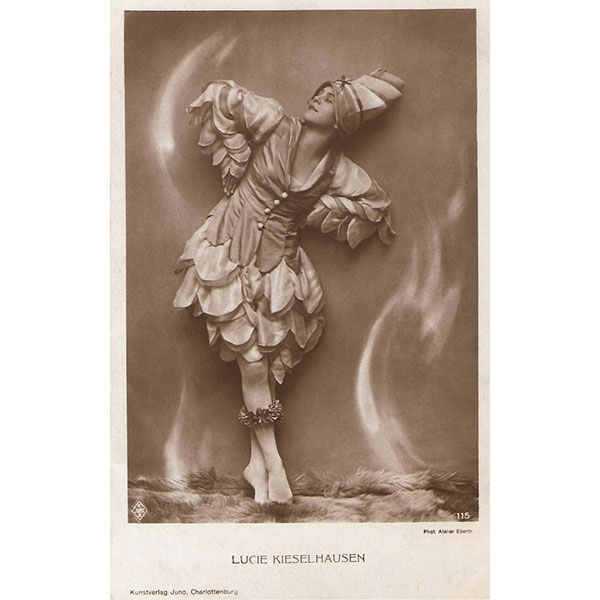

Grete Wiesenthal was the celebrated champion of free dance in Vienna and transformed the waltz into a euphoric solo dance. In 1912, when she debuted in New York, a critic described her as “the high priestess of joy and ecstasy.” The Wiesenthal sisters danced together using expressive spinning movements with waltz rhythms in a unique form of unconventional dance. One of their students, Lucy Kieselhausen, wrote a seductive dance drama called Salambo which sensationalized veil dancing and snake dancing on the stage.

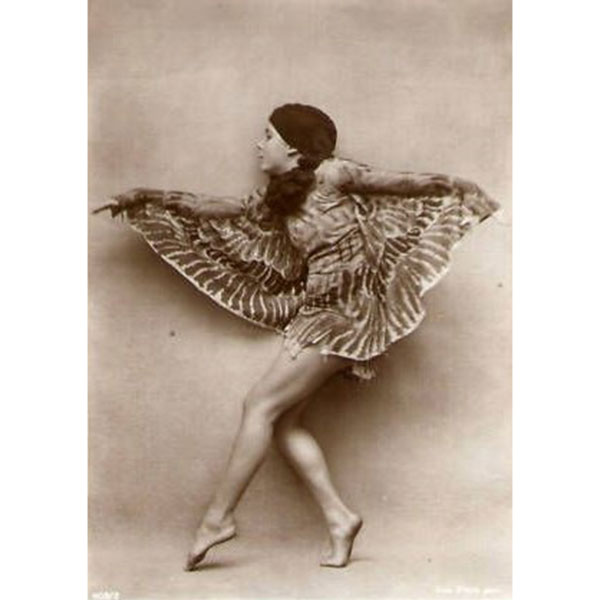

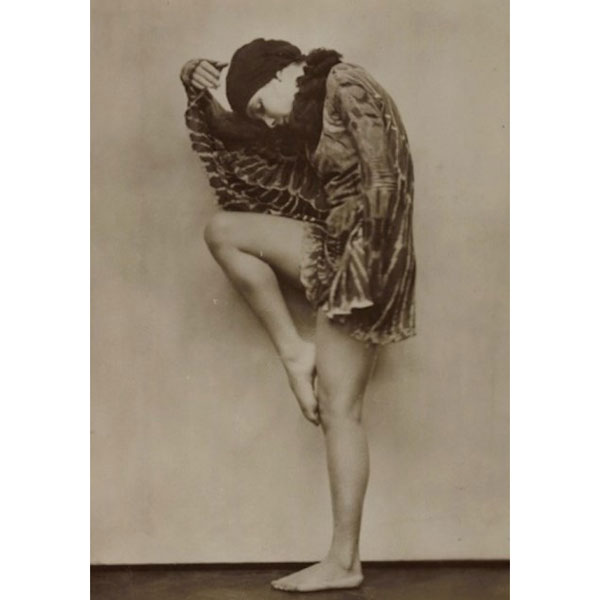

The nubile movements and emotionally charged performances of Niddy Impekoven also caught the imagination of porcelain artists. Her expressionist dances interpreted grotesque artistic dolls which were fashionable with adults in the 1920s. Her famous role as a Captured Bird inspired Goldscheider’s most iconic figure which was produced in four different sizes, two poses and various colors. See them in the Art Deco Gallery at WMODA when the museum reopens.

Read more about modern dance at WMODA

Goldscheider Mary Wigman J. Lorenzl

Goldscheider Mary Wigman J. Lorenzl

Goldscheider Mary Wigman J. Lorenzl

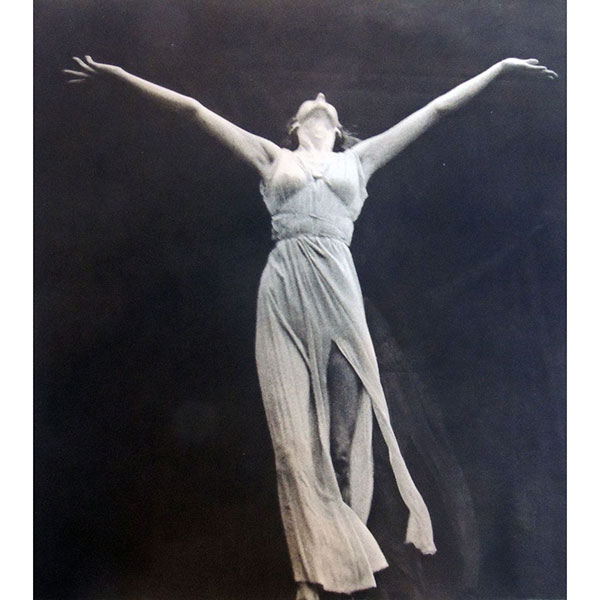

Mary Wigman Merkelbach Studio

Mary Wigman Merkelbach Studio

Ways to Strength and Beauty Documentary

Ways to Strength and Beauty

Rosenthal Nightsong Harald Kreutzberg

Harald Kreutzberg

Rosenthal Nightsong Harald Kreutzberg

Harald Kreutzberg in Nightsong

Royal Doulton Loie Dancing C.J. Noke

Royal Doulton Loie Detail

Folies Bergere Poster

Meissen Loie Fuller T. Eichler

Loie Fuller

Karl Ens Floral Garland Dancer

Karl Ens Nude Dancer

Karl Ens Isadora A. Buschelberger

Karl Ens Isadora Duncan

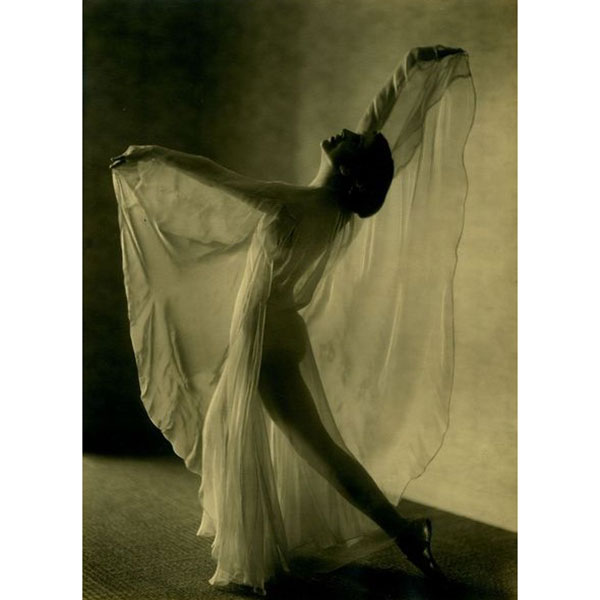

Isadora Duncan Postcard

Isadora Duncan

Rosenthal Dancer

Rosenthal Scherzo

Rosenthal Ionian Dancer

Hutschenreuther Dancer

Passau Dancer

Katzhutte Dancer

Lili Green

Ruth St. Denis

Rosenthal Kaiserwalzer

Grete Wiesenthal

Wiesenthal Sisters

Rosenthal Two Sisters

Rosenthal Salambo

Rosenthal Wind Bride

Hutschenreuther Lucie Kieselhausen

Lucie Kieselhausen

Ruth St. Denis

Goldscheider Figures WMODA

Goldscheider Captured Bird J. Lorenzl

Niddy Impekoven Captured Bird Postcard

Niddy Impekoven Captured Bird Postcard