By Louise Irvine

On World AIDS Day, December 1, we are reflecting on the legacy of the Ardmore artists in South Africa who have died from the disease and those who live with HIV. More than 35 million people have died of HIV or AIDS since the virus was first identified in 1984 making it one of the most destructive pandemics in history. World AIDS Day was established in 1988, the first ever global health day. The red ribbon is worn to create awareness of HIV, remember those who have died, and show solidarity with the millions who live with HIV worldwide. There is still a vital need to raise money, increase awareness, fight prejudice and improve education.

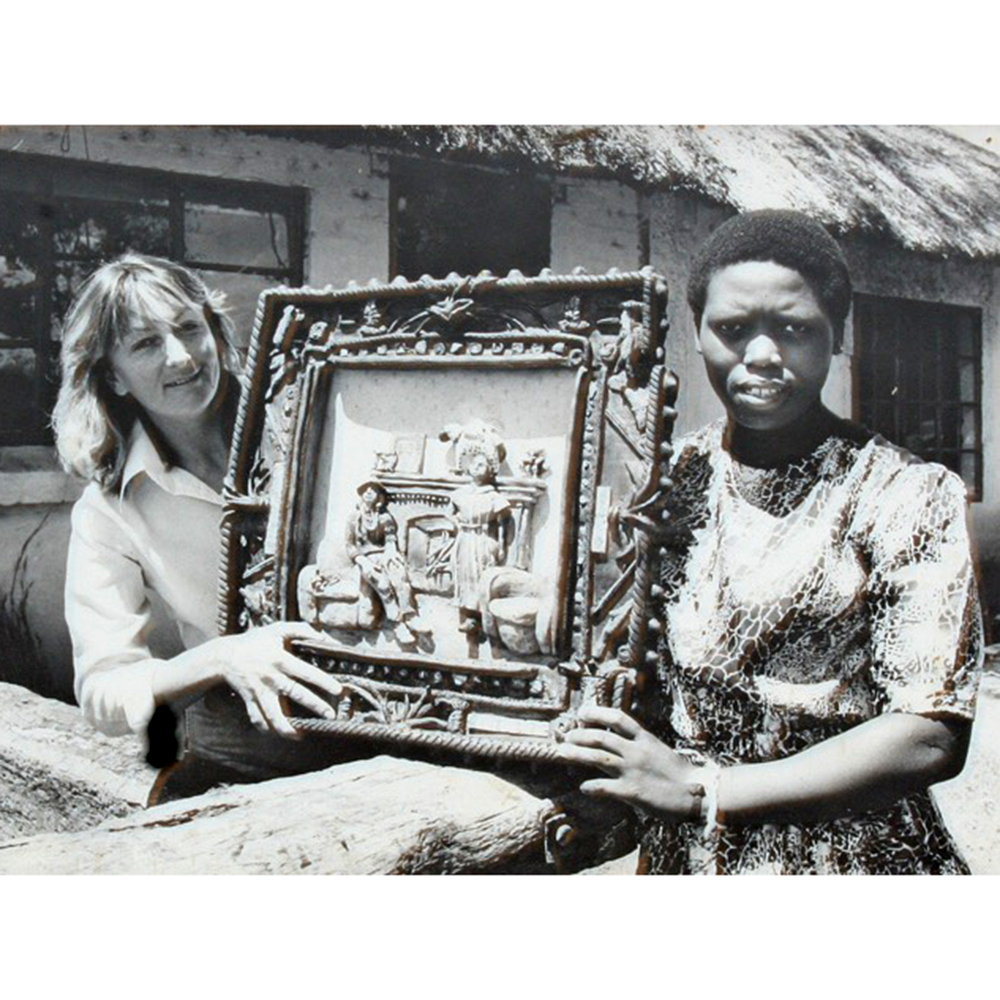

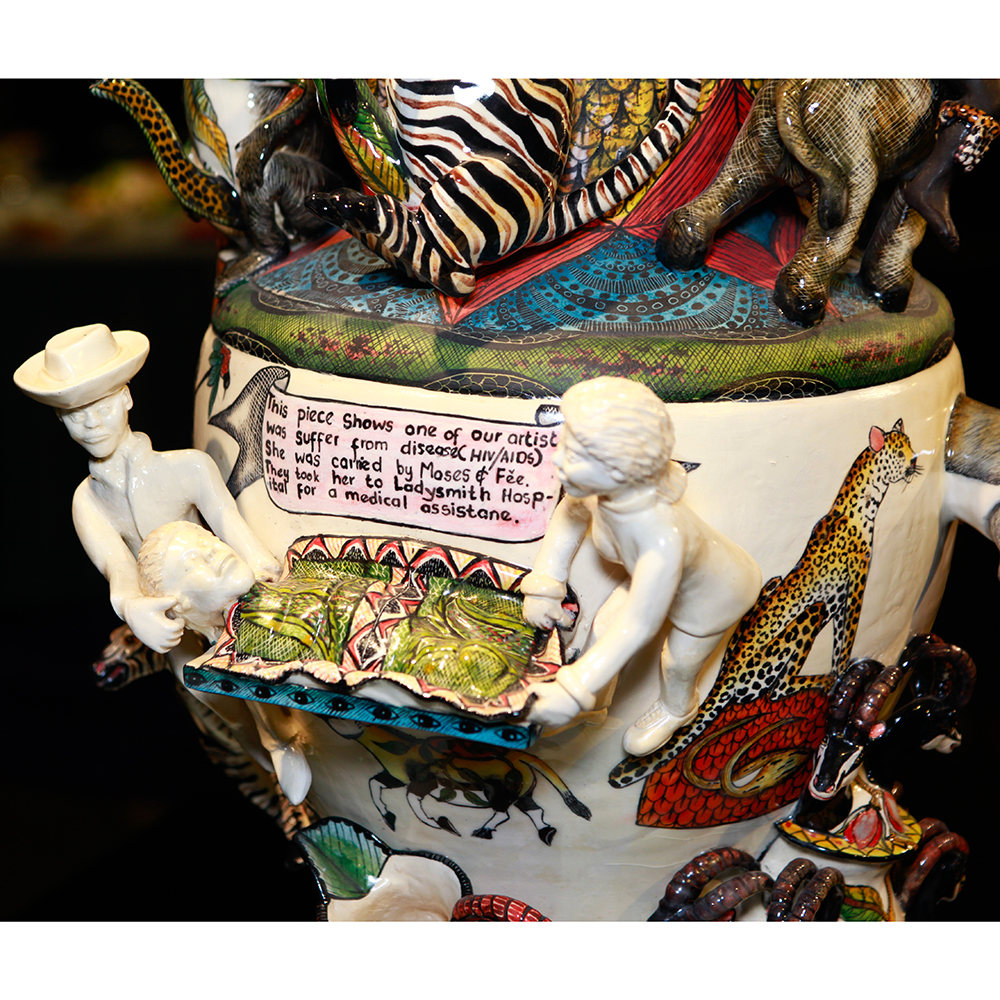

The Ardmore Studio has personal experience of the HIV/AIDS tragedy and each year the artists are involved in educational work in their community. When Fée Halsted started her ceramic studio at Ardmore Farm in 1985, Bonnie Ntshalintshali was her first assistant. The daughter of a farm laborer, Bonnie showed a natural talent for clay sculpture and thrived under Fée’s guidance. Together Fée and Bonnie won the prestigious Standard Bank award in 1990, which first drew national attention to their work and attracted new recruits to the studio. Punch and Mavis Shabalala grew up on Ardmore farm with Bonnie and they both became talented painters, inspired by traditional Zulu beadwork and weaving. In 1999, Bonnie died in Fée’s arms of an AIDS related illness, which was a big blow to the community. A short time afterwards, Punch became very ill and was on the brink of death. However, she was nursed back to health by Fée and her Ardmore team. Punch could not work for a year, and had to use a walker for some time, but she is now the senior lead artist at Ardmore. Punch’s personal battle is depicted on Ardmore’s 30th anniversary ewer at WMODA.

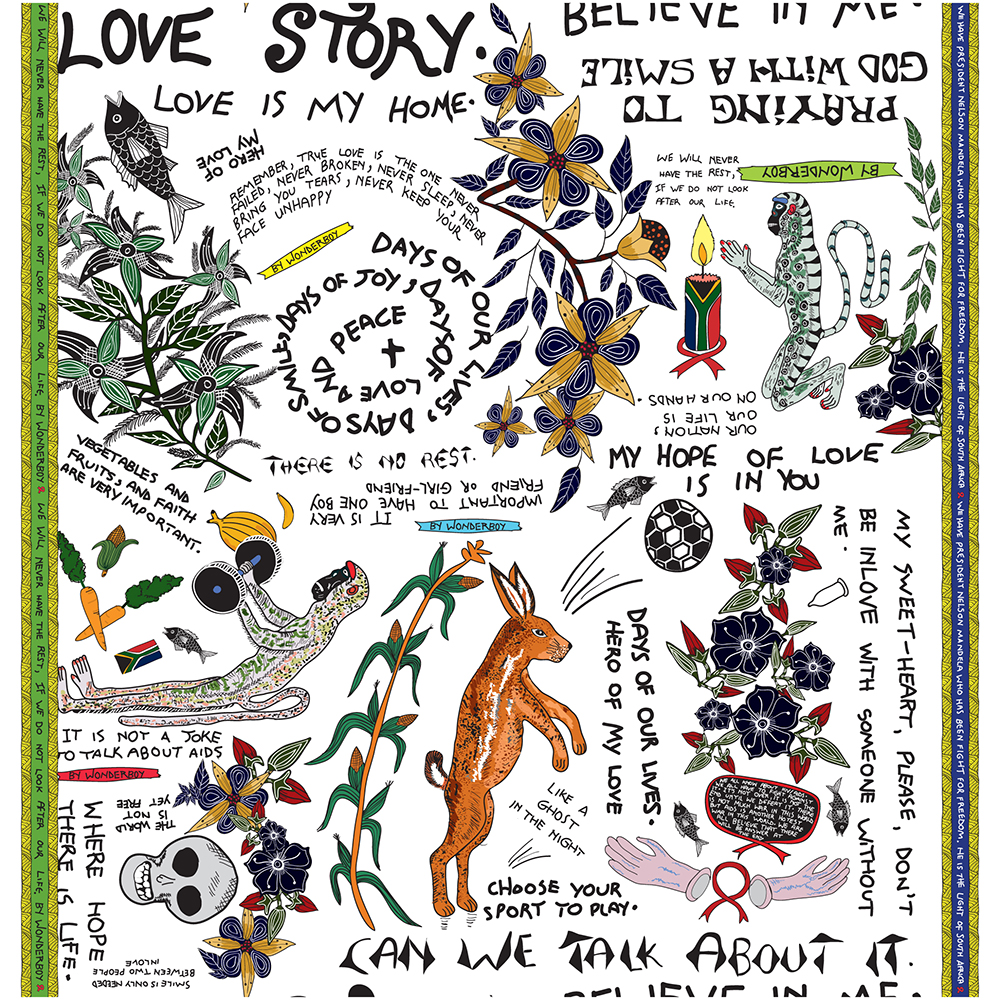

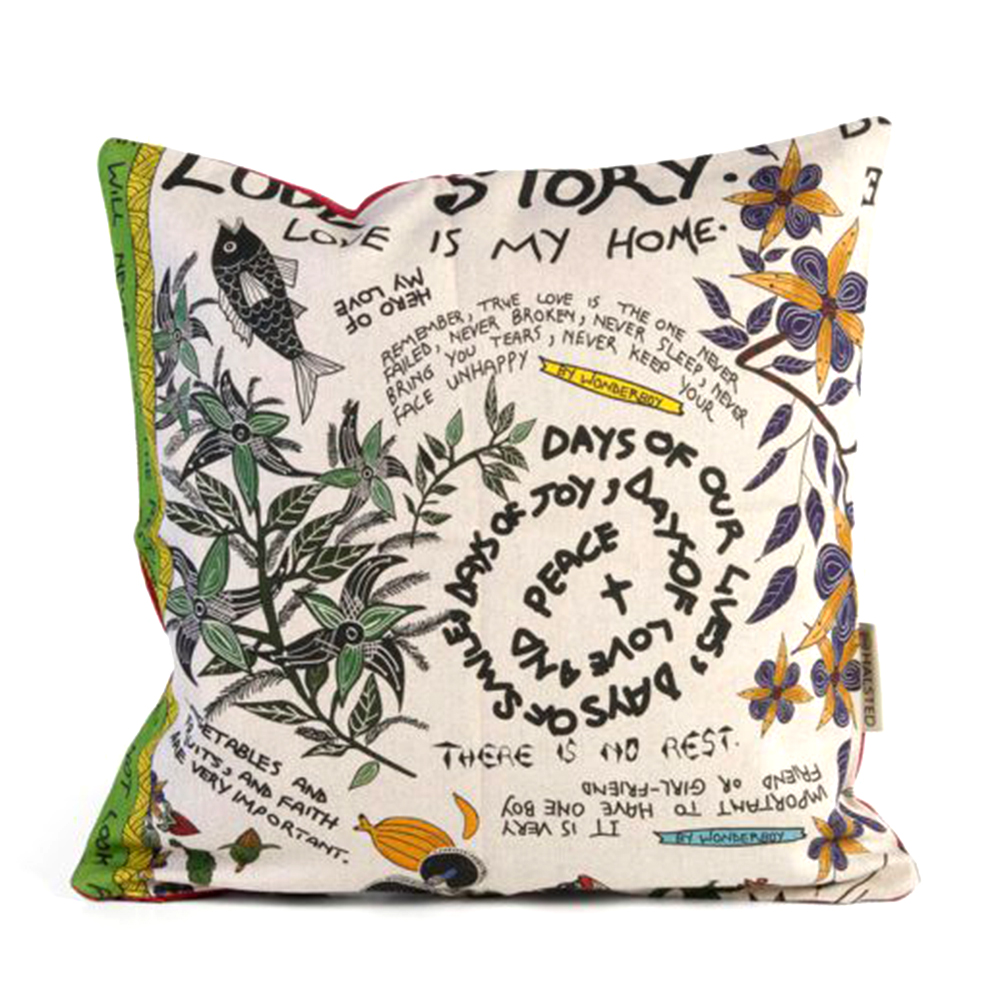

Sadly, Wonderboy Nxumalo was not so fortunate. He was an exceptional painter and poet who enjoyed relating stories from Zulu culture. He fought against prejudice and complacency in the face of the HIV/AIDS pandemic, which was a taboo topic in South Africa. Even the government refused to acknowledge its presence. Wonderboy challenged the silence and used his art to give advice about the dangers of the disease and how to combat it. In Zulu culture, it was a considered very bad form to speak ill of the dead, or to say that someone died of a dreadful disease. He used monkeys rather than humans as metaphors to reference the battle in his images. He combined humor and irony in his messages about the joys of love and the sorrows of HIV/AIDS. His hopeful prayers for a cure went unanswered and his death in 2008 saddened the Ardmore community. His legacy lives on in the Wonderboy Wisdom fabric with proceeds of the sale going to his family and a local orphanage for AIDS orphans.

Before anti-retroviral drugs became readily available in South Africa, Fée worked to ensure that medicine, good food and AIDS education was available to the Ardmore artists affected by the virus. However, skilled artists continued to die as many were in a state of denial. Condoms, which were freely available were not being used. Some sought the help of traditional healers, while others went secretly to witchdoctors to look for a scapegoat. Gradually a more enlightened approach to AIDS awareness inspired the artists to tackle the topic in a meaningful body of work which has been exhibited in Europe, South Africa and the USA. In 2010, the exhibition was part of the Global Africa Project at the Museum of Art and Design in New York. Ardmore’s 25th anniversary year was also significant in that it was the first year without further AIDS casualties at the studio. Of all Fée’s achievements, she is perhaps most proud of this.

Bonnie & Fée

Bonnie Ntshalintshali

Tribute to Bonnie Sculptures

Punch Shabalala

Punch Shabalala

Punch on a stretcher

Punch with her walker

Ardmore Vase by P. Shabalala

Ardmore Zebra Tray by P. Shabalala

Ardmore Vase by P. Shabalala

Elephant Vase by P. Shabalala

Ardmore 30th Anniversary Ewer

Ardmore 30th Anniversary Ewer detail

Ardmore 30th Anniversary Ewer detail

Punch’s Story on Tribute Ewer

Wonderboy Nxumalo

Wonderboy Nxumalo

Ardmore Plate by W. Nxumalo

Ardmore Plate by W. Nxumalo

Wonderboy Wisdom Fabric

Wonderboy Wisdom Pillow

Cup and Saucer by W. Nxumalo

Cup and Saucer by W. Nxumalo

Cup and Saucer by W. Nxumalo