The Great Stink to the Great Smog

by Louise Irvine

The current pandemic prompted me to look back through the archives to see how a pioneering Victorian potter responded to an earlier public health crisis. For centuries, fighting disease meant battling foul smells as the miasma theory was widely held. Many claimed that bad air and unpleasant odours could cause illness, a view that prevailed until the 1890s when viruses were discovered, and germ theory became more widely accepted.

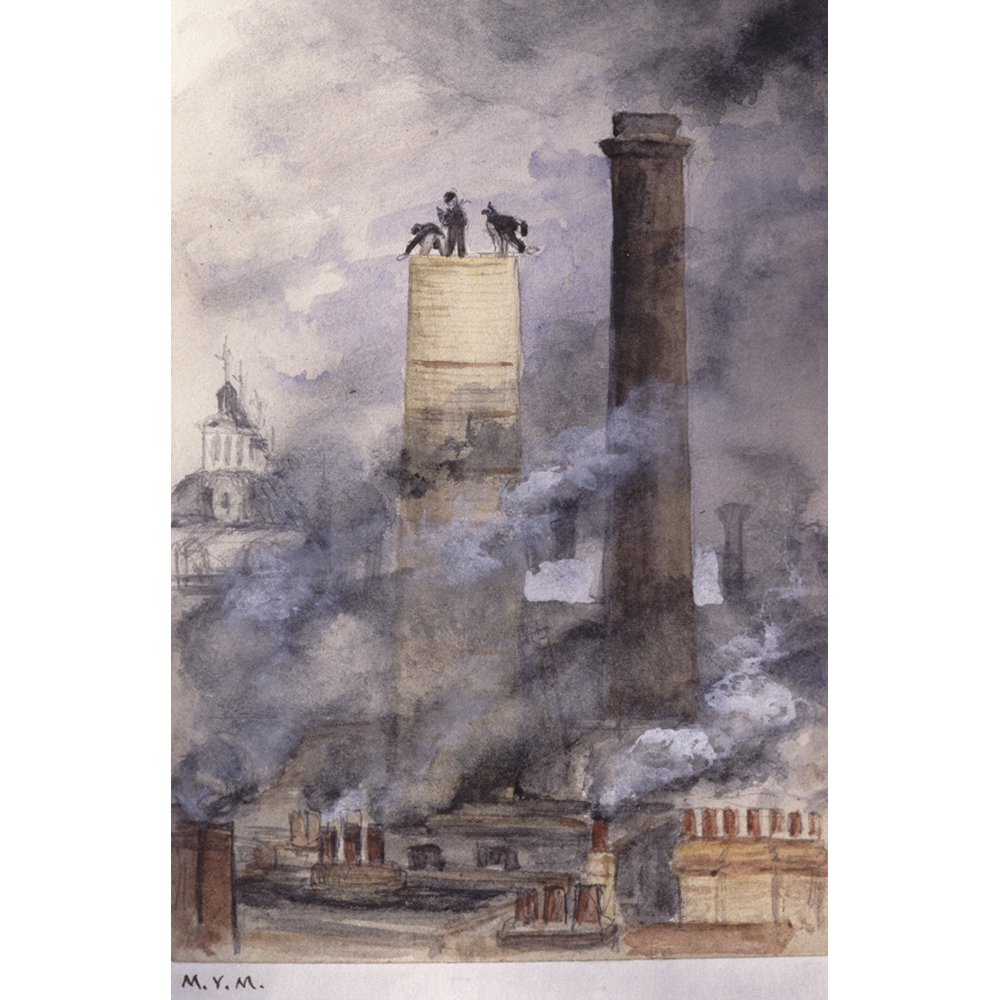

Major industrial cities were malodorous nightmares reeking of festering sewers, rotting carcasses in slaughterhouses, and noxious factory fumes. Killer diseases, such as as cholera, tuberculosis, yellow fever, and typhus could strike at any moment in the overcrowded unsanitary conditions. During the first half of the 19th century, the death rate in Britain’s cities was higher than at any time since the Black Death during the 14th century.

The Great Stink

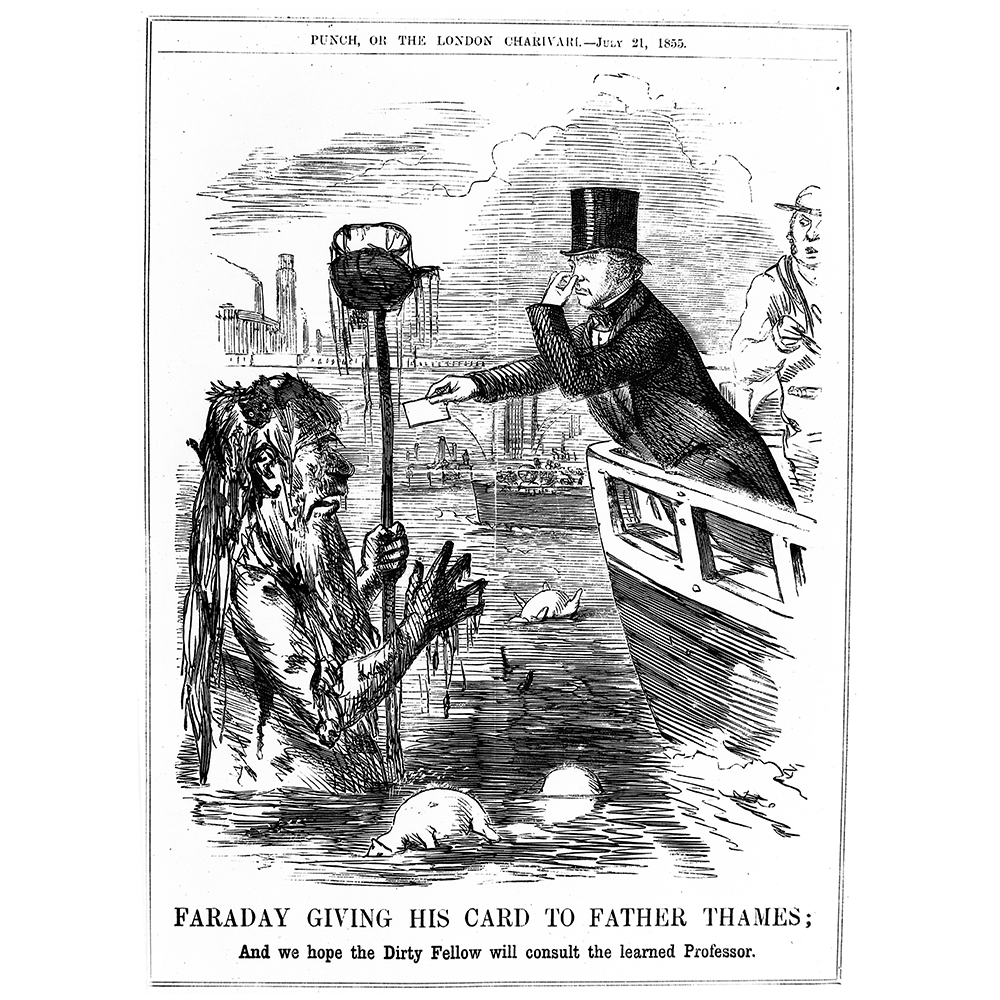

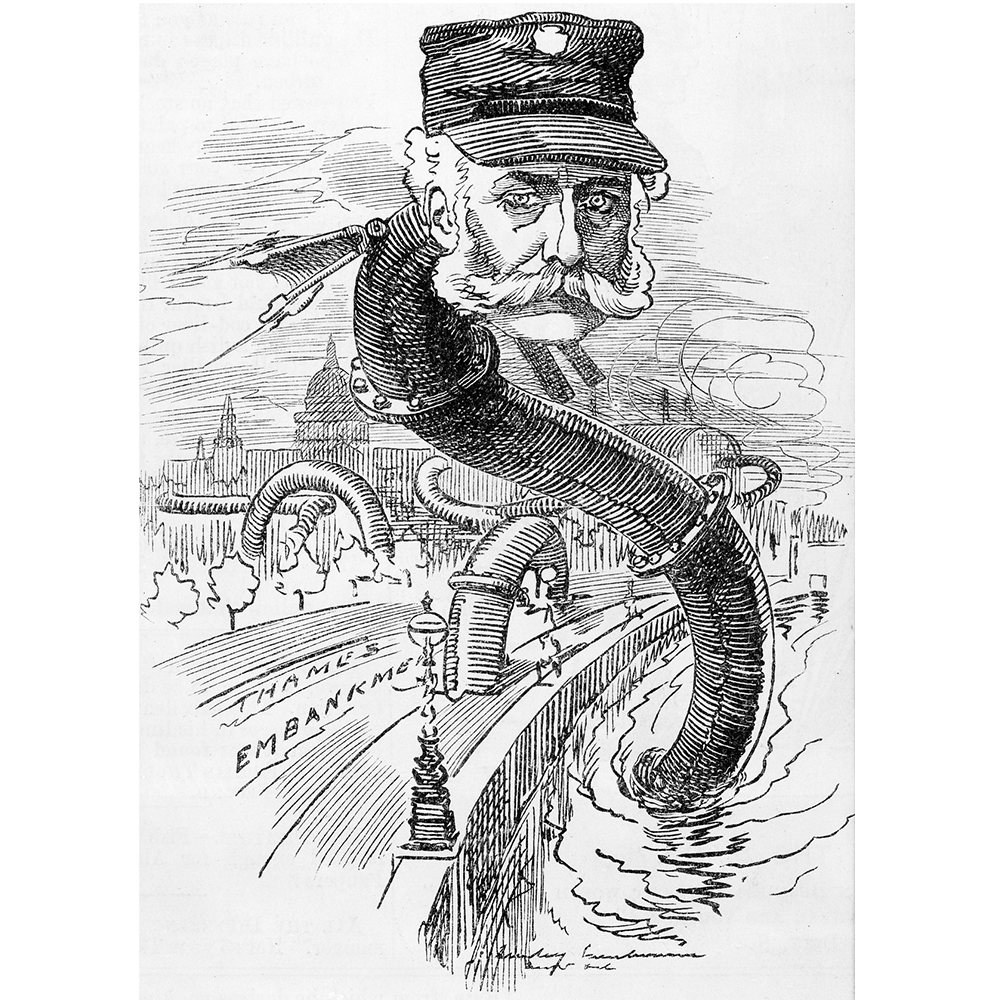

Miasma from the River Thames was blamed for transmitting contagious diseases, even though Sir John Snow, a London physician, demonstrated that cholera was waterborne and caused by contaminated supplies. During the Great Stink of 1858, a hot summer exacerbated the smell of untreated human waste and industrial effluent that emptied directly into the river. The stink was so bad in the Houses of Parliament that the curtains were soaked in bleach to alleviate the odor. Victorian men and women carried perfumed handkerchiefs and nosegays in the streets and buried their noses when the stench became unbearable. Appropriate government response finally came with plans to build a new sewer network for London. Over the next 16 years, civil engineer Sir Joseph William Bazalgette masterminded 82 miles of main sewers, 1100 miles of street sewers, 4 pumping stations, 2 treatment works and 3 embankments.

The Doulton Lambeth Pottery

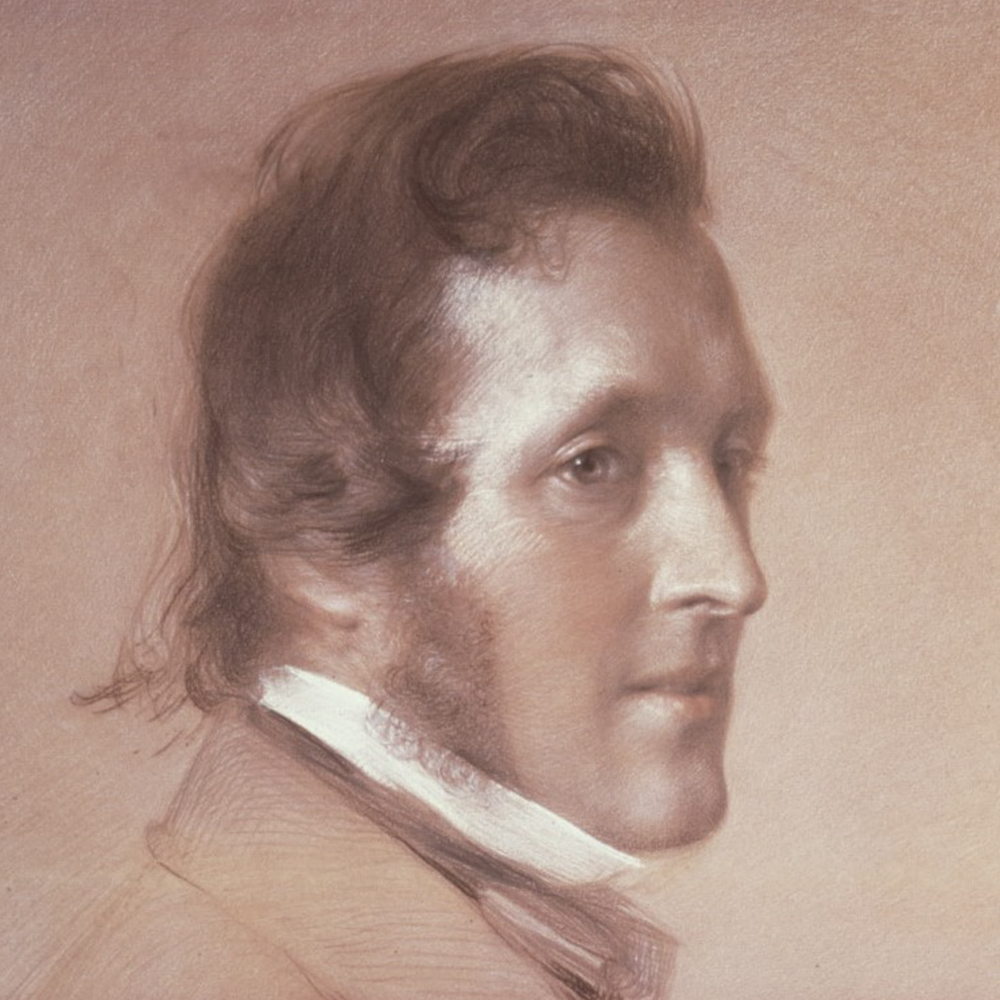

The Lambeth district of London, where the Doulton pottery was founded in 1815, was a hotbed of disease. It was particularly smelly with its bone-boiling and manure works on the banks of the River Thames. Henry Doulton, the son of the founder, was very sensitive to these appalling conditions when he began his career at the Lambeth pottery in 1835 at the age of 15. According to his biographer, Sir Edmund Gosse, he was hurrying along Naked Boy Alley with his handkerchief pressed to his nostrils when he realized that “there are few bigger tasks for a plain man to accomplish than the resolute and efficient drainage as such sinks of pollution as this.”

Henry Doulton soon became convinced that the salt-glaze stoneware water pipes that his father had been making since the 1820s had wider applications. In the 1840s, sanitary engineers began to advocate the use of impermeable, non-corrosive stoneware pipes for the disposal of sewage to replace the inadequate flat-bottom drains of porous bricks that harboured disease. The chief protagonist, Edwin Chadwick, who became known as “The Father of Sanitary Science”, published a disturbing 'Report on the Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population' in 1842.

Henry Doulton followed the research and debates of the sanitary reformers in the burgeoning public health movement with great interest. He predicted that the future demand for stoneware pipes would be beyond the scope of his father's factory. Accordingly, in 1846 he established his own business in High Street Lambeth, exclusively for the manufacture of drainpipes. The Public Health Act of 1848 greatly aided the development of his drainpipe business and in that year, Henry Doulton acquired another works at Rowley Regis, near Dudley in Staffordshire to supply the Midlands area, which went on to become the largest drainpipe factory in the world.

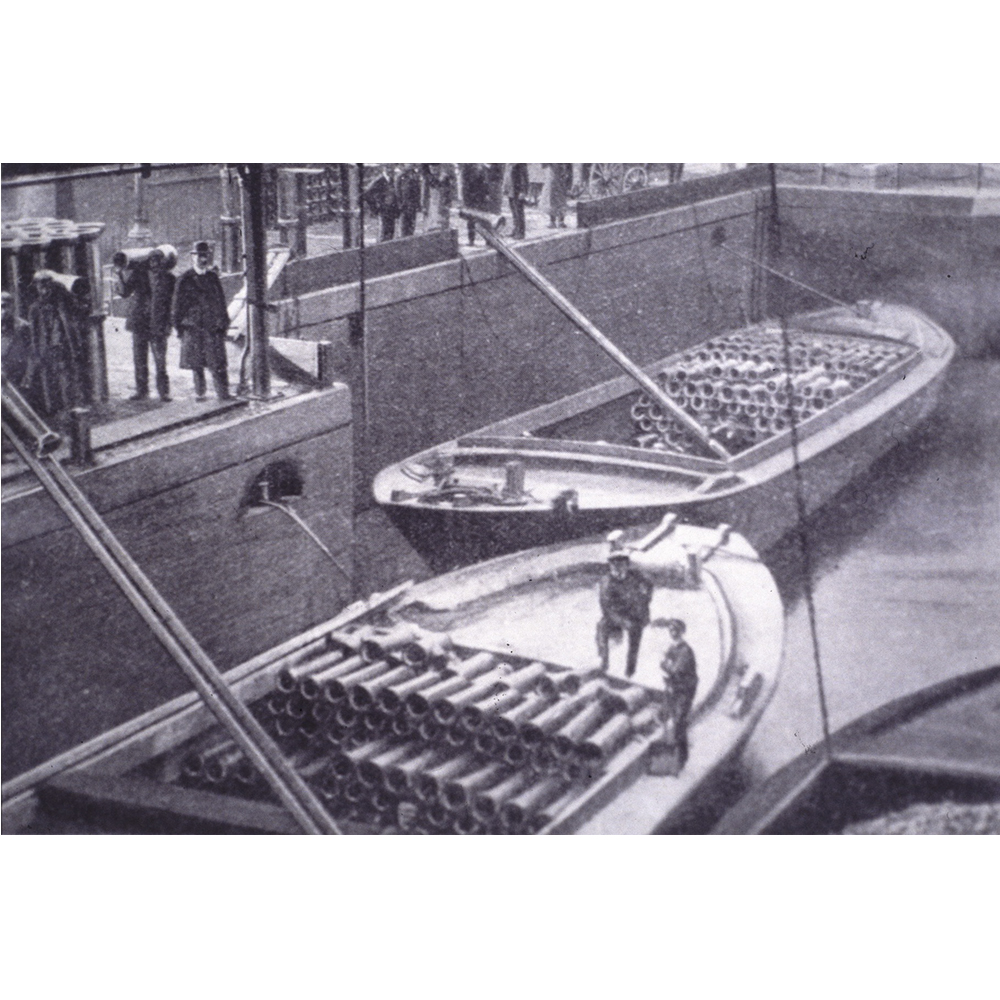

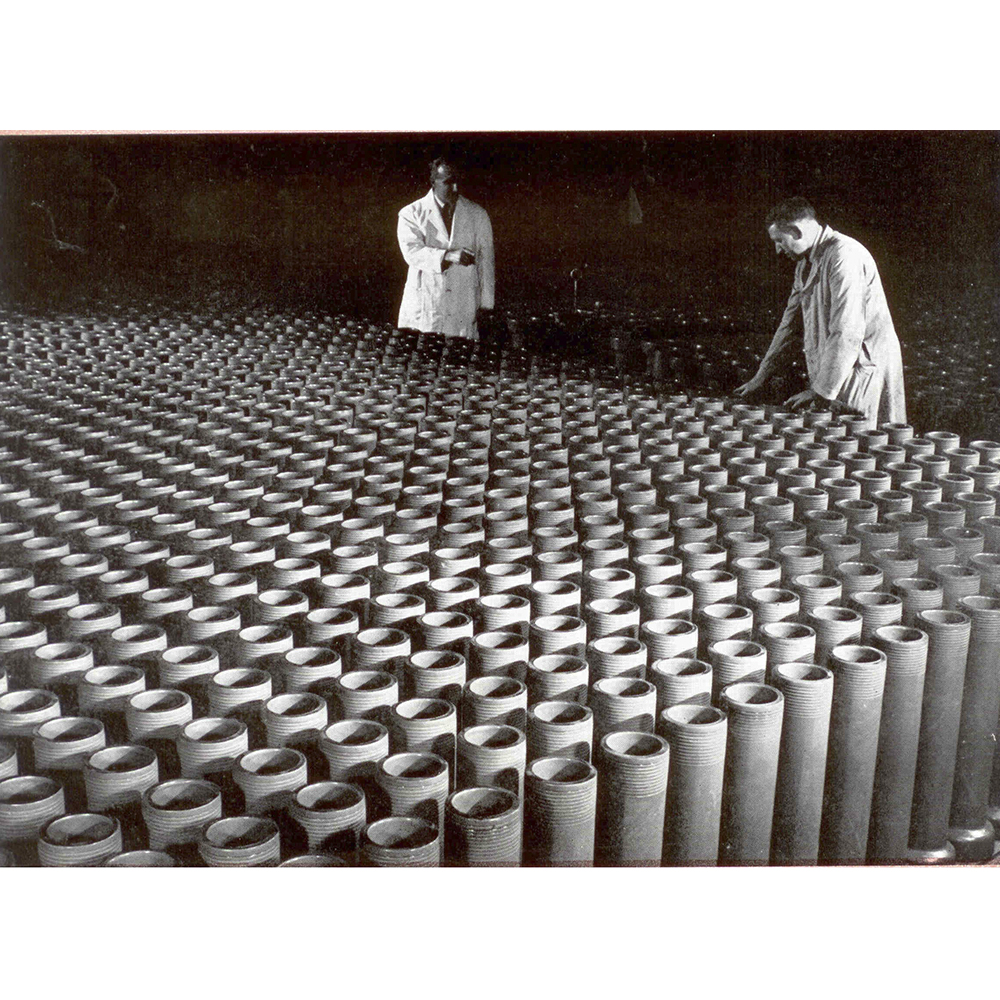

Doulton's first stoneware pipes were thrown on the wheel but suitable steam powered machinery, using metal dies for extruding the clay, was soon developed for making circular pipes for the efficient flushing of sewage. Henry Doulton also concentrated on perfecting sound, water-tight pipe joints and was one of the first manufacturers to recognise the need for flexibility to compensate for the inevitable settlement after the pipes had been laid. By the 1870s, Henry Doulton had supplied drainpipes for the London sewer system and developed a large export trade. For the next fifty years the company supplied sewers for many European cities as well as for countries further afield, such as India, Australia, Argentina, and Brazil. By 1899 the combined output of all the Doulton works amounted to over 30 miles of pipe a week.

Doulton’s pipe business flourished at regional factories in Britain during the 20th century but production stopped in London in 1956 due to the world’s first Clean Air Act. This British government legislation was prompted by the Great Smog of December 1952, when Londoners were trapped in a deadly cloud of fog and pollution for five days. Smog was a regular problem in the most overpopulated and industrialized city in the world. Smoke from coal fires for heating homes and power generating stations stagnated in the cold air most winters. However, the prolonged crisis choked more than 12,000 people to death. Photographs from the time show Londoners wearing masks just like today. Let’s hope scientists find a vaccine soon for today’s public health crisis.

Read more about Royal Doulton’s contribution to sanitation and health in From Sewage to Sung

Faraday Father Thames Great Stink

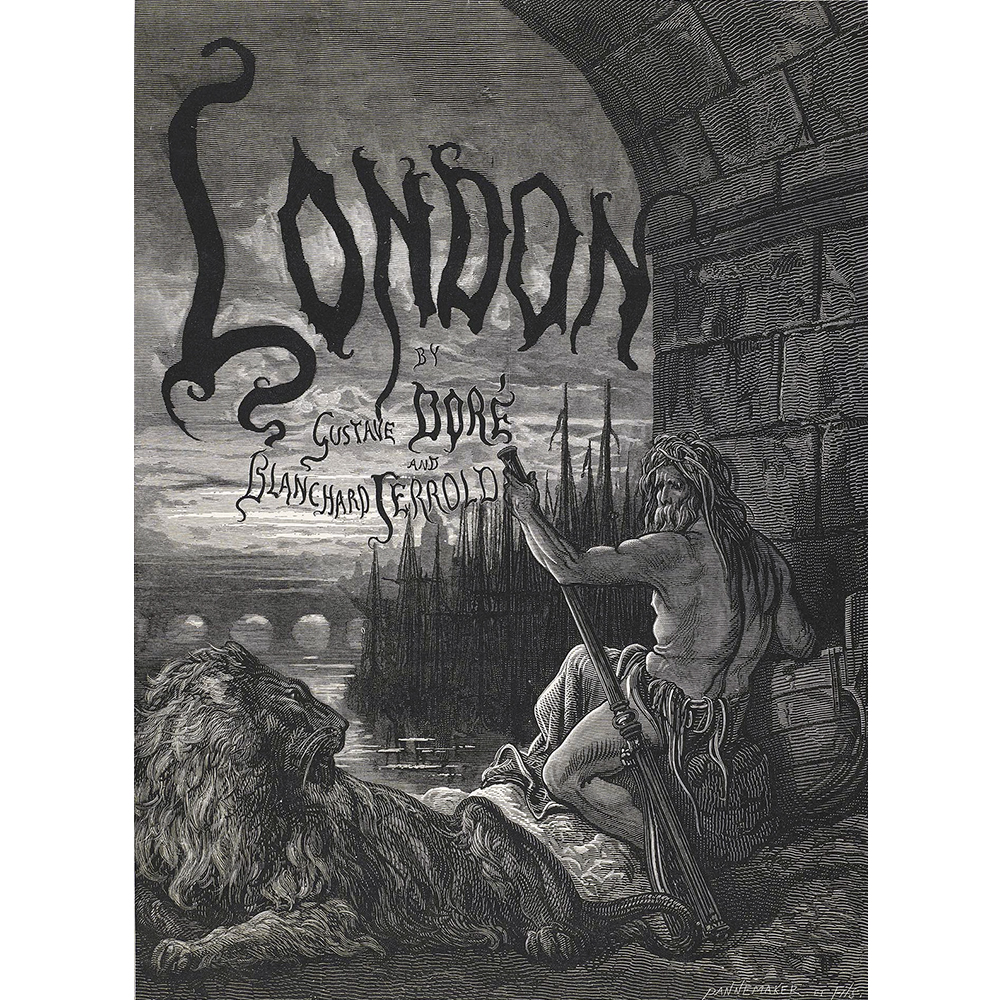

London by G. Dore

Bazalgette Sewer Snake Punch 1883

Doulton Drainpipe Wharf c1870

Loading drainpipes at old dock Lambeth

Henry Doulton

Doulton Pipe samples

Drainpipes

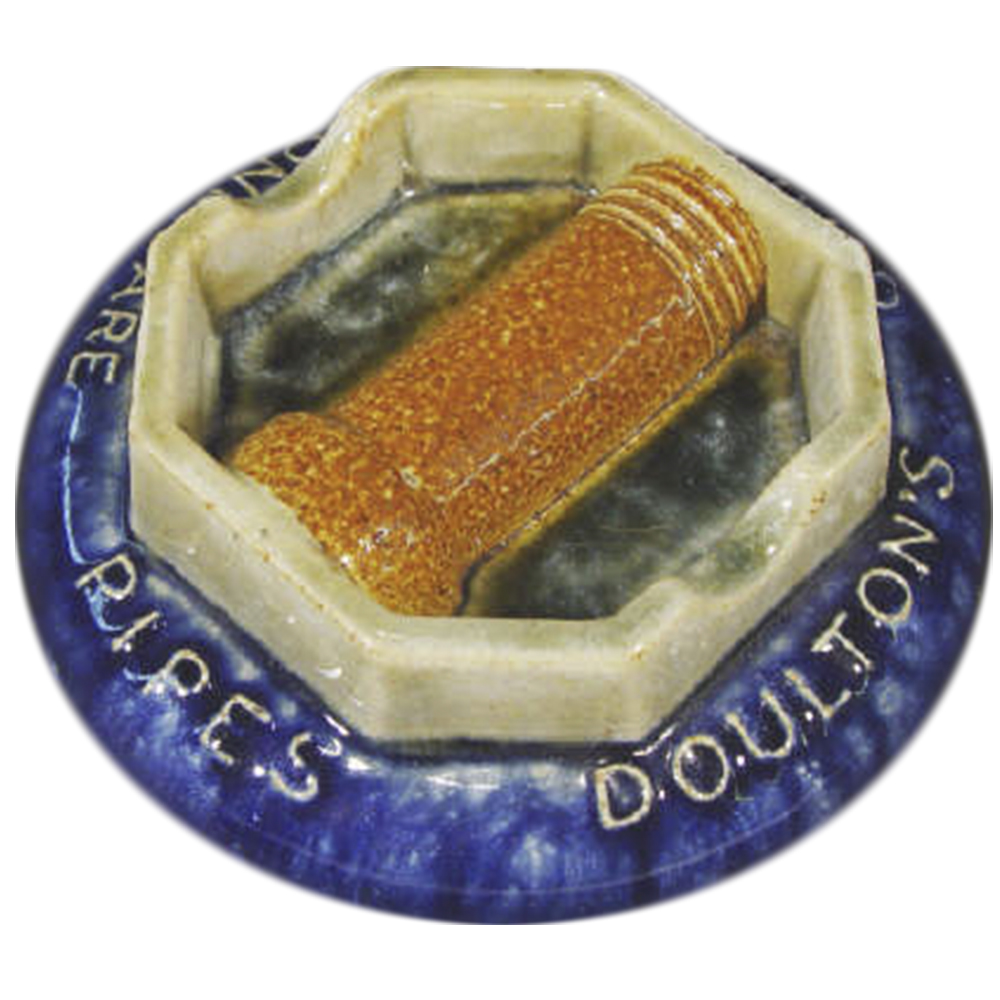

Doulton Drainpipe Ashtray

Doulton Sink and Drainpipe Ad

In Progress by M.V. Marshall

Doulton Lambeth Potteries

Woman wearing mask in 1952 London

Masks in fog bound London