by Louise Irvine

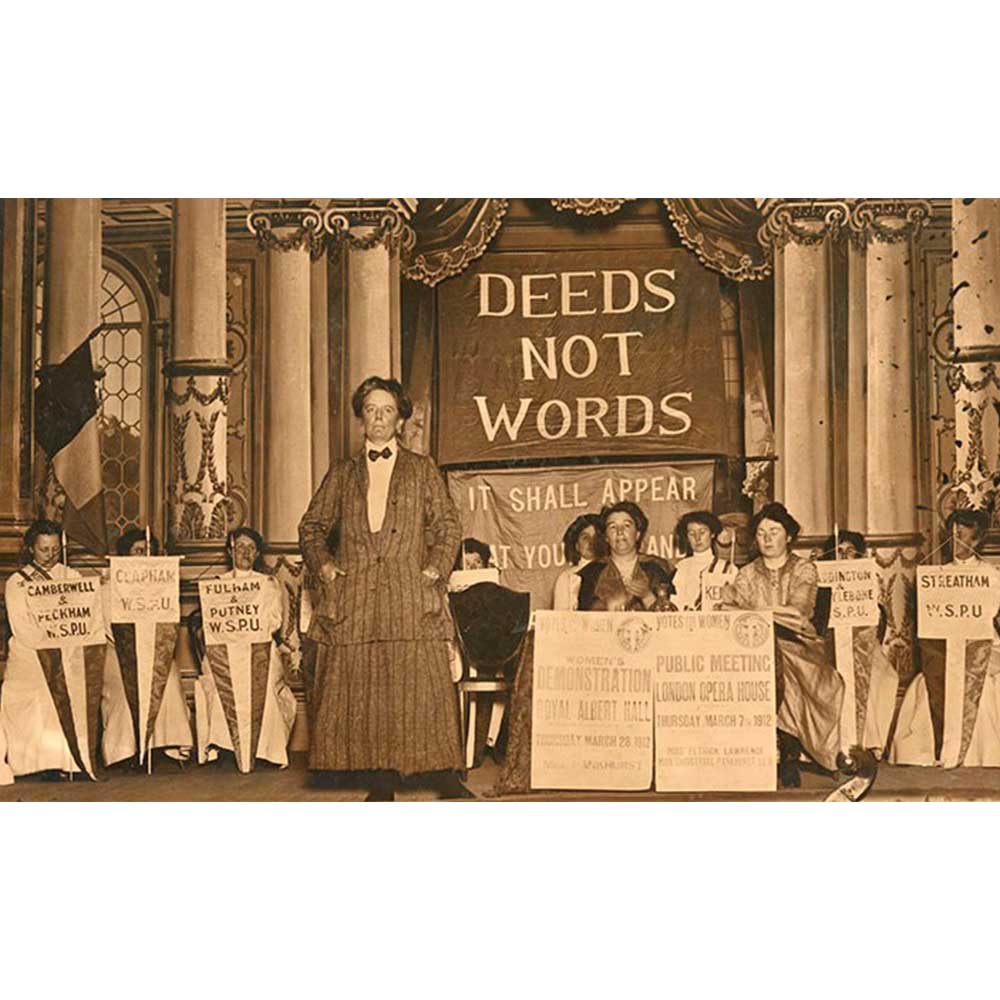

“Votes for Women” was the rallying cry until August 1920, when all American women were finally enfranchised. In Britain, agitation for women’s suffrage first succeeded with “Deeds Not Words” in 1918 and was equalized with men in 1928. Women also struggled to assert their rights in the workplace as can be seen in the British pottery industry.

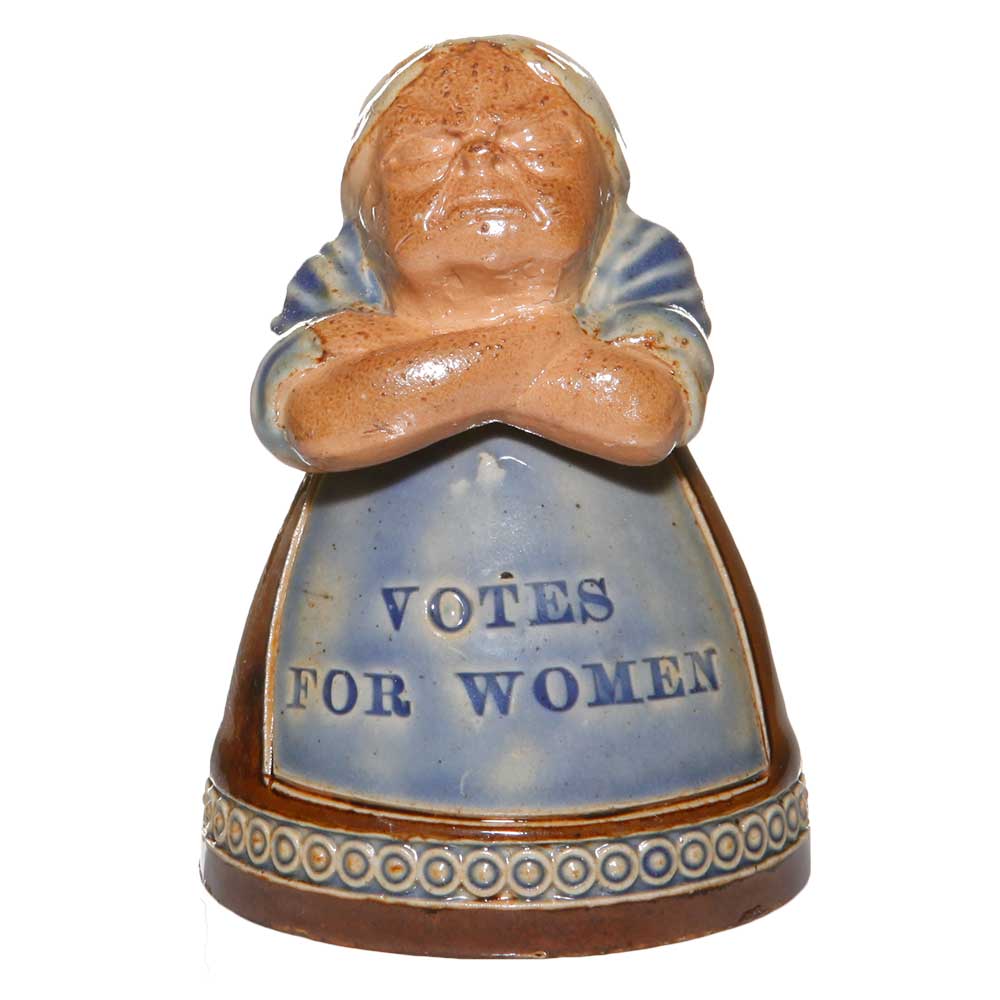

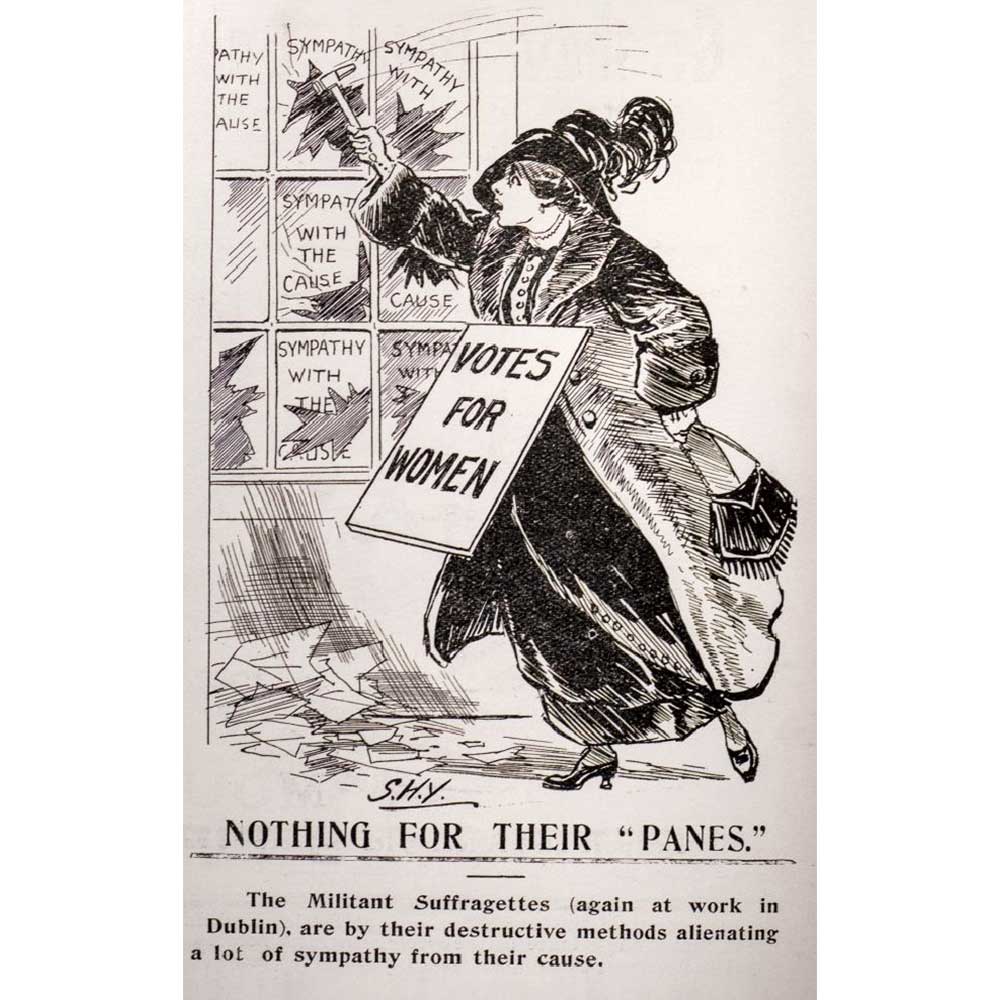

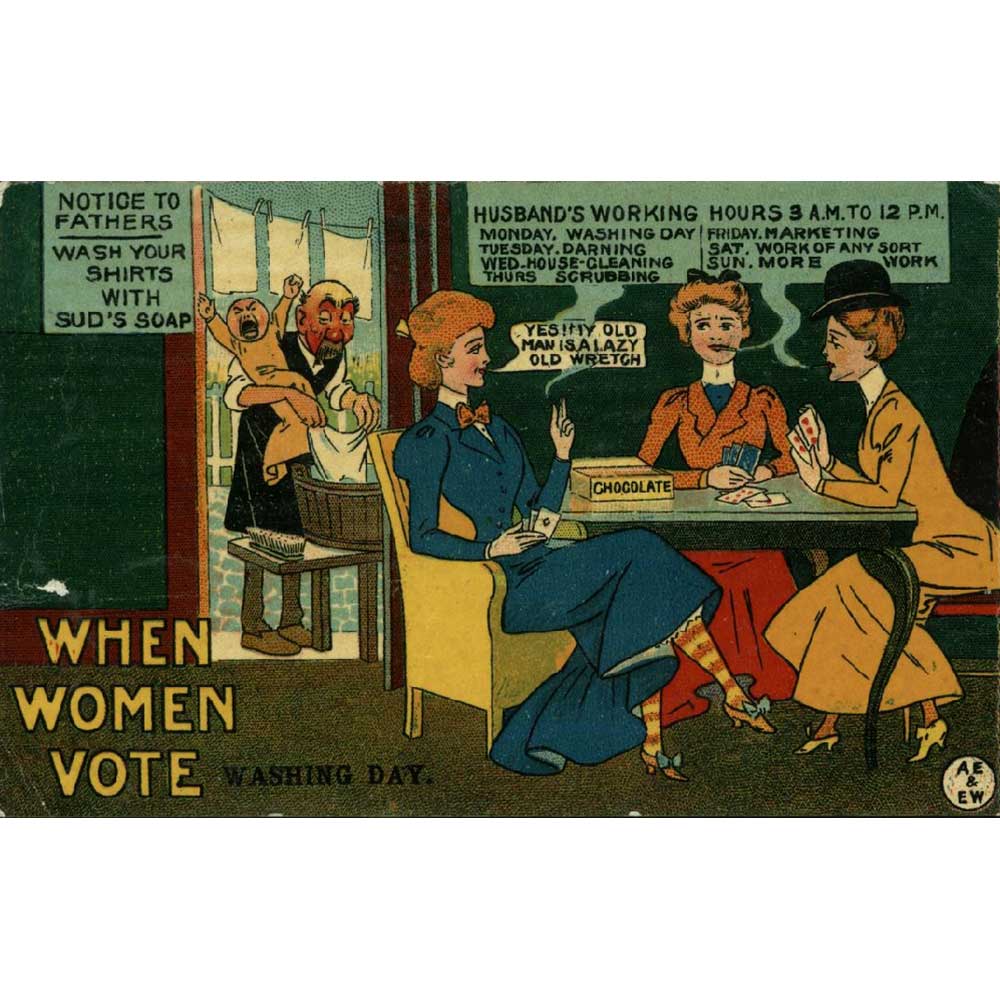

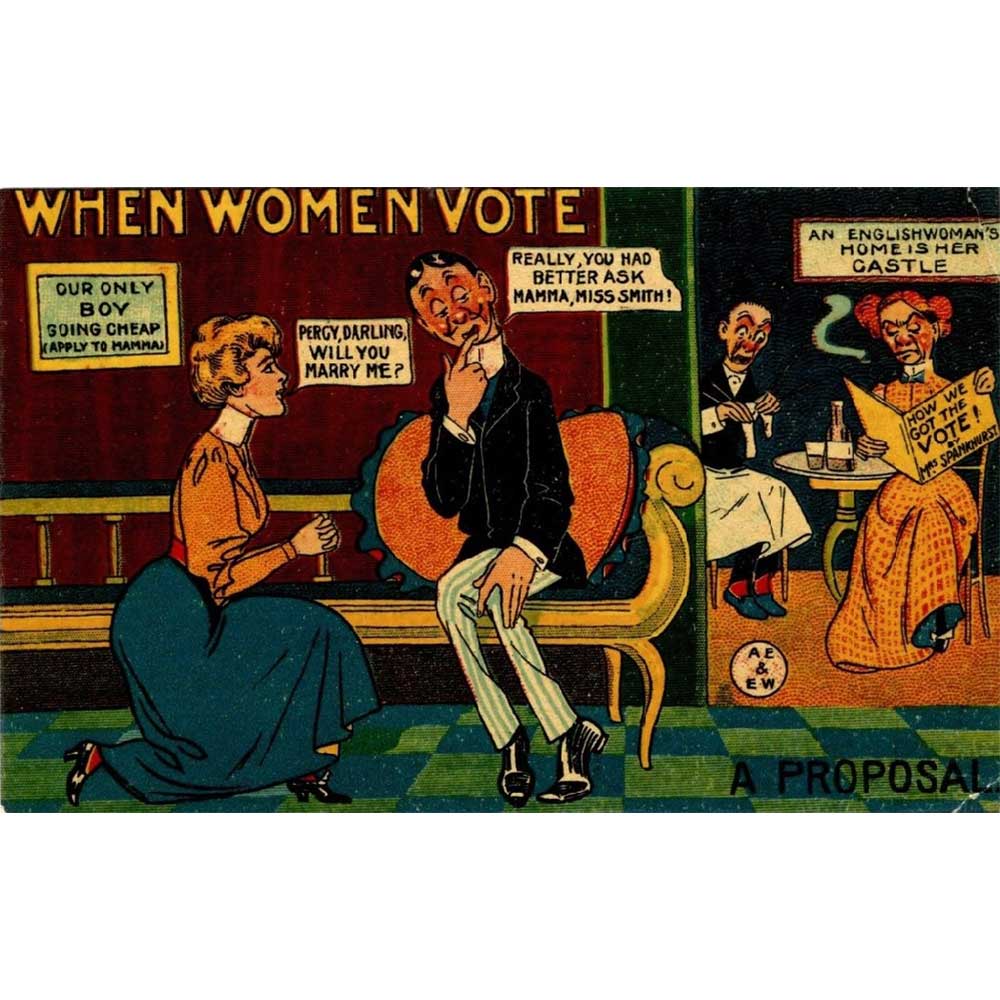

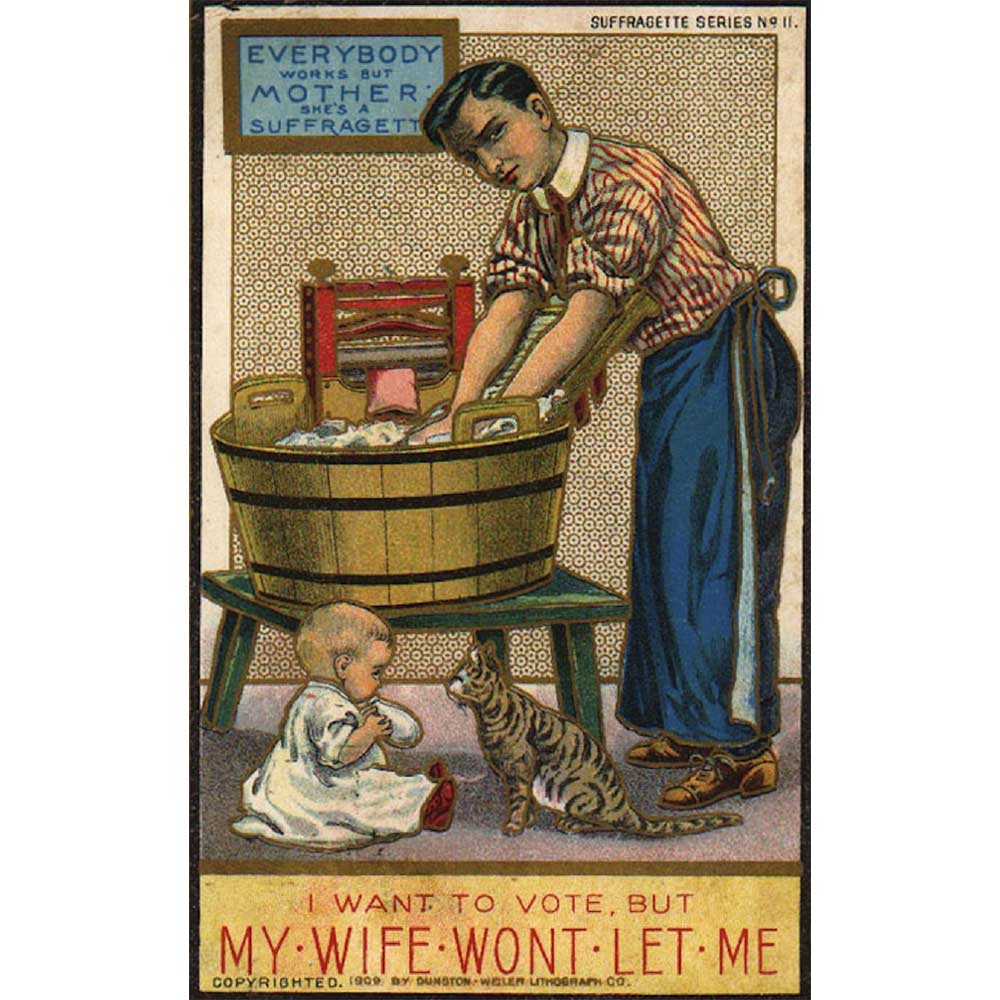

The women’s rights movement began in the USA nearly a century before the vote was finally granted. Some US states had given women the right to vote by the end of the 19th century but the constitution was not ratified for all women until August 20, 1920. Across the Atlantic, militant British suffragettes believed in “Deeds not Words.” They broke windows, started fires and went on hunger strike when they were arrested. Cartoonists lampooned their excesses and the Doulton pottery produced inkwells of an ugly woman and her baby mocking the movement. In 1918, the vote was given to British women aged 30 or over, which was reduced to 21 ten years later. However, getting the vote was just one of the challenges faced by working women.

Angel of the Household

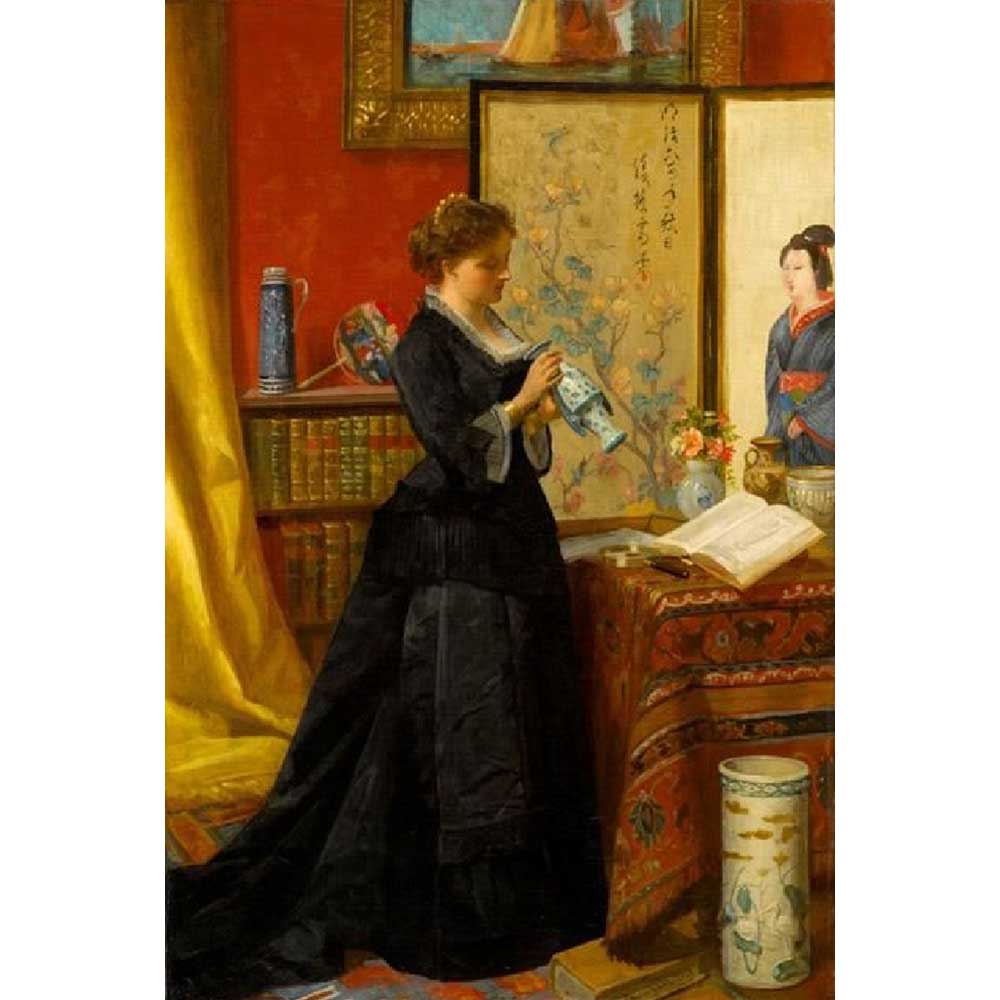

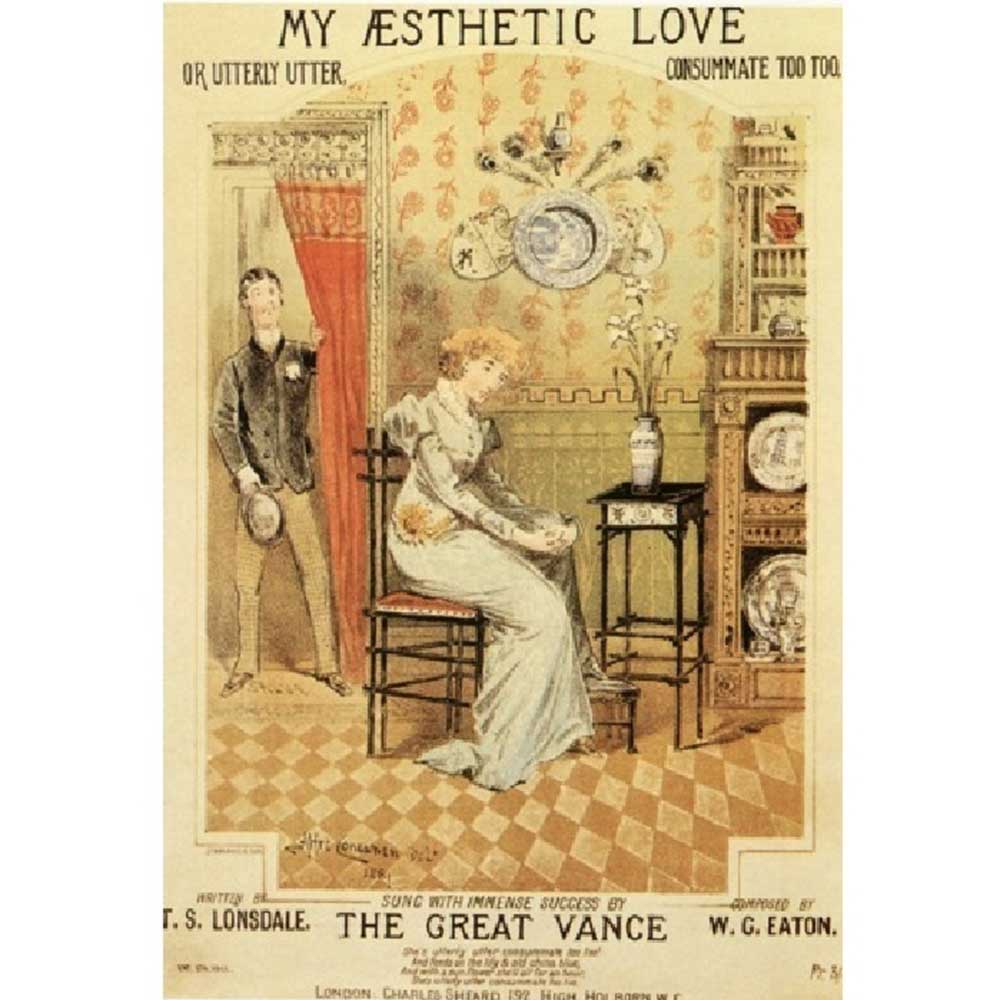

During the Victorian era, a woman’s place was in the home as the “angel of the household” and formal education was not customary for girls. Ambitious young women with a talent for the arts could enroll at the National School of Design in London which was opened for women in 1842. The school catered to gentlewomen, aged 13 to 30, who demonstrated a need to work. One of the more preposterous suggestions to deter those who left artistic careers to marry was that only ugly women be admitted to art schools!

Art Pottery Studios

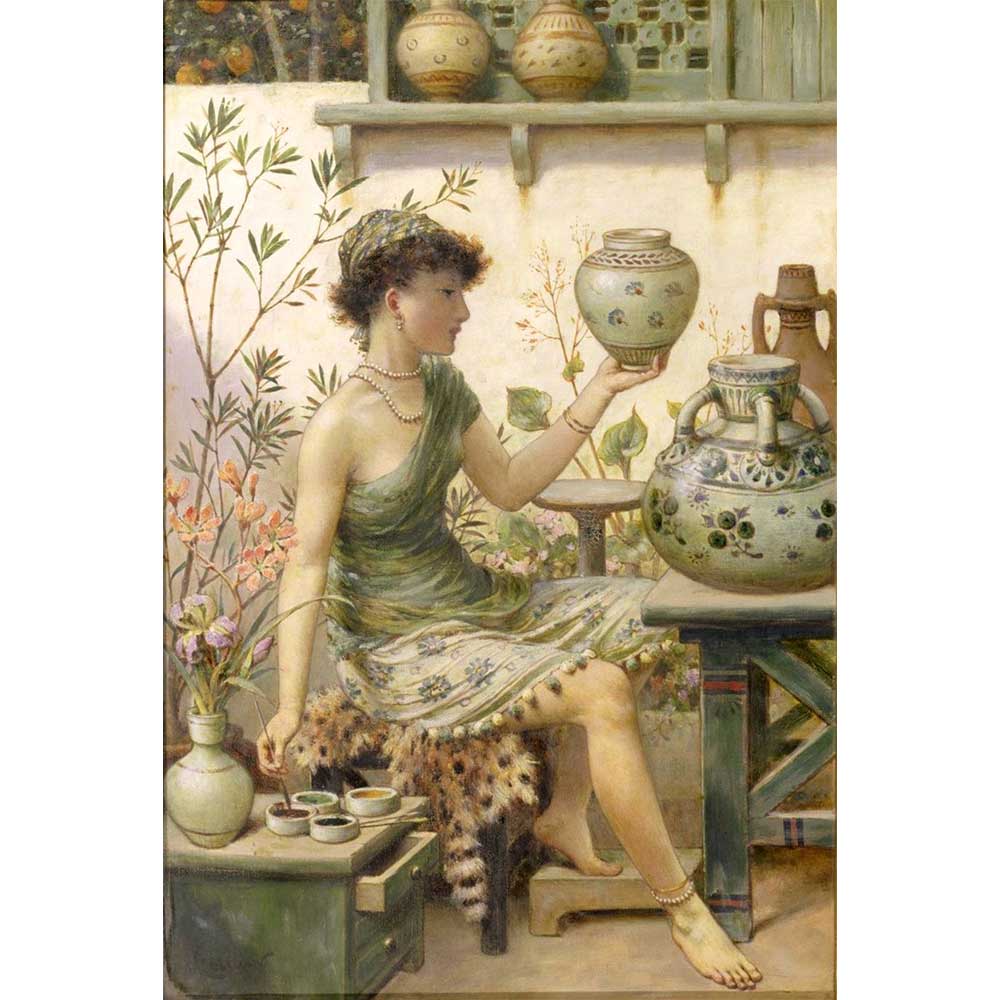

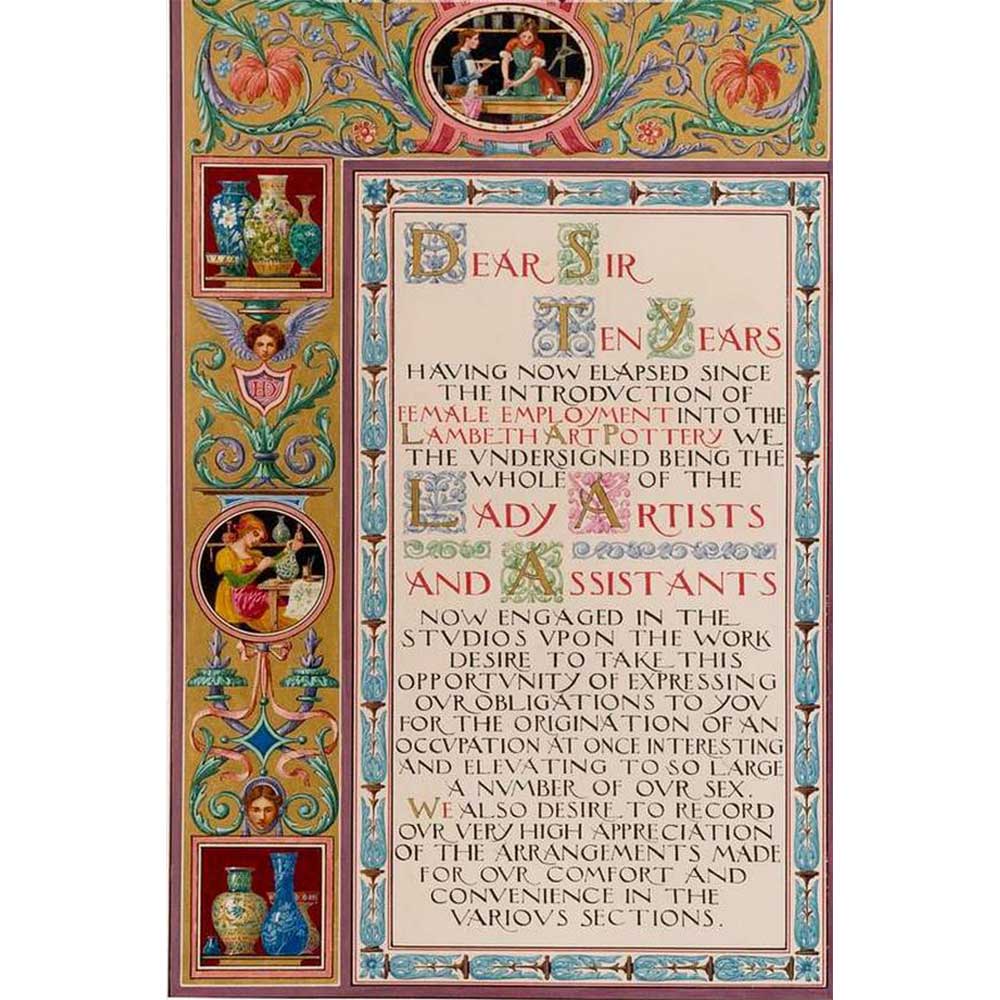

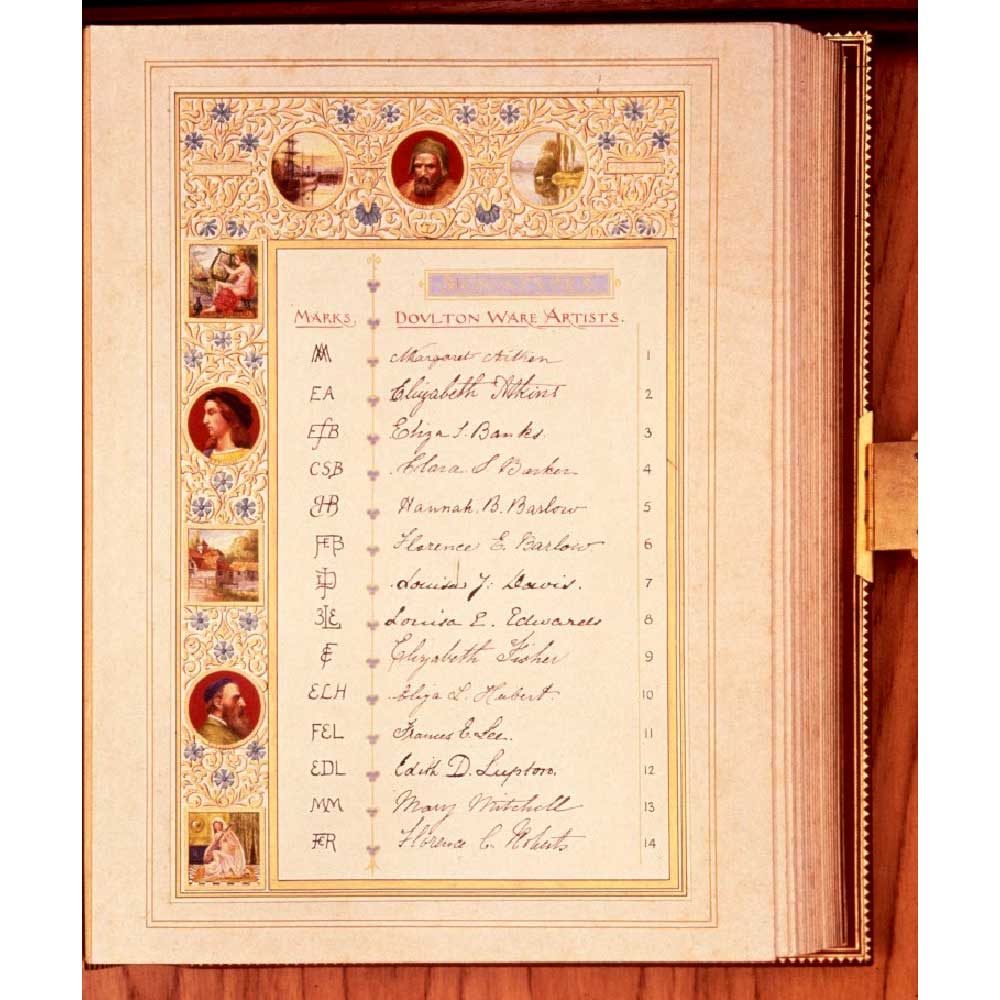

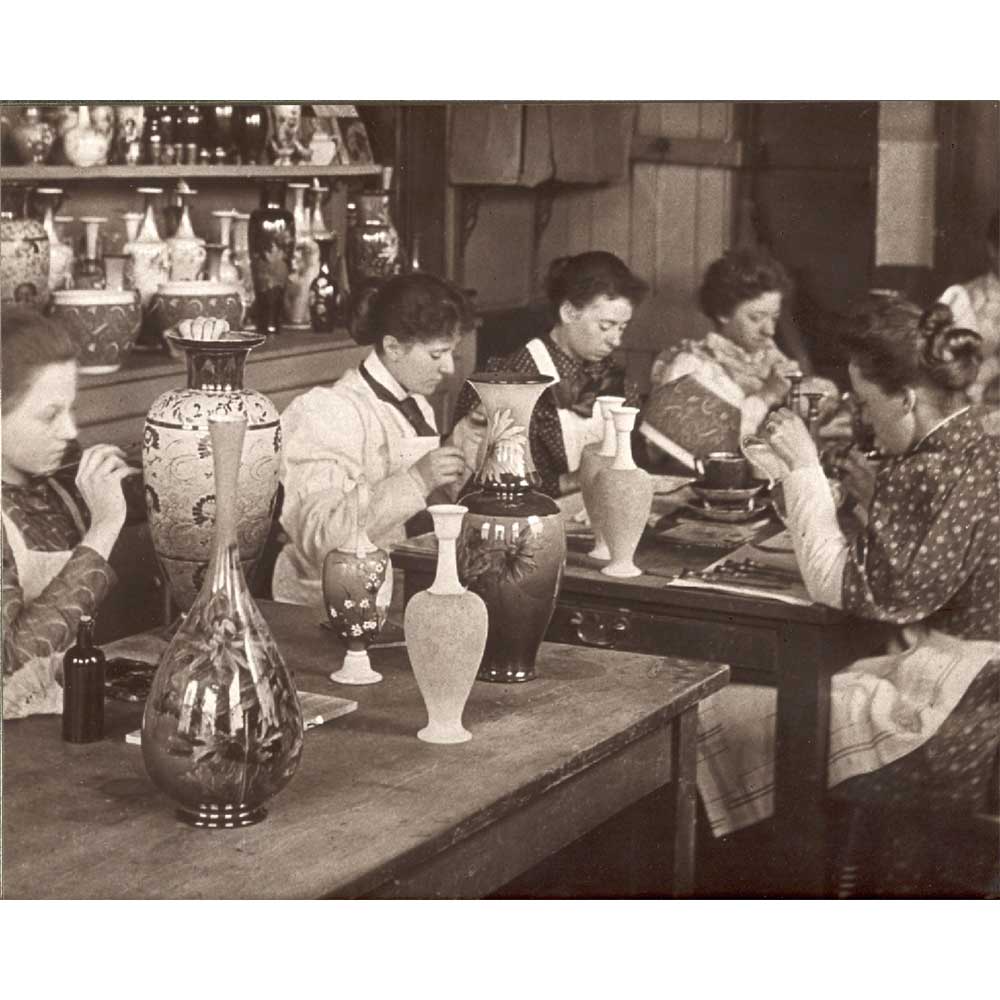

In 1871, encouraged by the success of this venture, Colin Minton Campbell set up the Minton Art Pottery Studio next door to the school and around 25 ladies were employed to paint on pottery. When the Minton studio was destroyed by fire in 1875, some young women found employment at Doulton’s new art pottery studio, which was established in 1872 in collaboration with the Lambeth School of Art. Typically, girls began their Doulton careers at the age of 13 and their wages increased for each government exam that they passed. Many were taught by Miss Florence Lewis, who wrote the first guidebook on pottery painting. To mark the 10th anniversary of their employment, 229 lady artists of Lambeth presented Henry Doulton with an illuminated album “to take this opportunity of expressing our obligations to you for the origination of an occupation at once so interesting and elevating to so large a number of our sex.”

Paradoxically, Sir Henry did not support the agitation for women’s rights. He believed the “true sphere of woman is the family and household….” and they should focus on “the Arts that beautify and adorn life.” Typically, his artists had to put down their paintbrushes when they married. His travels on the Continent had prejudiced him against women doing men’s work as he believed it encouraged indolence in men. He abhorred strenuous labor for women and resolved to eliminate it.

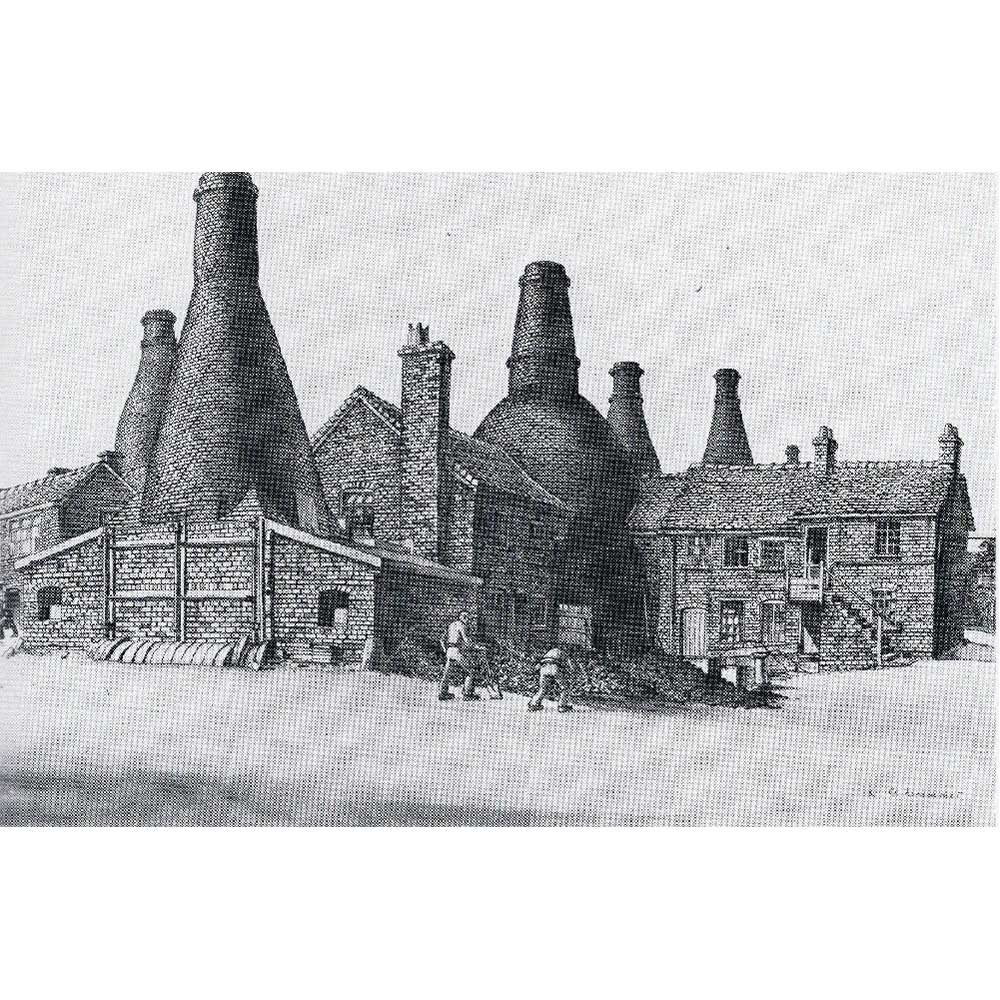

Staffordshire Potteries

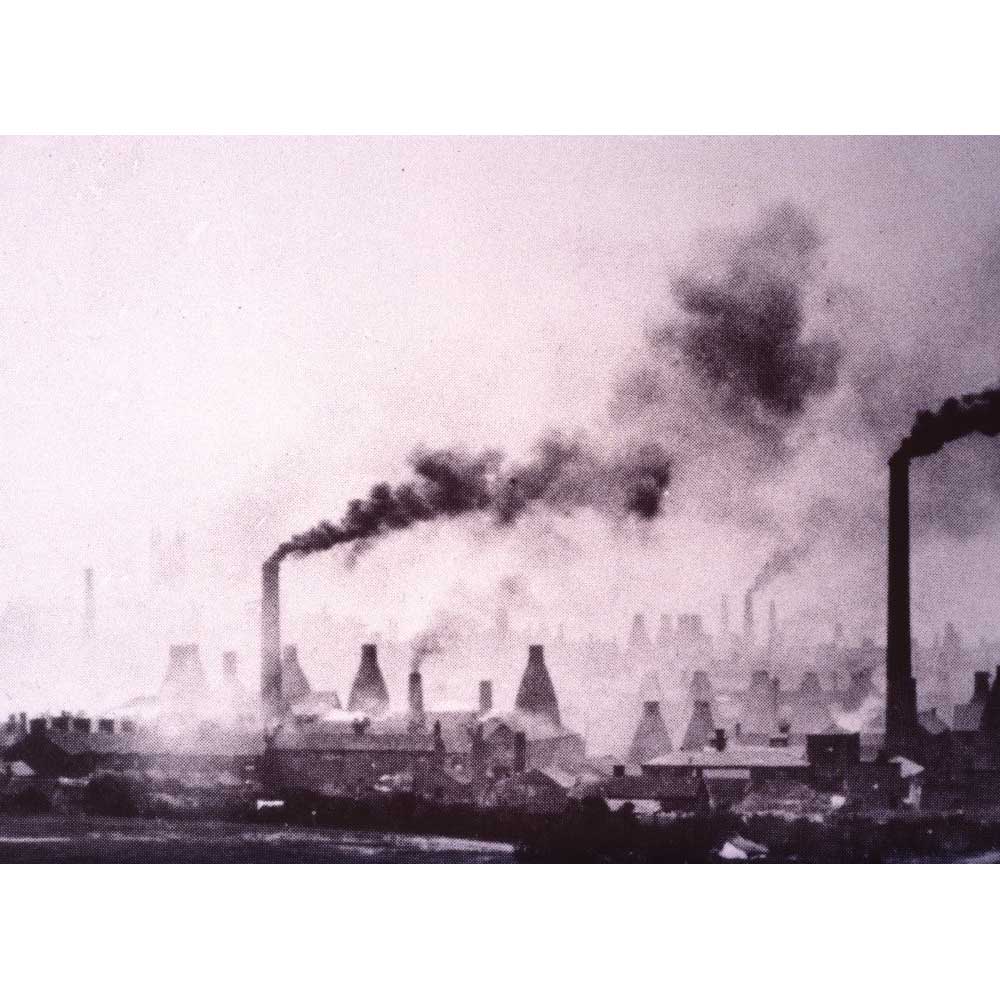

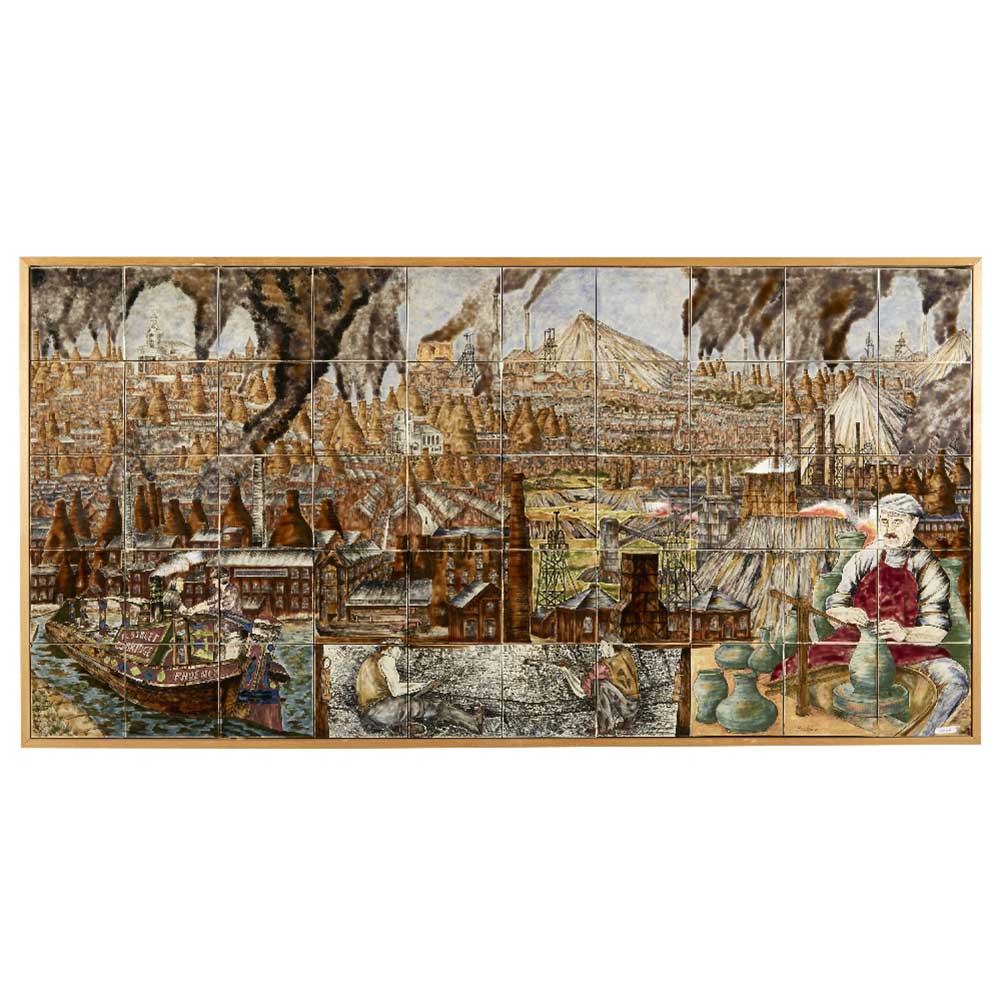

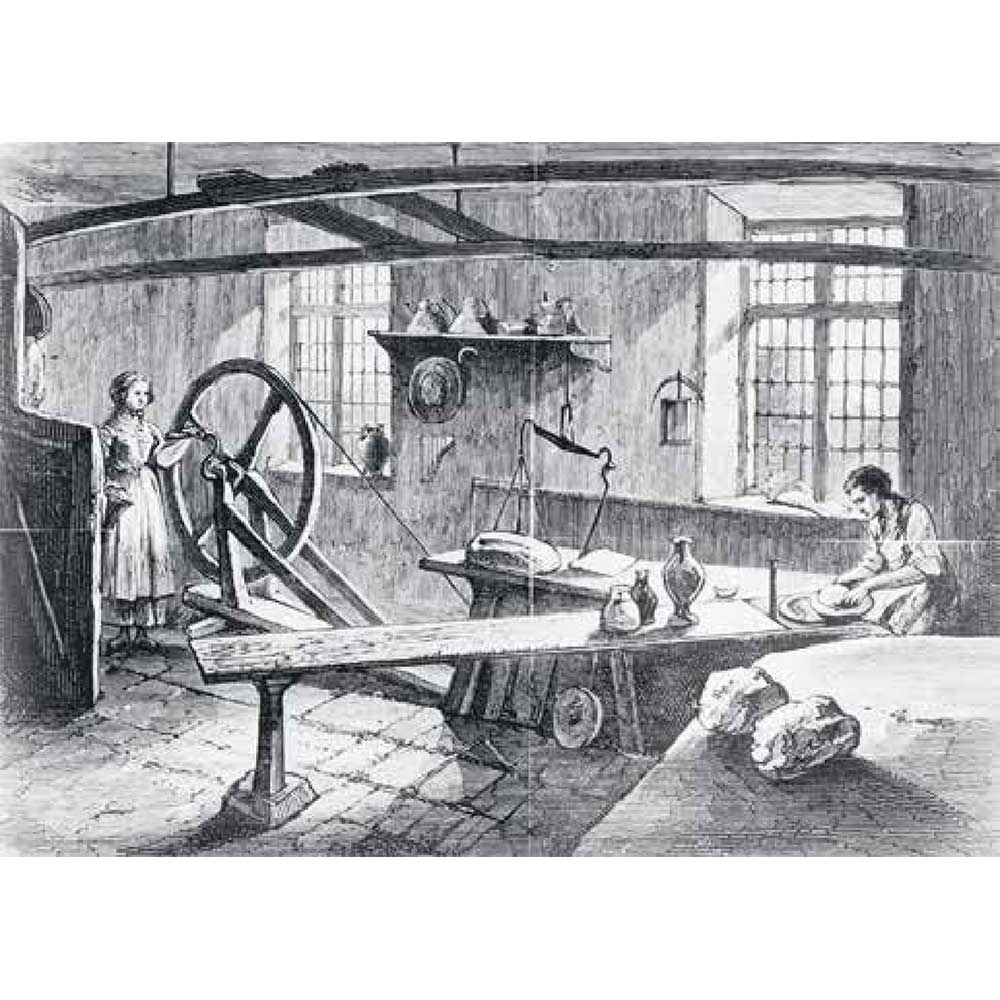

After Henry Doulton established his Burslem factory in Stoke-on-Trent in 1877, he wrote, “In Staffordshire, I have seen women and young girls employed in the most coarse and degrading labour such as turning the wheels, wedging the clay etc.” Traditionally, in the Potteries women worked as menial assistants to their husbands and fathers, doing strenuous work for 8 to 10 hours a day. Only boys could be apprenticed to learn the trade. As the factory system developed, women worked on semi-skilled repetitive tasks, such as slip-casting, and transfer printing to decorate tableware and toilet ware. Girls as young as nine years old worked with toxic materials in abominable conditions, vulnerable to lung disease, known as “potter’s rot”, and lead poisoning, which caused miscarriages. At the beginning of the 20th century, women represented nearly half the workforce in the Stoke-on-Trent potteries. However, men tenaciously guarded their positions as painters and gilders and even prevented women from using gold and armrests so that they could not do the fine, lucrative work.

Firing Miss Daisy

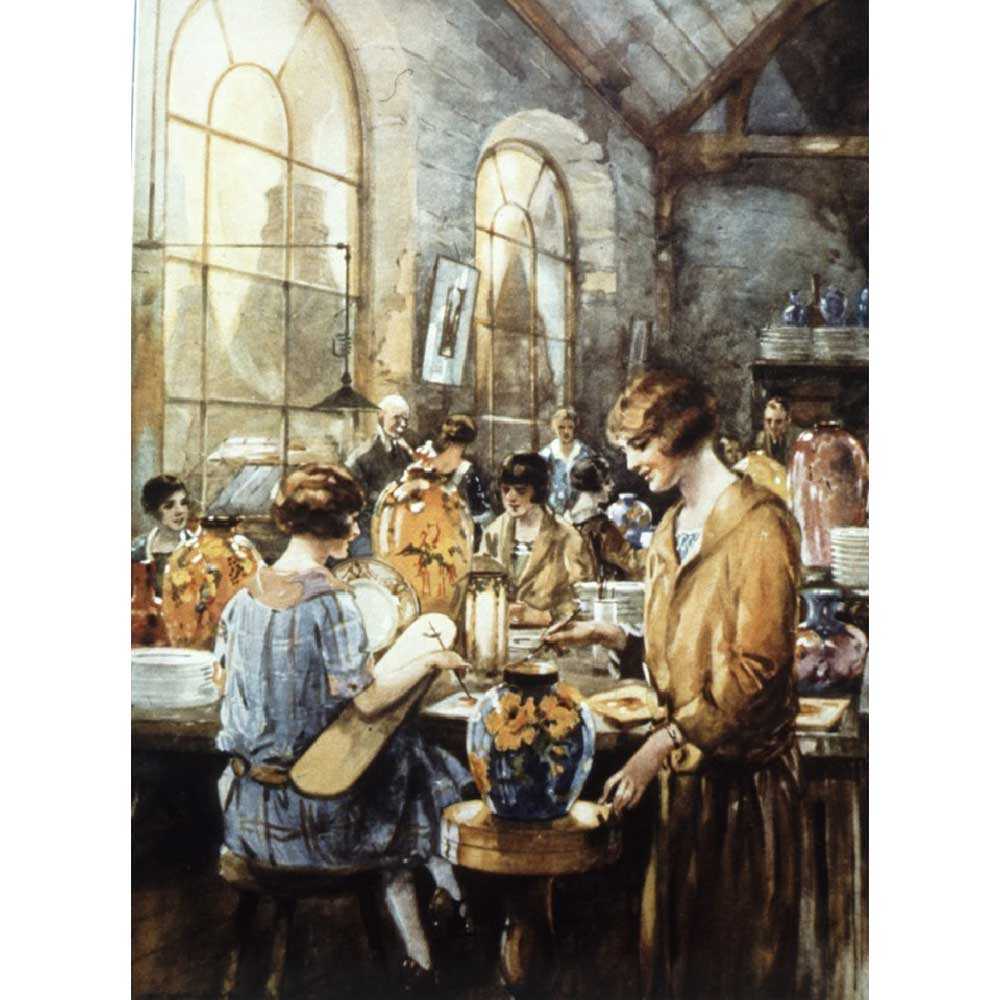

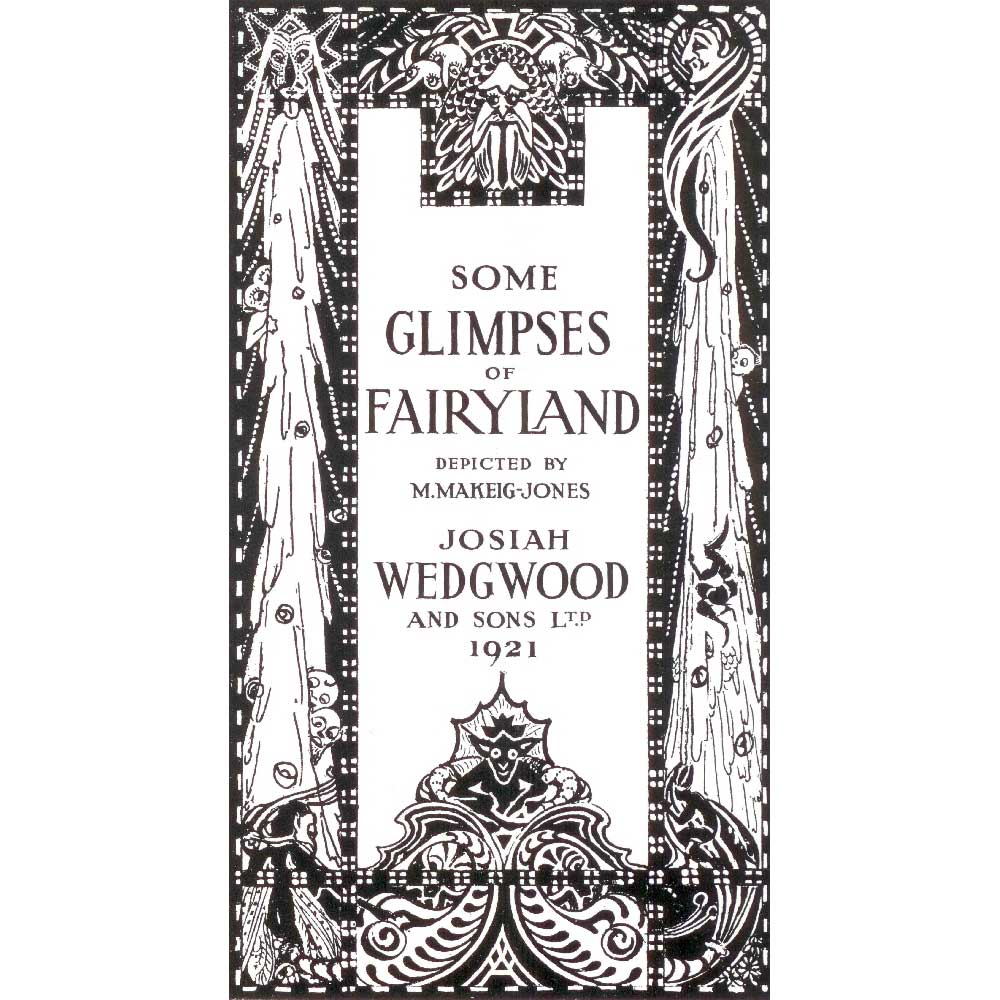

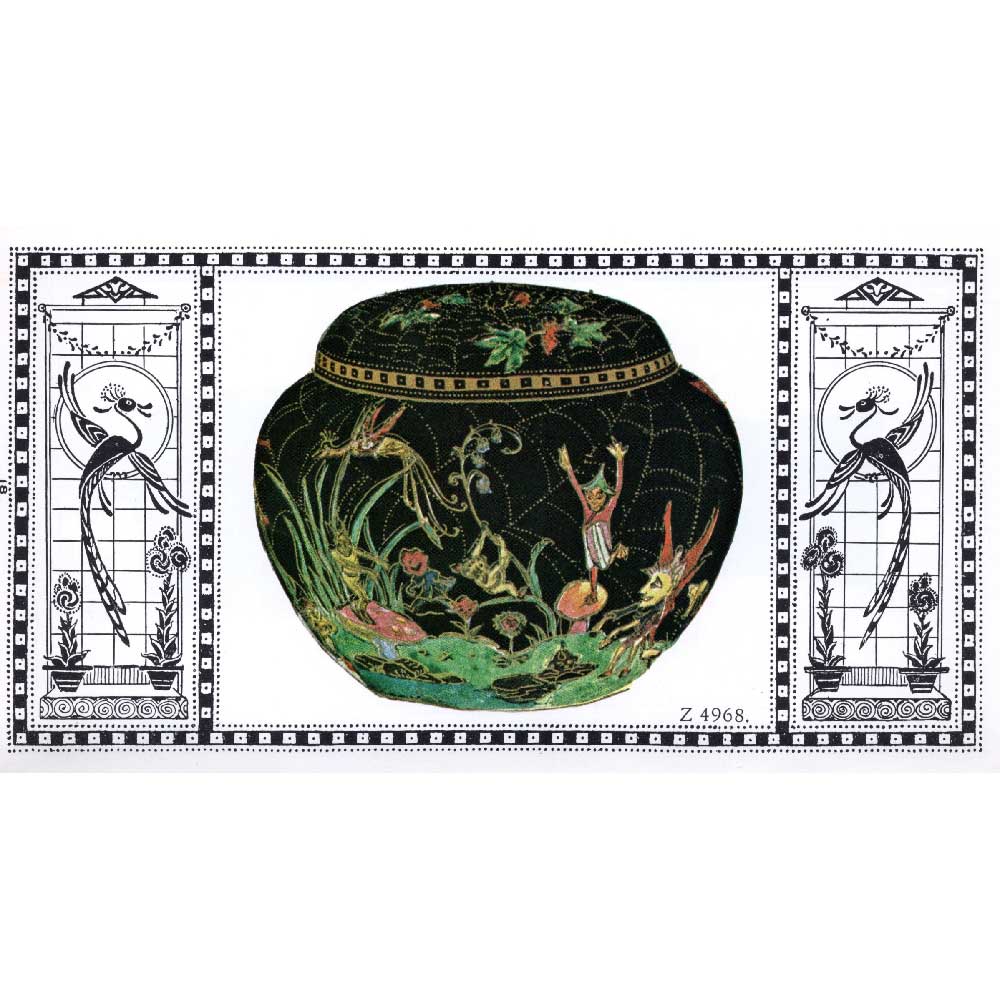

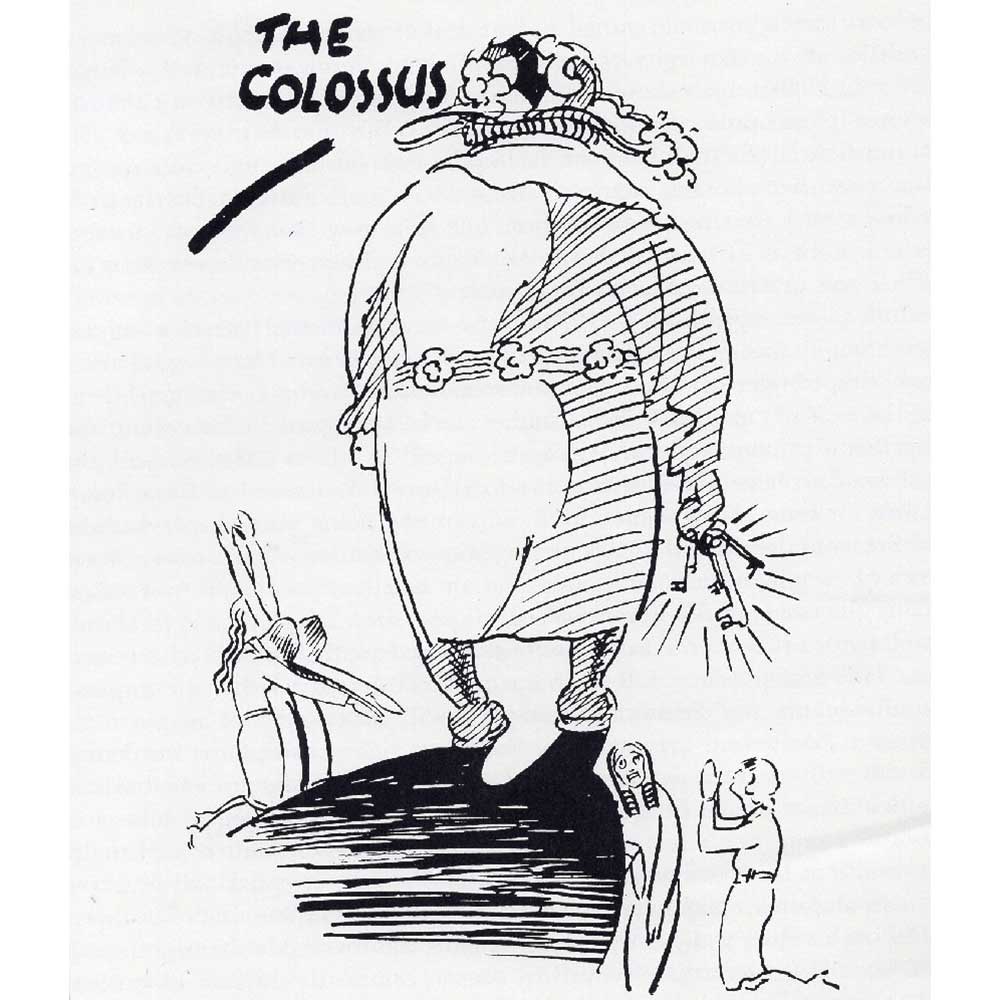

During World War I, Wedgwood’s Fairyland Lustre ware became very successful in the luxury market. Wealthy customers could escape into a fantasy world of gilded forests and gardens populated with pixies and elves, created by Miss Daisy Makeig-Jones. Daisy’s ambition to be a designer took her from Torquay Art School to the Potteries, where family friends secured her a job at Wedgwood in 1911. However, first she had to learn to be a paintress on the shop floor before becoming a designer. Fairyland Lustre ware continued to dazzle during the roaring twenties, but sales waned after the Wall Street Crash of 1929 heralded the Great Depression. Daisy was fired by Wedgwood but refused to leave the factory until after a huge row when she arranged for all her work to be smashed in her studio.

The Sunshine Girl

One of the greatest success stories of the Depression-era in Stoke-on-Trent was the career of Miss Clarice Cliff. She was born into a large family in 1899 and started work as a painter at a local pottery at the age of 13. At the same time, she attended evening classes at the Tunstall School of Art before joining the Wilkinson factory as a lithographer on her 17th birthday. Clarice soon impressed the management and became romantically involved with the owner Colley Shorter, an older married man. He arranged for Clarice to attend sculpture classes at the Royal College of Art in London where she was introduced to the latest design trends in Europe.

Clarice returned to her own studio at Wilkinson’s and her Bizarre Ware was launched in 1927. These exuberant designs were hand-painted in vivid colors by a few girls and immediately captured the attention of the British public. Clarice was acclaimed as the Sunshine Girl for overcoming the drab, greyness of their post-war surroundings. Within a year, Wilkinson’s entire Newport pottery was given over to Bizarre ware with hundreds of girls painting the abstract Cubist patterns on radical angular shapes. Her decorating girls gave in-store demonstrations wearing artist’s smocks and photo opportunities showed Clarice taking tea with celebrities of the day. The publicity that Clarice received in the national press was unprecedented. The public was fascinated by this new career woman of the 1930s, one of the first female art directors in the pottery industry and one of the first to brand her work.

Louise Irvine has written a series of articles about women in the pottery industry for Arts & Crafts Tours, a luxury tour company which specializes in personalized tours that combine luxury with learning. They will be exploring Women of the Arts and Crafts Movement in Britain from September 18-26, 2021. Arts & Crafts Tours

Read more about Victorian Women

Women's Day

Read more about Women’s Suffrage

Votes for Women

Read more about Daisy Makeig-Jones

Daisy's Dark Side

Read more about Clarice Cliff

A Bizarre Affair

Read about women’s achievements as designers and muses

Flappers, Vamps & Divas

“Deeds Not Words” London Suffragettes Meeting

Doulton Votes for Women Inkwell

Doulton Votes for Women Inkwell

Doulton Votes for Women Inkwell

Doulton Votes for Women Inkwell

Women Picketing in front of the White House

Votes for Women Cartoon

Votes for Women Cartoon

Votes for Women Cartoon

The Proposal Cartoon

Suffragette Cartoon

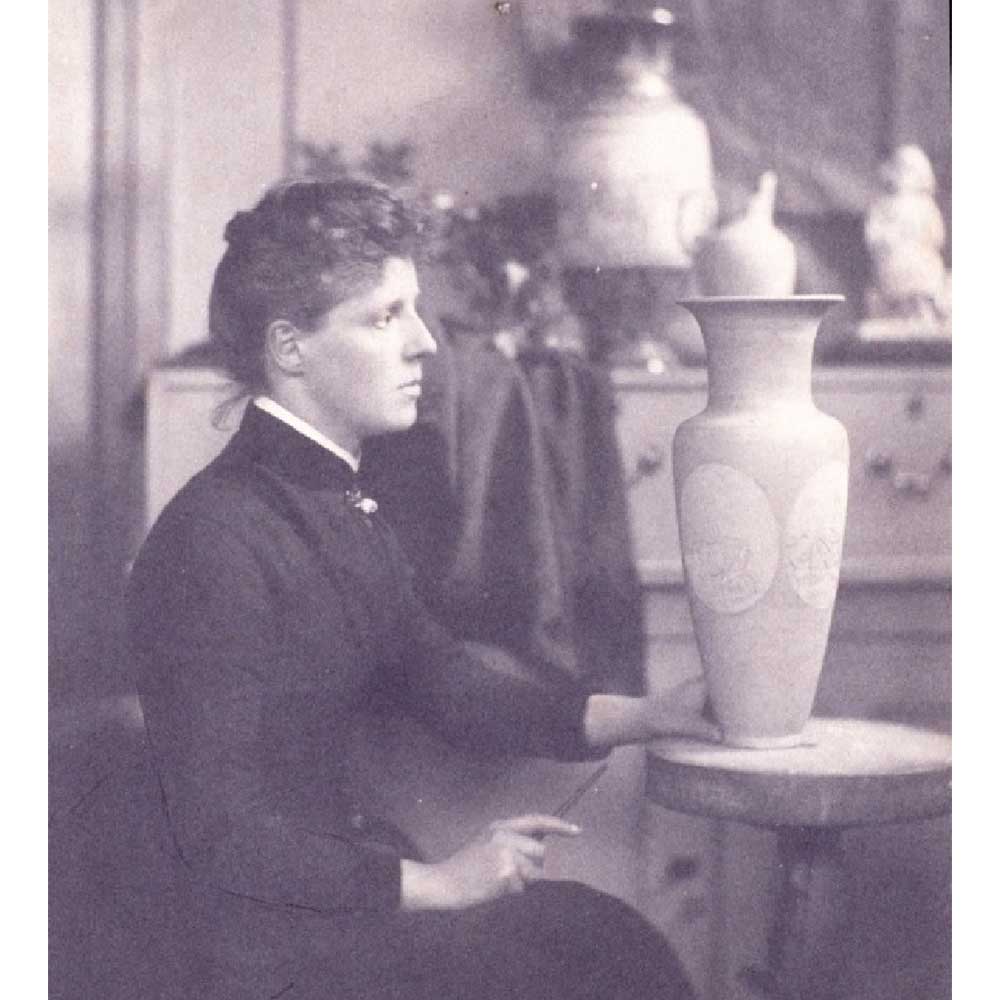

Porcelain Collector by A. Stevens

My Aesthetic Love

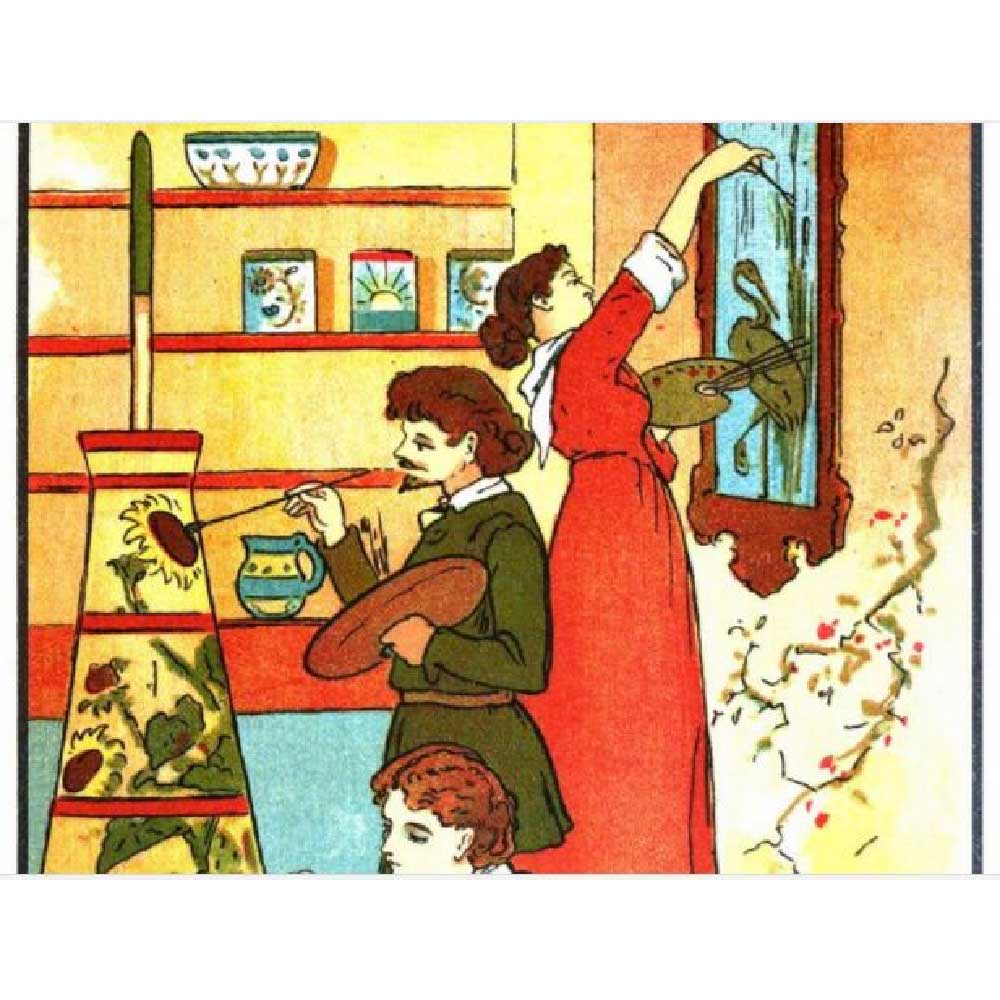

Doulton Women at Work

China Painting Book 1883 by F. Lewis

Henry Doulton

Women painting Faience at Doulton

Women at V&A painting Grill Room Tiles

The Potter's Daughter by W. S. Coleman

Florence Lewis

Doulton Presentation Volume 1882

Doulton Presentation Volume 1882

Doulton Lambeth Studio Artists

Doulton Decorators Leisure Hour 1885 by A. Dennis

Miss Barlow at Work

The Decorative Sisters : A Modern Ballad 1881

View of Stoke-on-Trent in smoke

Potteries Tile Panel by P. Gibson

Woman turning the potter’s wheel

Doulton Women at Work

Enamel Preparation

Doulton Burslem Women at Work

Doulton Women C. E. Turner

Decorating fine bone china in enamel colors

Daisy Makeig Jones

Wedgwood Factory with Daisy's Studio

Fairyland Lustre Catalog

Fairyland Lustre Catalog Page

Fairyland Lustre Catalog Page

Fairyland Lustre Catalog Page

Daisy Makeig Jones cartoon

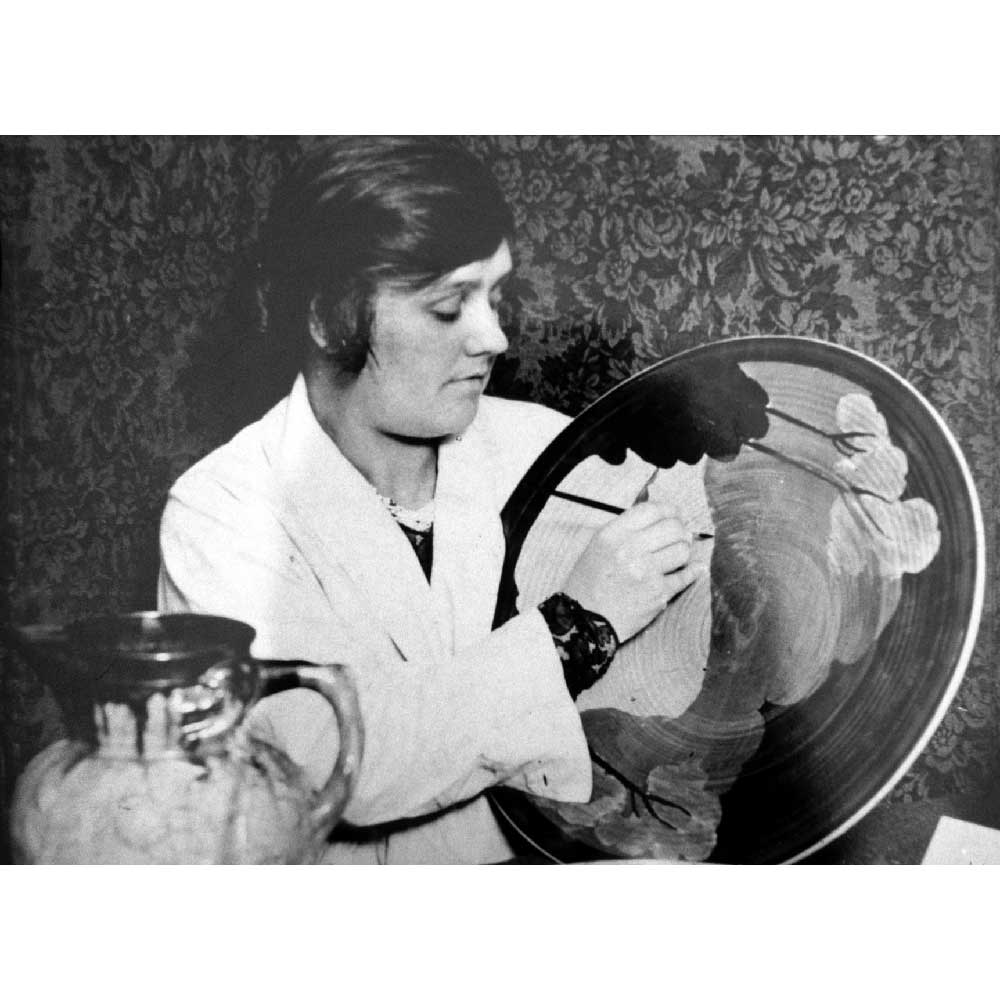

Clarice Cliff at work

House and Trees Charger by C. Cliff

Clarice Cliff detail

Clarice Cliff girls

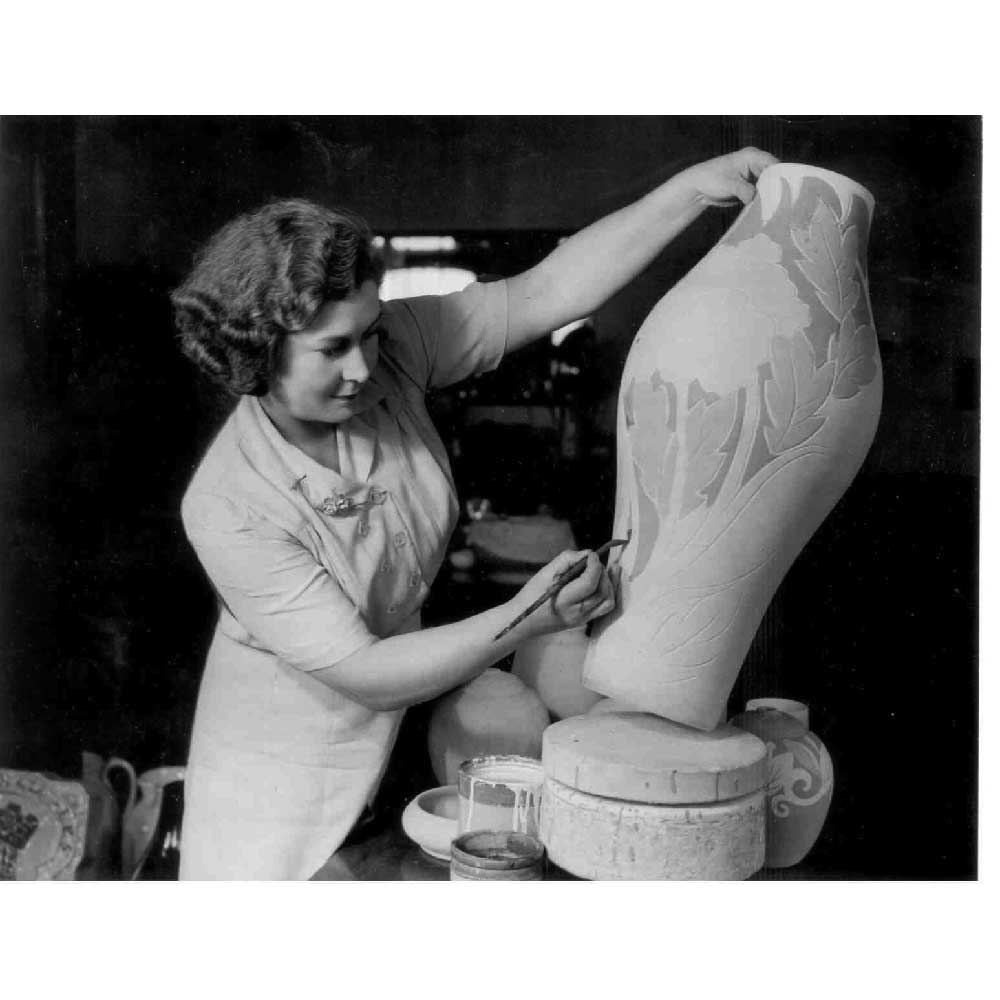

Vera Huggins working at Doulton’s Lambeth Studio

Louise Irvine