By Louise Irvine

Victorian ladies used flowers as a means of covert communication and a Language of Flowers bloomed alongside a growing interest in botany among women. Flower gardening was considered appropriate for feminine sensibilities and women laid out flower gardens or tended potted plants in their parlors. 19th-century potteries responded with an abundance of fashionable ceramic vessels for use in gardens and conservatories. In elegant homes, ornamental flowerpots and plant stands were called jardinières from the French word for a female gardener.

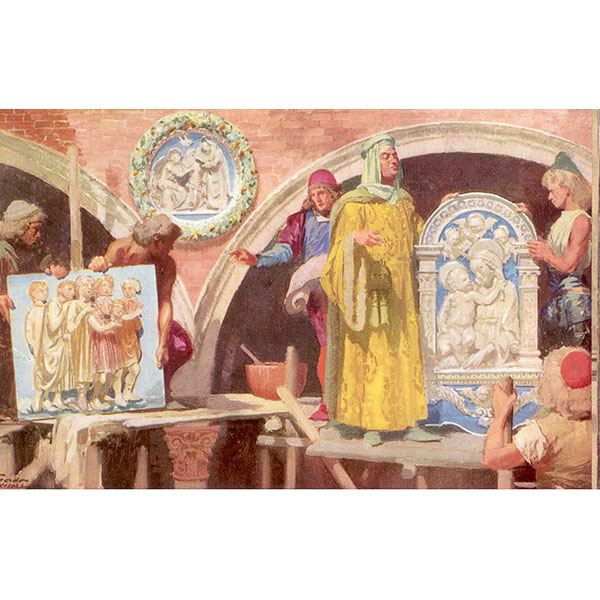

For centuries, wealthy Europeans decorated their country estates with garden pots made by Italian craftsmen in terracotta, literally meaning “cooked earth”. The Della Robbia family were famous for adding color to their glazed terracotta sculptures in 15th century Florence. It is said that the Italian Capodimonte porcelain factory flourished in the 18th century because King Charles VII’s allergies prevented him from enjoying nature’s fleeting beauty so he directed his workshop to produce permanent porcelain flower arrangements for the royal palace.

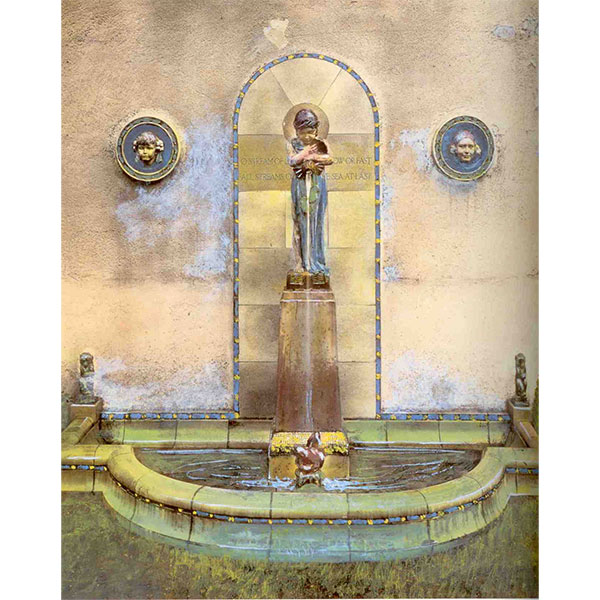

In France, Bernard Palissy’s experiments to produce porcelain during the 1540s resulted in his Rustic ware, which featured realistic animals crawling through vegetation. Apparently, Palissy and his family were reduced to poverty for many years during his pottery experiments and he burned their furniture and floorboards to feed the fires of his furnaces! Fortunately, he was discovered by Queen Catherine des Medicis who commissioned him to create gardens with ceramic grottoes in Paris. The passion of Palissy, Della Robbia, and other pioneering potters inspired Victorian entrepreneurs, notably Herbert Minton and Henry Doulton, to emulate the vividly colored glaze effects

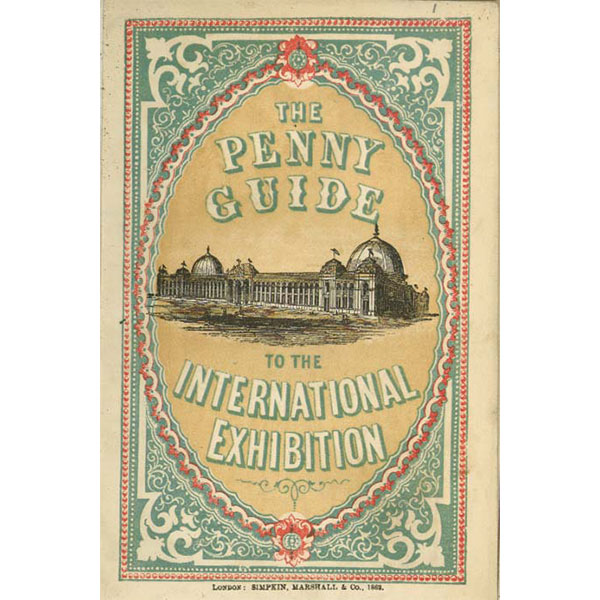

Palissy’s lead-glazed ceramics sowed the seeds for Minton’s Palissy Ware which was launched at the Great Exhibition of 1851 held in the Crystal Palace, London. The new ceramics soon became better known as Majolica ware after Italian Maiolica and was produced by countless factories in the UK and the USA as can be seen in the new Majolica Mania exhibition at the Bard Graduate Center in New York. Majolica jardinières reflected all the popular styles of the era from formal classical motifs of the High Renaissance style to naturalistic renderings of flora and fauna.

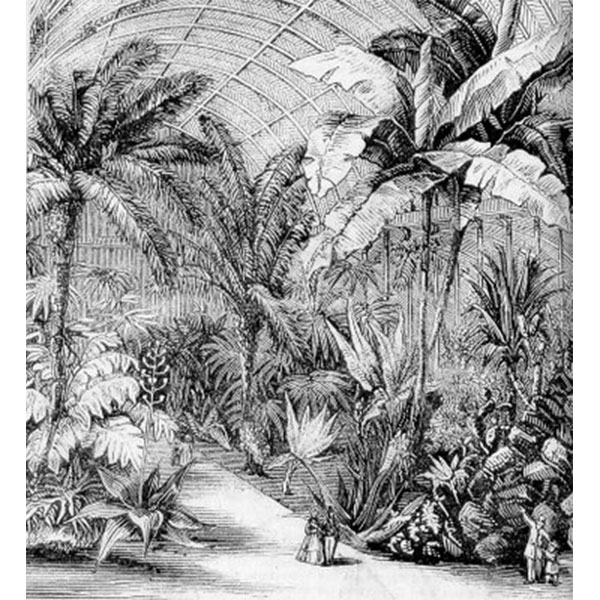

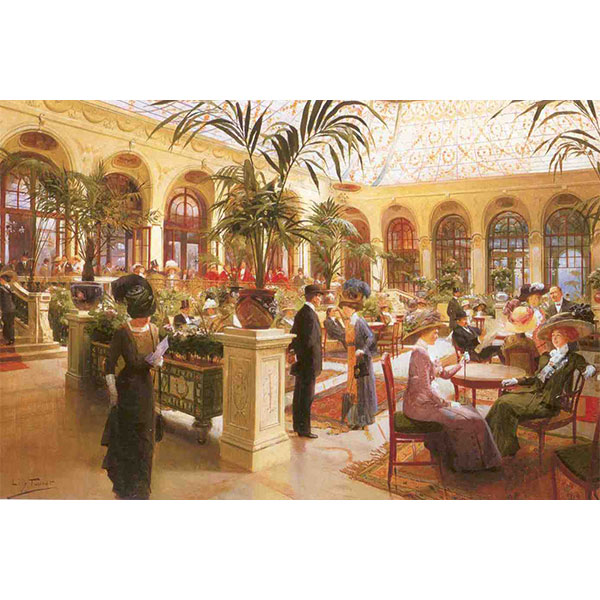

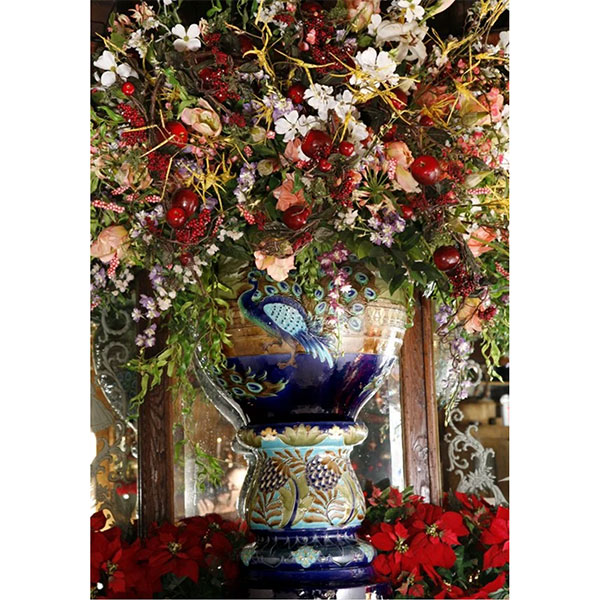

At WMODA, we have Minton designs in brilliant turquoise and pink glazes depicting putti cavorting with floral garlands. George Jones offered deep midnight blue and turquoise jardinières embellished with birds in foliage. Some had matching drip trays for tabletop display of the live plants or flower arrangements while others had monumental pedestals. Portable Majolica seats were also available so that the ladies could rest while dabbling in gardening or receiving guests. Artfully positioned in the foliage were Majolica garden statues of animals and birds or perhaps a playing fountain. Elegantly furnished conservatories were used for entertaining, taking afternoon tea, and even accepting a proposal of marriage.

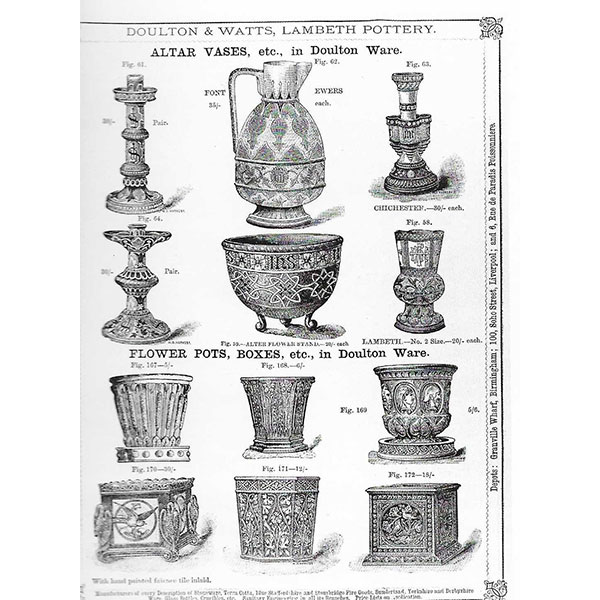

The Doulton version of Victorian Majolica ware was introduced later in the 19th century and was called Modeled Faience in the trade catalogs although contemporary writers refer to it as Majolica. It was used for interior architectural features, such as fireplaces, as well as jardinières, flowerpots, and conservatory furniture. The Doulton Lambeth Potteries also made a colorful stoneware body that could withstand frost and dampness and was suitable for outdoor use in northern gardens. The earthy salt-glaze stoneware body became known as Doulton ware and the more vibrantly colored body was called Polychrome Stoneware.

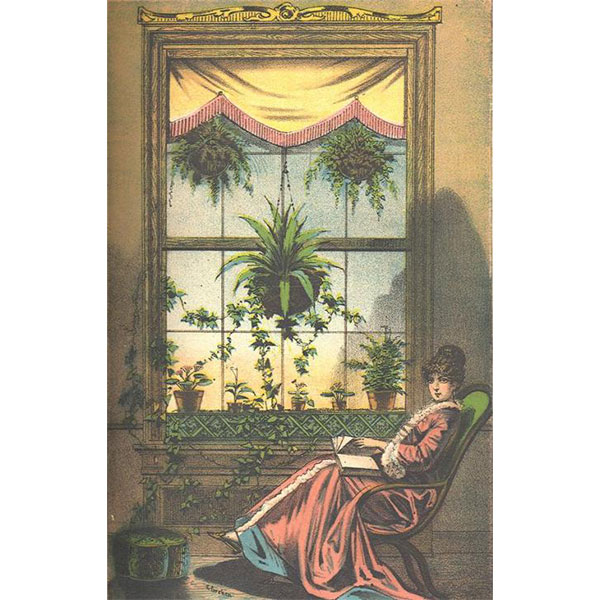

During the 19th century, the aristocracy vied with each other in the creation of their own “Crystal Palaces” as status symbols. They measured wealth and taste in the size of their flower gardens and conservatories for tender exotic plants. Later in the century, the middle classes aspired to their own glazed oasis attached to their home, made available by advances in glass manufacture, cast-iron, and hot-water piping. Even if a conservatory was out of reach, the lady of the house could still indulge in window gardening and flower arranging in vases and jardinières. Floral arrangements were often used to send coded messages, allowing the sender to express unspoken feelings. Armed with an abundance of floral dictionaries for the Language of Flowers, Victorians often gave small "talking bouquets" called tussie-mussies to their Valentines.

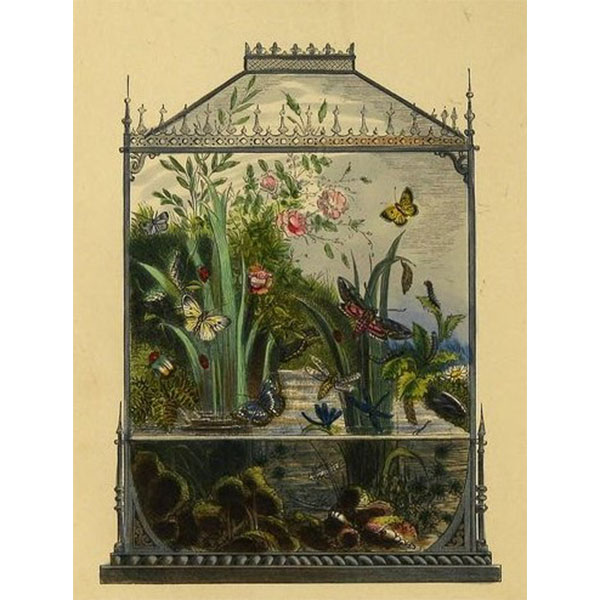

Flowers embellished everything in the Victorian home from the wallpaper to the carpet to the art pottery. This sanctuary of nature reflected the resident’s interest in natural history as well as gardening. The décor might include shells, butterflies, stuffed birds, and peacock feathers as well as potted palms in profusion. Some affluent homes even had a vivarium or terrarium where they could watch live insects. Carnivorous plants presented a somewhat macabre spectator sport behind glass!

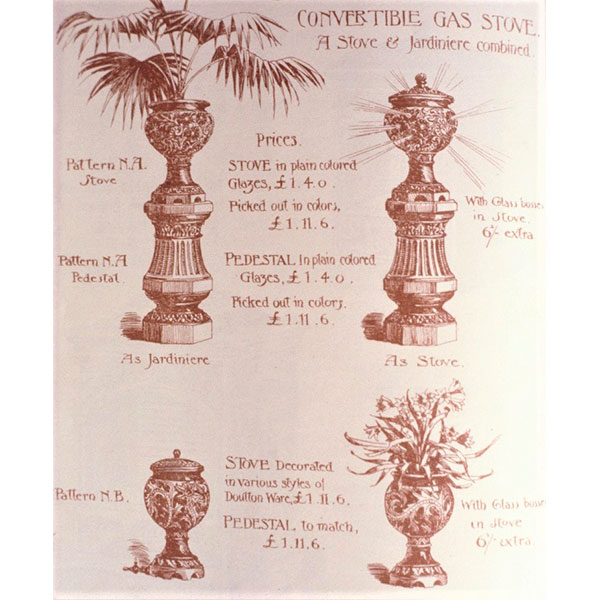

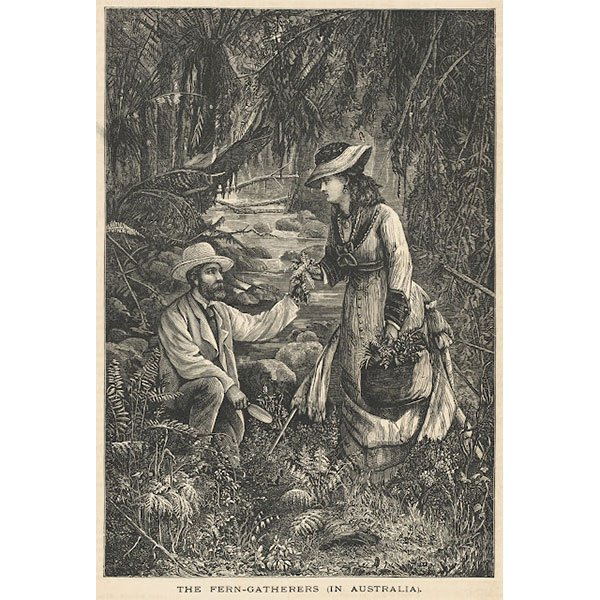

Ferns were one of the favorite plants for ladies to cultivate indoors and were supplied by plant tinkers or botany bens who gathered them wild and hawked them door to door. Even better, ladies with fern fever could go plant hunting as healthy exercise. The ferns thrived in a Wardian case, which was invented by Dr. Nathaniel Ward to transport plants from overseas. They were valued for domestic use as they protected plants from the noxious fumes generated by gas lights and coal fires. The Doulton Potteries made ceramic bases for Wardian cases so that ladies could garden under glass in style. They also offered a rather bizarre invention which was a gas stove and jardinière combined. Presumably, it was used as a stove in the winter and a plant holder in the summer or the aspidistra plants would get frazzled!

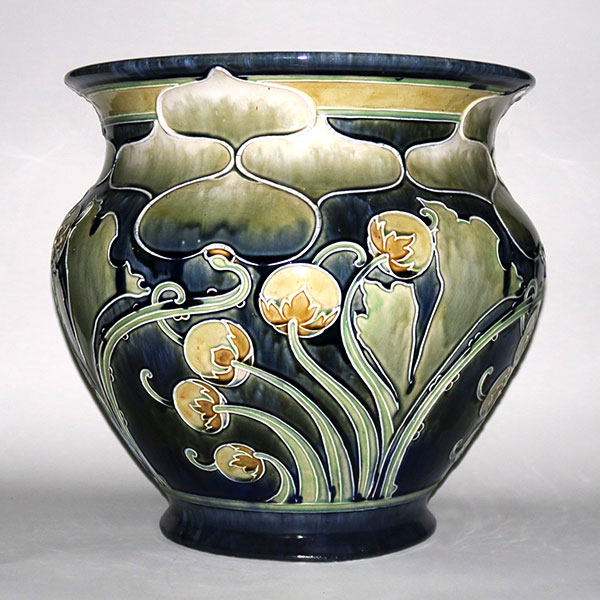

The popularity of Majolica wares waned in the early 1900s but flowerpots and jardinières remained popular in other ceramic bodies. Indian style jardinières and furniture were made in Doulton’s Modeled Faience to create an exotic setting for the orchids and other foreign plants which flourished in heated conservatories. As the Art Nouveau style took root in ceramics, the Royal Doulton trade catalogs were full of curvaceous stoneware forms inspired by nature’s bounty. Many were designed by their leading artists, notably Mark V. Marshall a master of the swirling, sinuous style in stoneware that can be seen in all the striking examples at WMODA. One of his monumental jardinières made it all the way to India where it can still be seen today in the Maharaja’s Palace in Baroda.

Swans and peacocks were popular design motifs during the Art Nouveau era and WMODA has stunning examples by the Burmantoft and Dressler factories. The modern Moorcroft art pottery studio revived this style as can be seen in the design inspired by William Morris at WMODA. Recently, the Ardmore studio in South Africa turned their attention to flowerpots and ceramic art for the garden and have sent us some beautiful photographs of their garden with bird feeders, visiting insects, and stunning sculptures of ferns and flowers which will never fade. Thanks to the talents of the Ardmore artists, their new African garden will be blooming forever.

Read More...

Flower Arranging G. Rossetti detail

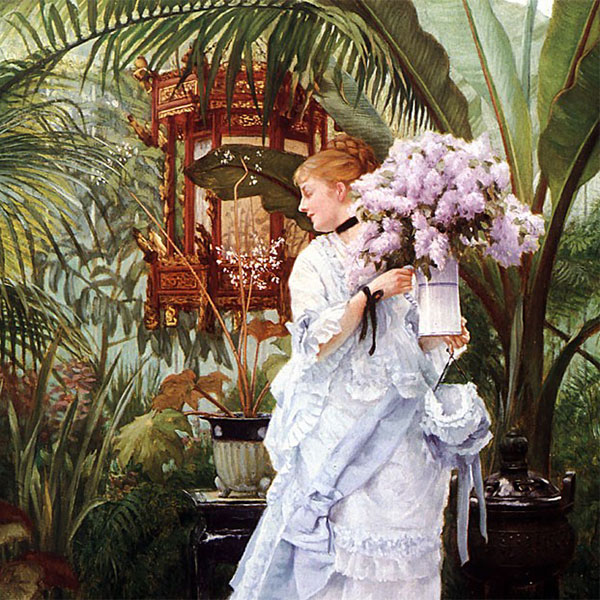

The Bunch of Lilacs by J. Tissot detail

Della Robbia by G. Nicoll

Della Robbia tile panel by J. Eyre for Doulton Lambeth

Doulton Terracotta Modeler

Bernard Palissy plaque by J. Eyre for Doulton Lambeth

Mafra Palissy Style Plaque

Mafra Palissy Style Plaque

Mafra Palissy Style Plaque

Majolica @ WMODA

Minton Majolica Stork

Minton Majolica Crane Jardinière

Penny Guide to the Great Exhibition

Minton display at the Great Exhibition

Chatsworth Conservatory

Minton Majolica Putti Jardinière

Minton Majolica Jardinière with Faun handles

Minton Majolica Jardinière with snake handles

Minton Majolica Swan Jardinière

George Jones Majolica Jardinière

George Jones Majolica Jardinière and Tray

George Jones Majolica Jardinière and Tray

George Jones Majolica Garden Seat

George Jones Majolica Garden Seat

George Jones Majolica Jardinière

George Jones Majolica Jardinière

Wedgwood Majolica Jardinière

Wedgwood Majolica Jardinière

Doulton Garden Pedestals

Doulton Jardinière and Pedestal

Doulton Indian Vase

Doulton Indian Pierced Table

Doulton Indian Table Top

Doulton Indian Pedestal and Jardinière

Doulton Gas Stove & Jardinière

Doulton Jardinière and Pedestal

Vivarium

Window gardening

New Practical Window Gardener by J. Mollison

Window gardening Wardian Cases

Fern Gathering Australia

Royal Doulton Art Nouveau Foliate Jardinière

Jardinière detail

Royal Doulton Art Nouveau Foliate Jardinière

Marshall Jardinière Harriman Judd Collection

Royal Doulton Jardinière by M.V. Marshall

Jardinière detail

Royal Doulton Jardinière by M.V. Marshall

Doulton Ware Catalog

Cafe de la Paix by Fauret

Royal Doulton Polychrome Stoneware Design by G. Bayes

Watercolor of Doulton Jardinière design H. Simeon

Gilbert Bayes Garden at the Doulton Story, V & A

Maharaja Palace Baroda with a Doulton Jardinière

Burmantofts Jardinière at the Tavern on the Green New York

Burmantofts Peacock Jardinière

Burmantoft & Dressler Jardinières @ WMODA

Julius Dressler Jardinière

Moorcroft Hartgring Jardinière

Moorcroft Tree Bark Thief Jardinière

Moorcroft Tree Bark Thief Jardinière @ WMODA

Ardmore Outdoors Collection

Ardmore Outdoors Collection

Ardmore Outdoors Collection

Ardmore Outdoors Collection

Ardmore Outdoors Collection

Ardmore Outdoors Collection

Ardmore Outdoors Collection

Ardmore Outdoors Collection

Ardmore Outdoors Collection