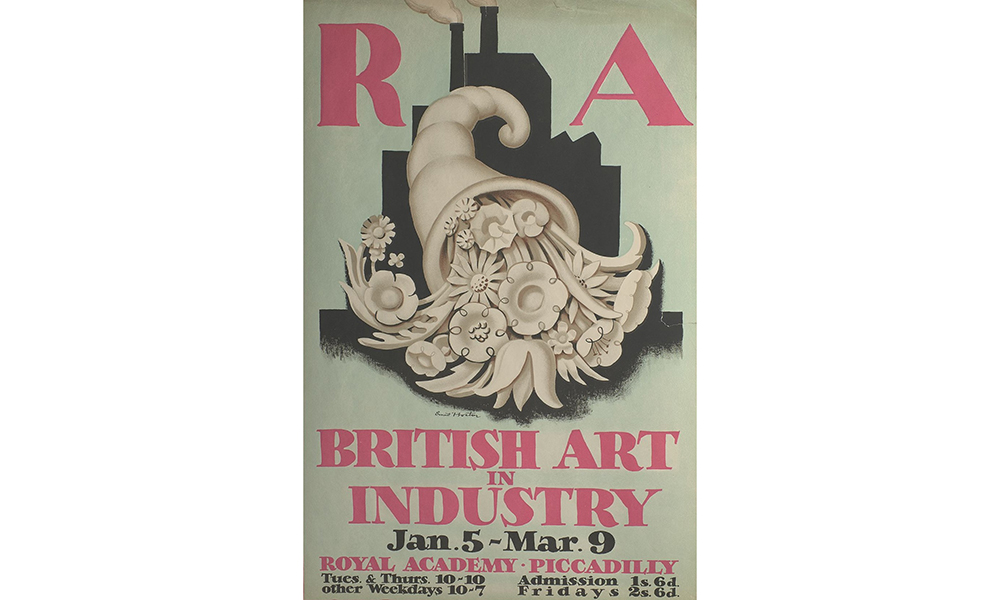

“Art in Industry” was the slogan of the 1930s when leading British pottery manufacturers sought to involve distinguished artists in their designs for tableware and fancy goods. Clarice Cliff was at the forefront of this movement, having been chosen as the Art Director for an exhibition of Modern Art for the Table at Harrods, showcasing 28 artists. One of the best-known was Sir Frank Brangwyn whose controversial British Empire murals inspired limited edition plaques which were hand-painted in Clarice Cliff’s studio.

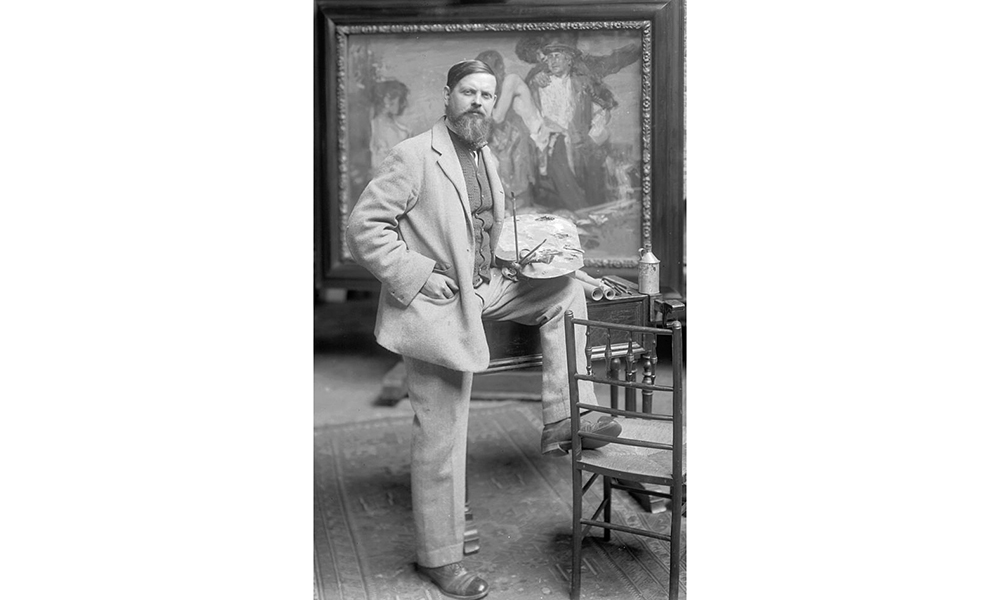

Frank Brangwyn (1867-1956) was one of the most prolific and versatile artists of the 20th century. At the age of 15, he trained as a draughtsman with William Morris and learned to work in a variety of media. He traveled extensively and received numerous international commissions and honors. His work ranged from large-scale murals to applied arts, including ceramics. It is estimated that Brangwyn produced over 12,000 works during his lifetime, and he was knighted for his achievements in 1941.

-

Clarice Cliff Plaques after Frank Brangwyn

-

Clarice Cliff Plaque after Frank Brangwyn

-

Clarice Cliff Plaque after Frank Brangwyn

-

Clarice Cliff

-

Frank Brangwyn

-

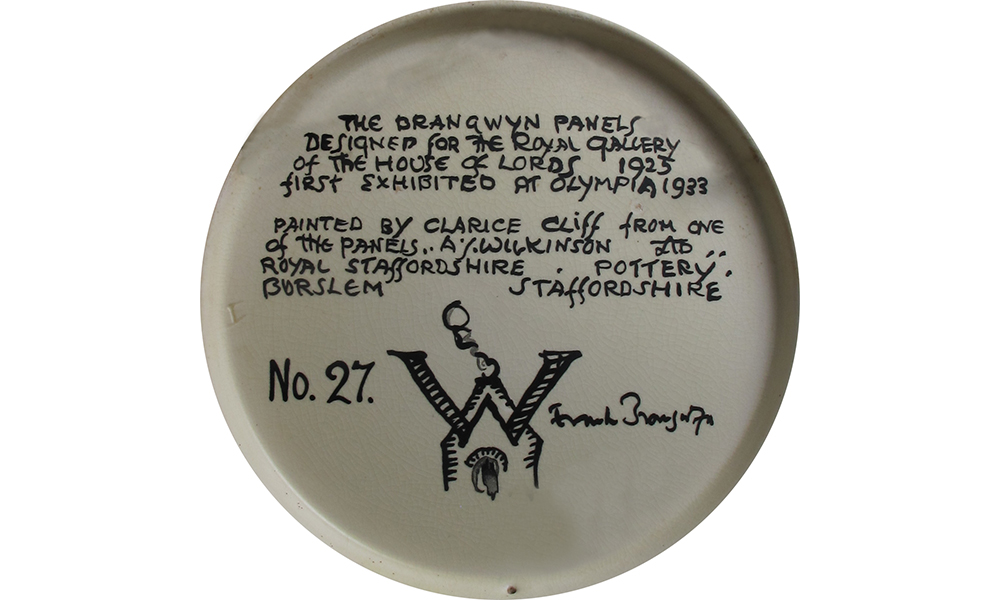

Back of India Plaque

In 1924, Brangwyn’s Pageant was featured in the souvenir catalog of the British Empire Exhibition at Wembley in London. He was at the height of his fame and considered the obvious choice to paint murals for the Royal Gallery in the Palace of Westminster, commemorating members of the House of Lords and their families who lost their lives in the First World War. Brangwyn’s first concept for the vast commission, around 3,000 square feet, was to paint soldiers in action, but the initial panels were considered too brutal a reminder of the conflict.

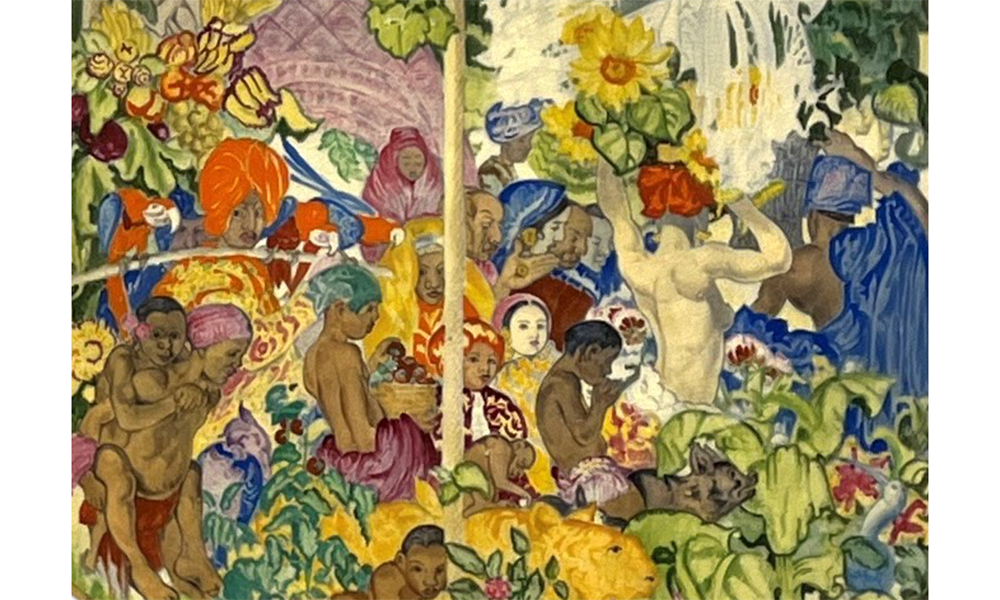

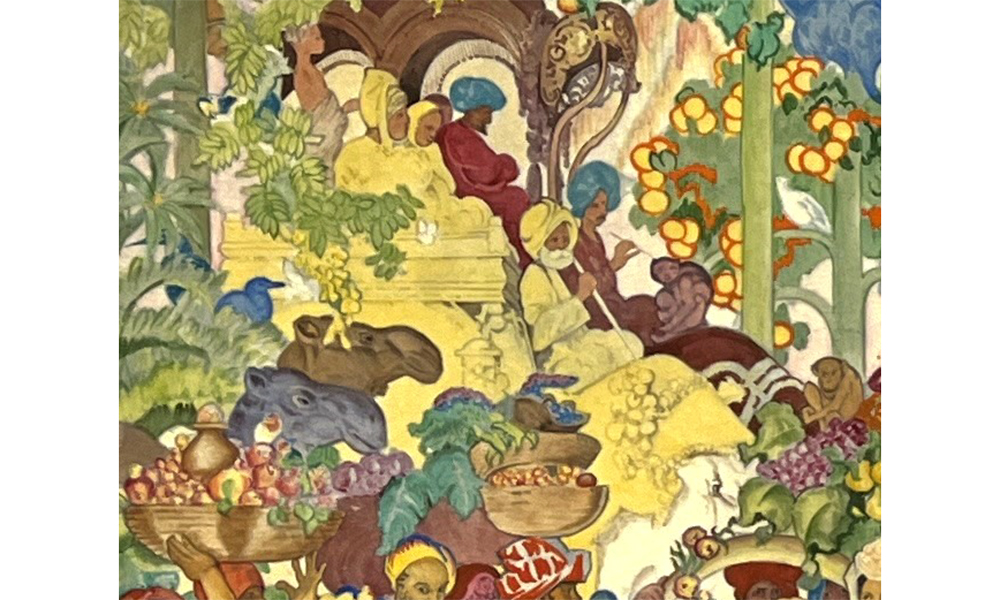

Brangwyn settled on a series of decorative paintings celebrating the natural beauty and resources of the British Empire, for which men had been fighting. It was his vision of an eternal paradise where the sun never sets. Unfortunately, only five of the 16 proposed panels had been completed when Lord Iveagh, Brangwyn’s patron and principal supporter, died in 1927. The Fine Art Commission and the House of Lords rejected the lively, exotic scenes as unsuitable for their conservative historic surroundings. The most vocal critics derided the nakedness and bananas, which they felt were more appropriate for a nightclub.

-

The Pageant by Brangwyn for the British Empire Exhibition Catalog

-

Detail Clarice Cliff after Frank Brangwyn

-

Elephants and Camels Detail

-

British Art In Industry Catalog

For others, the exuberant paintings of tropical flora and fauna were enchanting and a reminder of the glorious beauty of nature after the atrocities of war. As the debate ensued, the panels were exhibited at the Ideal Home Exhibition in Olympia in 1933 where they caught the attention of Clarice Cliff from Wilkinson’s Royal Staffordshire Pottery. With Brangwyn’s permission, she adapted images from the India panel for two large wall plaques, 17 ½ inches in diameter. The hand-painted plaques were produced in very limited numbers and priced at 10 guineas.

At first glance, it is easy to miss the massive elephant amidst all the dense, lush vegetation. Brangwyn visited London Zoo to accurately portray the wild animals that he included in his designs. Most of the flowers and foliage are identifiable as Brangwyn also had a good knowledge of botany. He brought back exotic plants from his travels in the East to cultivate in his London garden. He worked from life drawings and photographs of the human models that he found for his commission, and they reappeared in his later works.

-

Royal Doulton Brangwyn Ware

-

Royal Doulton Harvest Vase by F. Brangwyn

-

Royal Doulton Brangwyn Ware Plate

-

Foley China Plate by F. Brangwyn

-

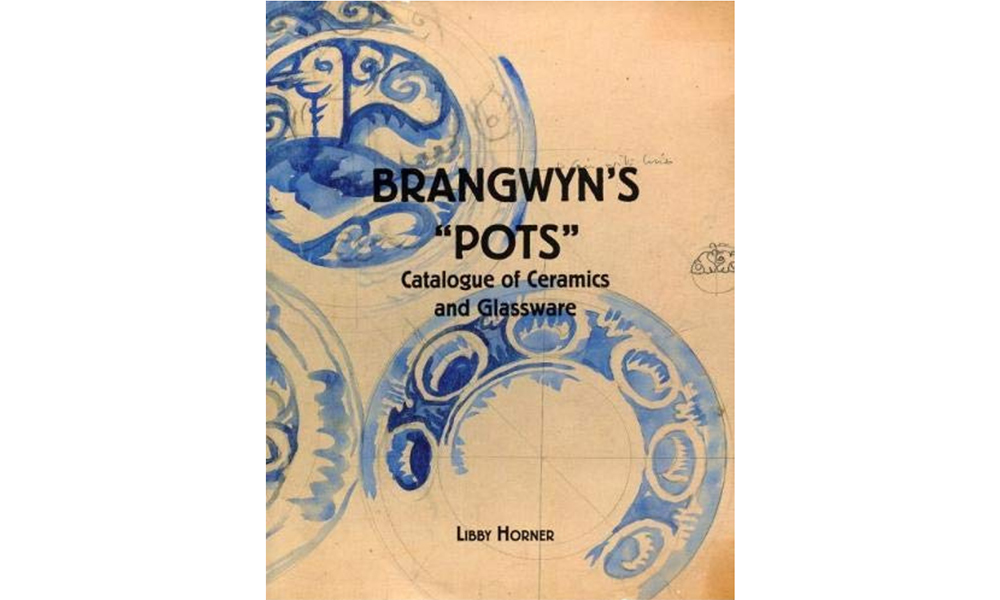

Brangwyn's Pots by L. Horner

In 1934, Brangwyn’s British Empire Panels found a permanent home in Swansea’s Guildhall, Wales where they can be seen today. Although devastated by the rejection, Brangwyn’s energies returned to his many other commissions. He was “passionate about pots” and collected Persian, Chinese and Japanese ceramics, which often appeared in his paintings. For Modern Art for the Table at Harrods, he produced an earthenware design with Clarice Cliff and a bone china design with Foley.

Several years earlier, Brangwyn had collaborated with Charles Noke at the Royal Doulton Pottery to create tableware with an earthy, hand-crafted appearance. Introduced in 1930, the buff-colored Harvest and Brangwyn patterns featured incised motifs and mottled decoration. Brangwyn wanted his Doulton designs to be “within reach of discriminating persons of moderate means,” and a dinner service for 12 cost only £8. However, it seems the public did not appreciate his efforts, as the designs did not sell well then, although they are very collectible today.