by Louise Irvine

Putti are personifications of the human spirit and emotions, including love, and are popular motifs in pottery and porcelain. Cupid, known as Eros to the Greeks, is famous today as a purveyor of love in Valentine's cards but he is just one of many cute infants who have romped through sacred and secular art. The name putto is derived from the Latin putus meaning boy and putti are depicted as chubby, naked children, often with wings. They inhabit most of the galleries at WMODA so take a closer look on your next visit.

Secular to Sacred

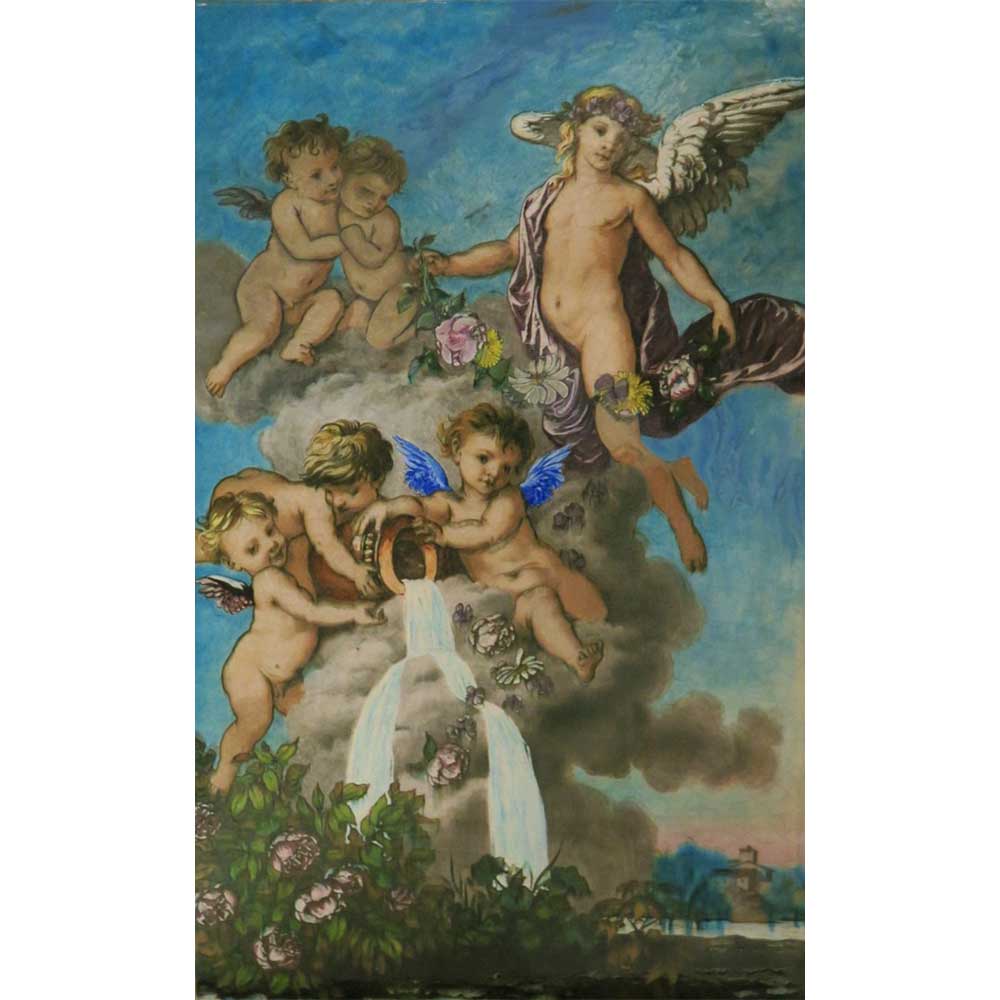

In the ancient classical world, putti were manifestations of spirits or genii, who influenced human lives. When they accompanied Aphrodite Venus, the goddess of love, they were known as Erotes or Amorini. They became closely associated with Cupid in art and hovered above dreaming lovers as harbingers of passion. As companions of Dionysius, the god of wine and ecstasy, their Bacchanalian revelry represented fertility and abundance. The woodland companions of Pan, the nature god, were known as Panisci and regularly caused panic with their mischief. Putti were often involved in behavior inappropriate for their age, drinking wine, brawling, and attacking goats, which signified lust. When riding dolphins, putti embodied the life-giving force of water. In funerary art on sarcophagi, they ushered souls to the afterlife. In Christian art, putti fluttered around the Virgin Mary, symbolizing innocence, purity and the infant Jesus. They are often referred to as cherubs, but they are not the same as the cherubim in the choirs of angels.

Classical Revival

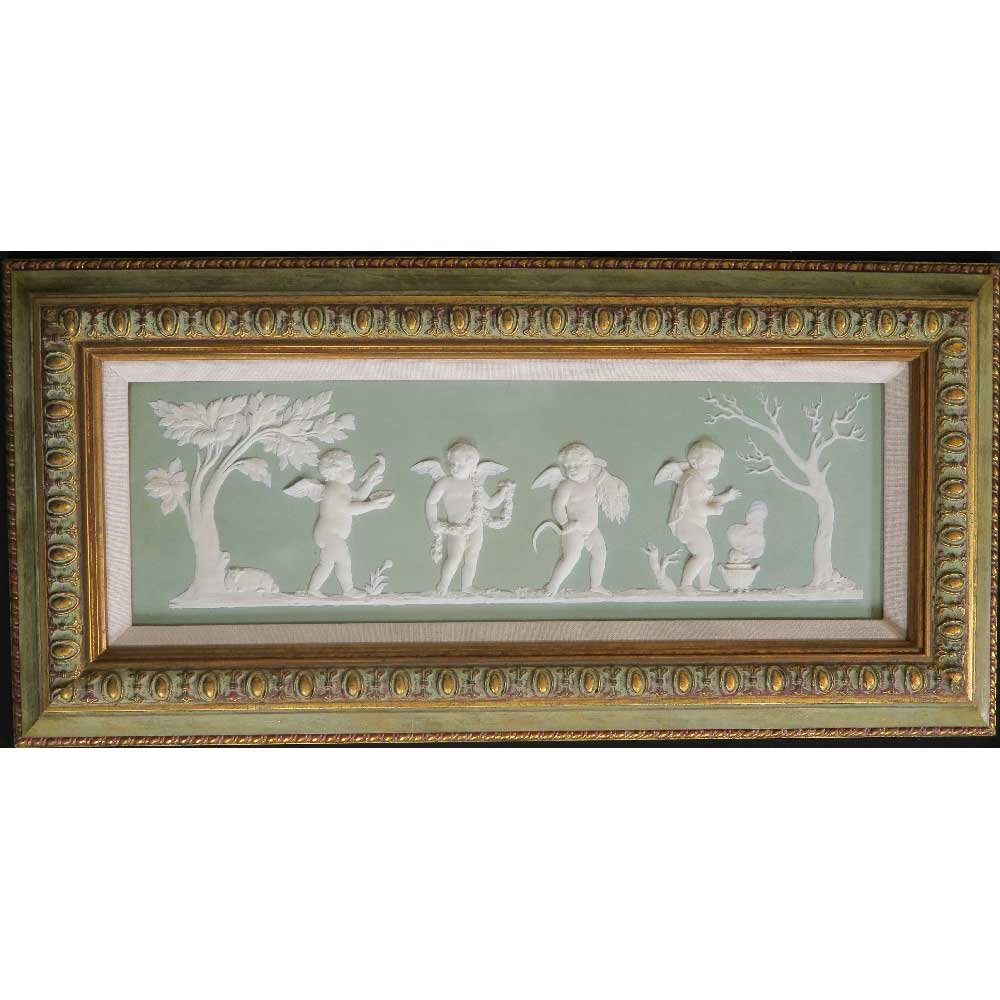

The rediscovery of the classical world in Renaissance Italy led to a revival of interest in putti and they adorned churches and public buildings, often carrying garlands of fruit and flowers or crests and scrolls. Gradually they became active participants in paintings and sculptures rather than just passive ornaments. The Baroque sculptor Francois Dusquesnoy became famous for his plump putti with carefully observed children’s heads, which inspired painters such as Rubens. One of Dusquenoy’s Bacchanalian putti sculptures features a Larvate putto wearing an ugly Silenus mask to scare his companions. It influenced Black Basalt and Jasper ware panels during the Neo-Classical revival of the 18th century.

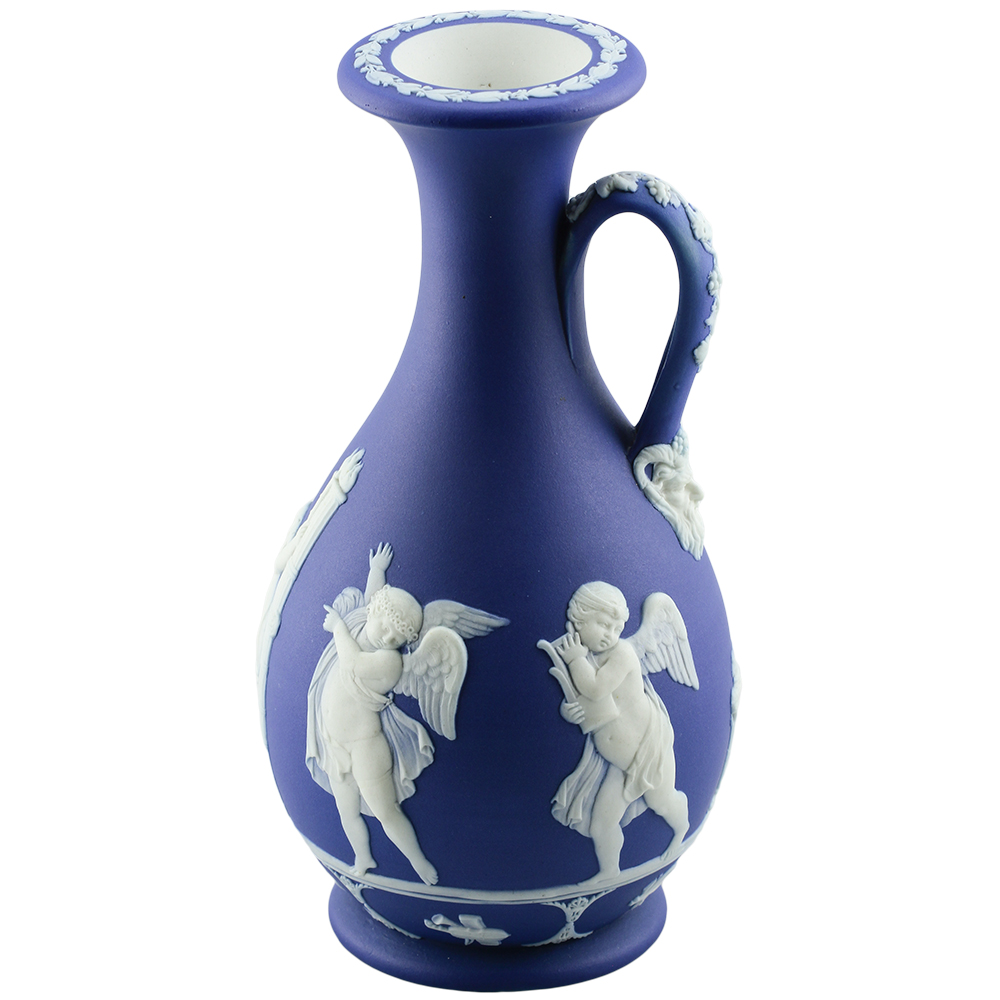

An ancient Roman cameo, known as the Marlborough gem, inspired Wedgwood’s Marriage of Cupid and Psyche, which included Aphrodite’s retinue of Erotes. The companion scene depicts the Sacrifice to Hymen, an Erotes who represented the bridal hymn sung during the wedding procession. Frolicking Bacchanalian boys were also designed by Lady Diana Beauclerk and became a popular relief decoration on Jasper ware vases, jugs and plaques.

French Rococo

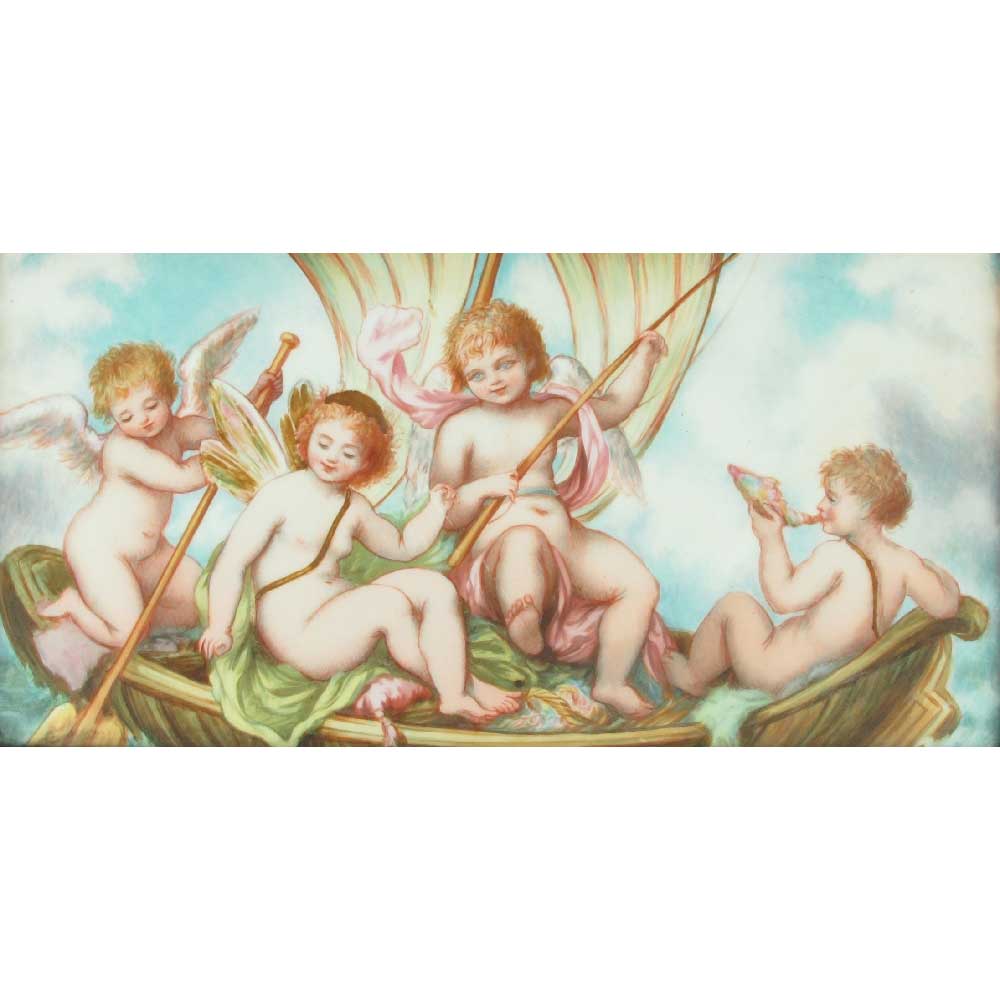

The romantic notions of the Rococo era made playful putti a popular subject in porcelain sculptures. At the Meissen factory during the 18th century, Johann Kandler sculpted lively tableaux of putti supporting classical gods and goddesses and cavorting in Bacchanalian revels. His putti are often artistic and are reminiscent of the French rococo paintings of Francois Boucher. These decorative subjects also appealed to French 19th century porcelain artists at Sevres and found favor at Minton in England, thanks to the émigré artist Leon Arnoux. He designed many ornate vases in Sèvres style for the Great Exhibition of 1851, some of which were painted with putti in Boucher style. The continued exodus of artists from France to Minton ensured that the Sèvres style continued with an abundance of putti. Antonin Boullemier, son of a Sèvres artist, joined Minton in 1872 where he became one of their highest-paid artists. He painted a dessert service with 250 putti for the Prince of Wales for his use at Windsor Castle.

Pate-sur-Pate Putti

Marc Louis Solon brought his skills in pâte-sur-pâte decoration from Sèvres to Minton in 1870 and he reveled in depicting diaphanously clad Grecian goddesses accompanied by Erotes symbolizing the many facets of love. Solon’s delightful sense of humor can be seen in his putti enjoying sporting activities, such as the Tug of War panel, a recent gift from Joanne Wolfe Starr.

Solon trained several Minton apprentices in his painstaking pâte-sur-pâte process, including Alboin Birks who produced a Golden Jubilee vase for Queen Victoria, which took him 93 days to complete. Birks was responsible for one of the most extraordinary putti designs at WMODA. The vase depicts a Greek goddess, probably Aphrodite, conjuring up a swarm of flying Erotes in a large cauldron licked by large flames. She holds the lid of her cooking pot in one hand and in the other she has a toasting fork testing to see if they are done yet. Some exquisite pâte-sur-pâte putti were produced by Solon’s trainees at other Stoke-on-Trent factories such as Doulton and George Jones as can be seen at WMODA.

Emblems of Love

Not surprisingly, putti as emblems of love were incorporated into Doulton’s prestigious Love Vase, which made its debut at the Chicago exhibition of 1893. The vase was modeled by Charles J. Noke and the putti were painted by the distinguished French artist Charles Labarre. Exquisitely painted putti were perfectly suited to the fine bone china body, first developed by Josiah Spode. In partnership with William Copeland, the Spode factory produced beautiful china ornaments, often decorated with putti. The extravagant putti clock at WMODA was formerly in the Copeland family collection.

Majolica Mania

The revival of interest in Renaissance maiolica painting in the mid-19th century led to the development of Victorian Majolica wares, perhaps the most popular innovation in ceramic art. Vividly colored sculptures of putti were incorporated into all sorts of ornamental and practical designs made by the Minton, Wedgwood and George Jones factories. For the dinner table, putti supported fruit bowls, sweetmeat trays, and seafood dishes, and symbolized abundance with their oversize cornucopia, baskets and conch shells. One of the most bizarre Majolica sculptures at WMODA is by Georges Pull of France and shows a startled putto being nipped by a lobster.

Heart to Hand

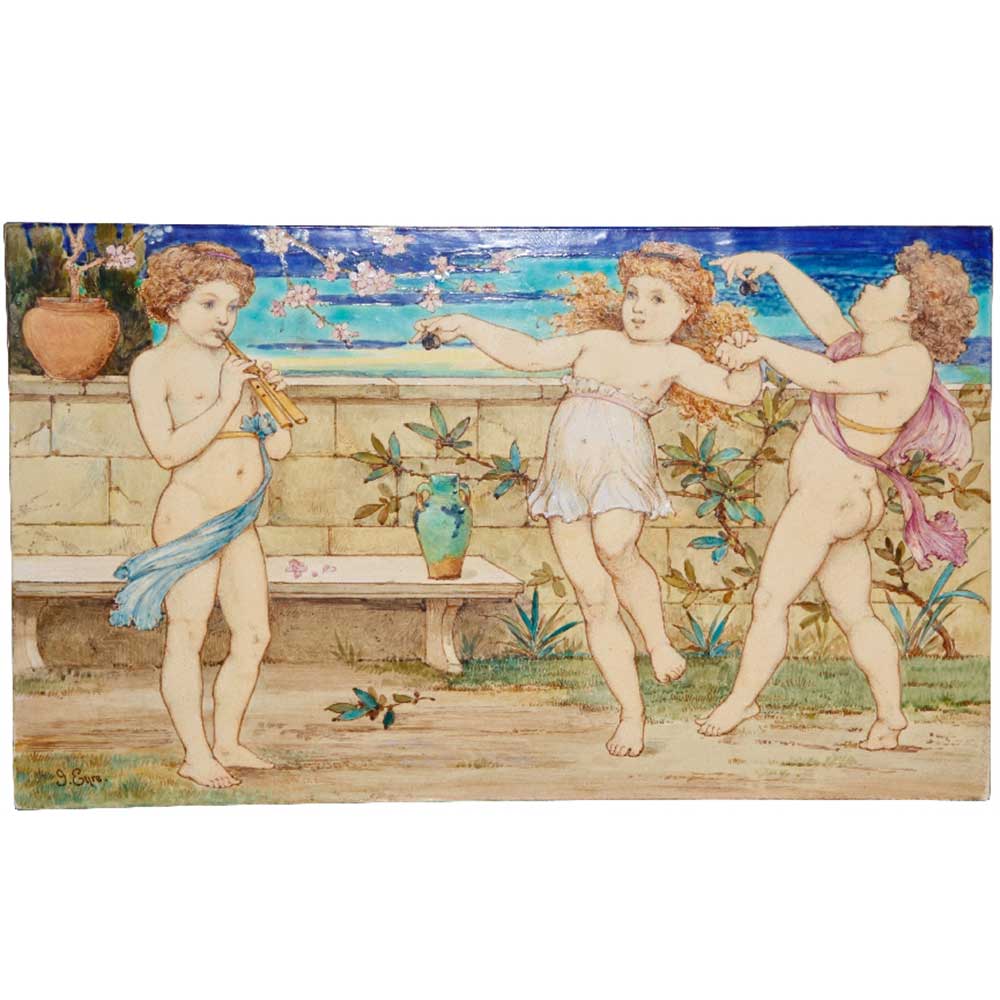

Putti proved to be popular subject matter in Victorian art pottery and were hand-painted on tiles, plaques and vases. One of the leading artists of the era was Emile Lessore, who worked originally in oils and watercolors. He began painting on pottery at Sèvres in France, moved to Minton in 1858, and then to Wedgwood, where his paintings on Queens ware won him many accolades and exhibition medals. William S. Coleman, a successful artist and book illustrator, was so heavily influenced by classical art that his style was dubbed “toga and terrace”. Coleman moved to the Staffordshire potteries to learn how to paint on pottery in 1869, first at Copeland and then at the Minton factory. He was appointed Director of the Minton Art Pottery Studio in London where young women were engaged to paint his designs. John Eyre took over responsibility for the Minton studio in 1873 until fire destroyed the building in 1875. Later he moved to Doulton and several of his putti paintings are in the WMODA collection, including his tribute to the French Renaissance potter, Bernard Palissy.

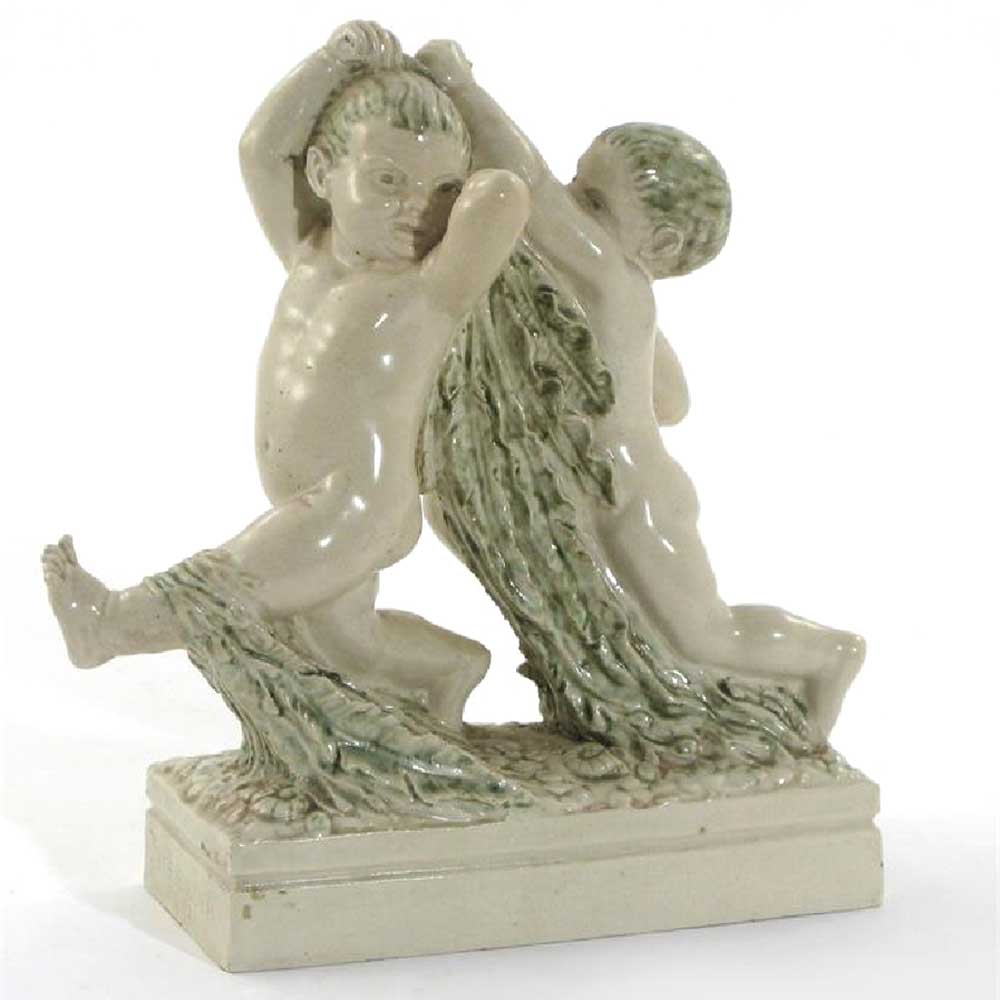

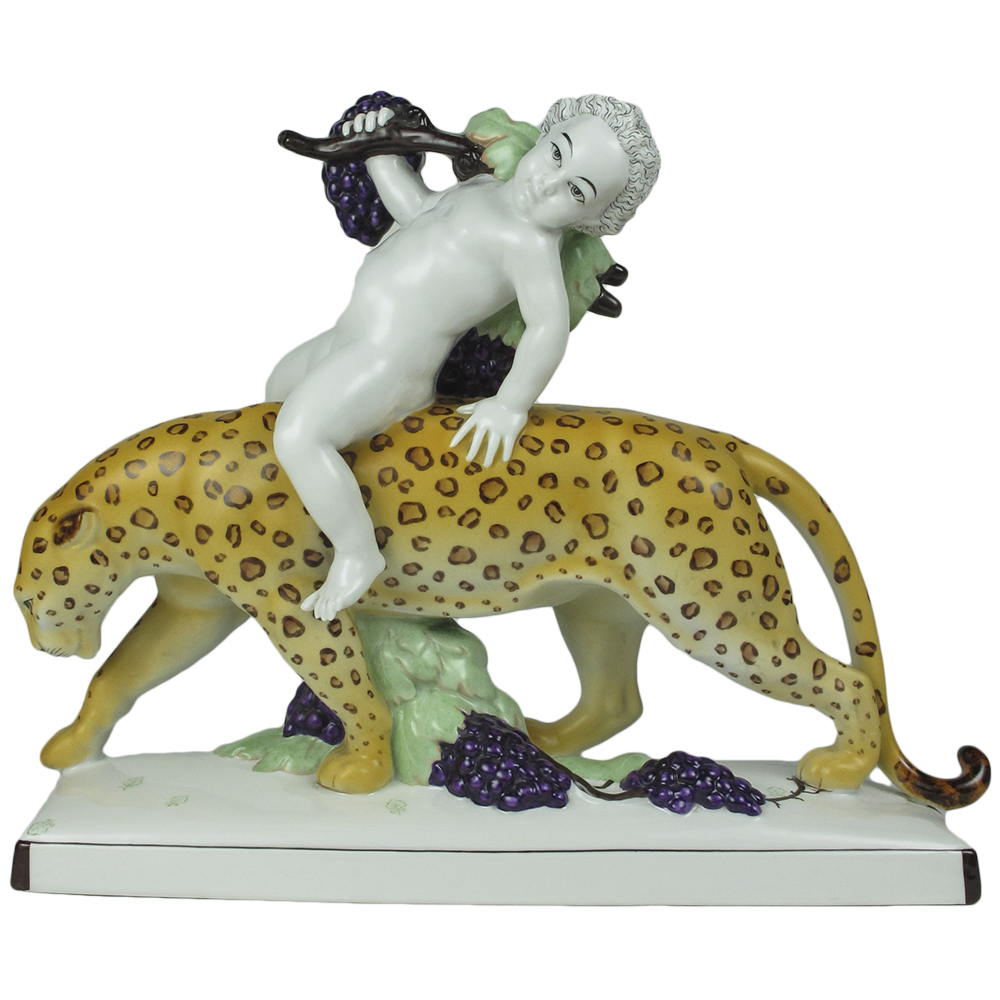

In Paris, Theodore Deck encouraged many professional artists to paint on pottery plaques and tiles, often using his brilliant turquoise ground color, which became known Bleu Deck, for their putti designs. Some of the most charming putti at WMODA were produced by the Rosenthal factory in the early 1900s. Several can be seen riding on insects and animals in our Fantastique exhibition along with their fairy friends. They also frolic in ceramic figures by British sculptors in the 1920s, such as Charles Vyse and Harry Parr.

Read more about Pate-sur-Pate Porcelain

A Starr Gift

Read more about Meissen

Myths & Meissen

Read more about the Minton in

Over the Moon

George Jones Infant Neptune @ WMODA

George Jones Infant Neptune

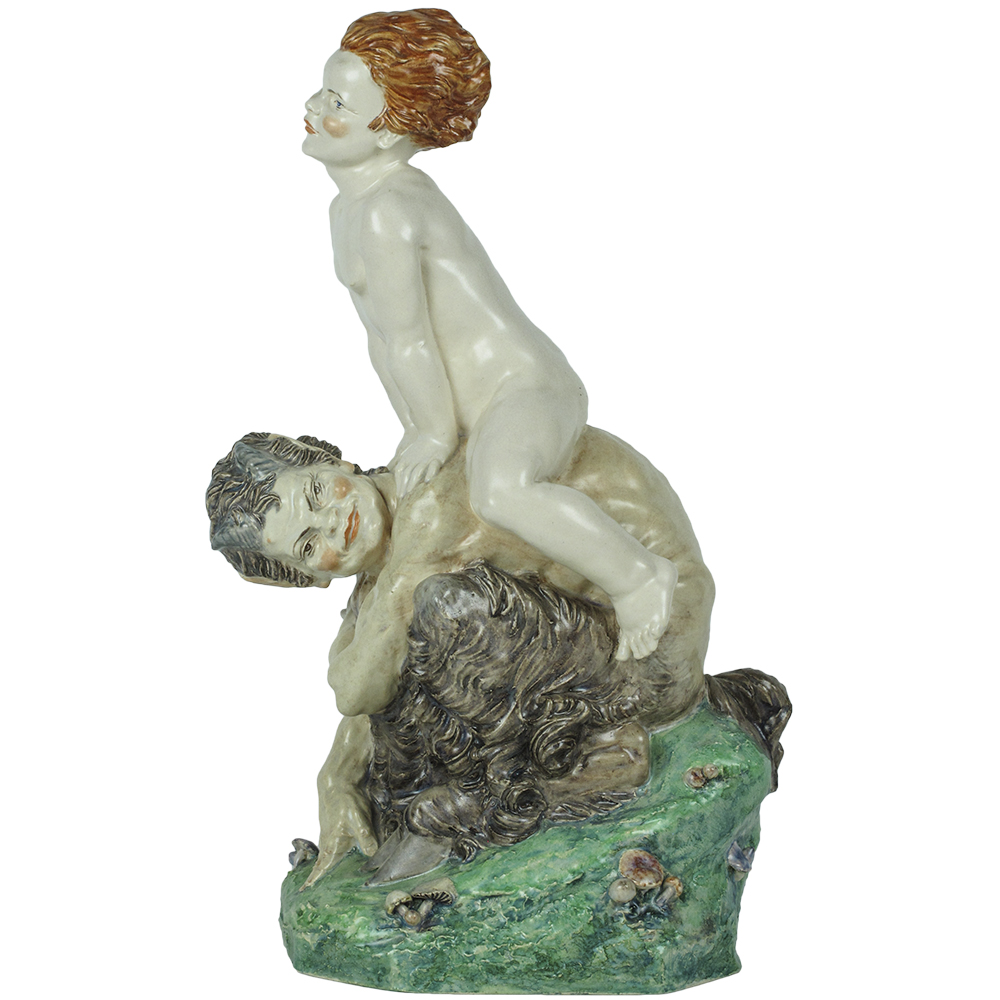

Leap Frog by C. Vyse

Rosenthal Pan and Child on Tortoise

Meissen Painting Class

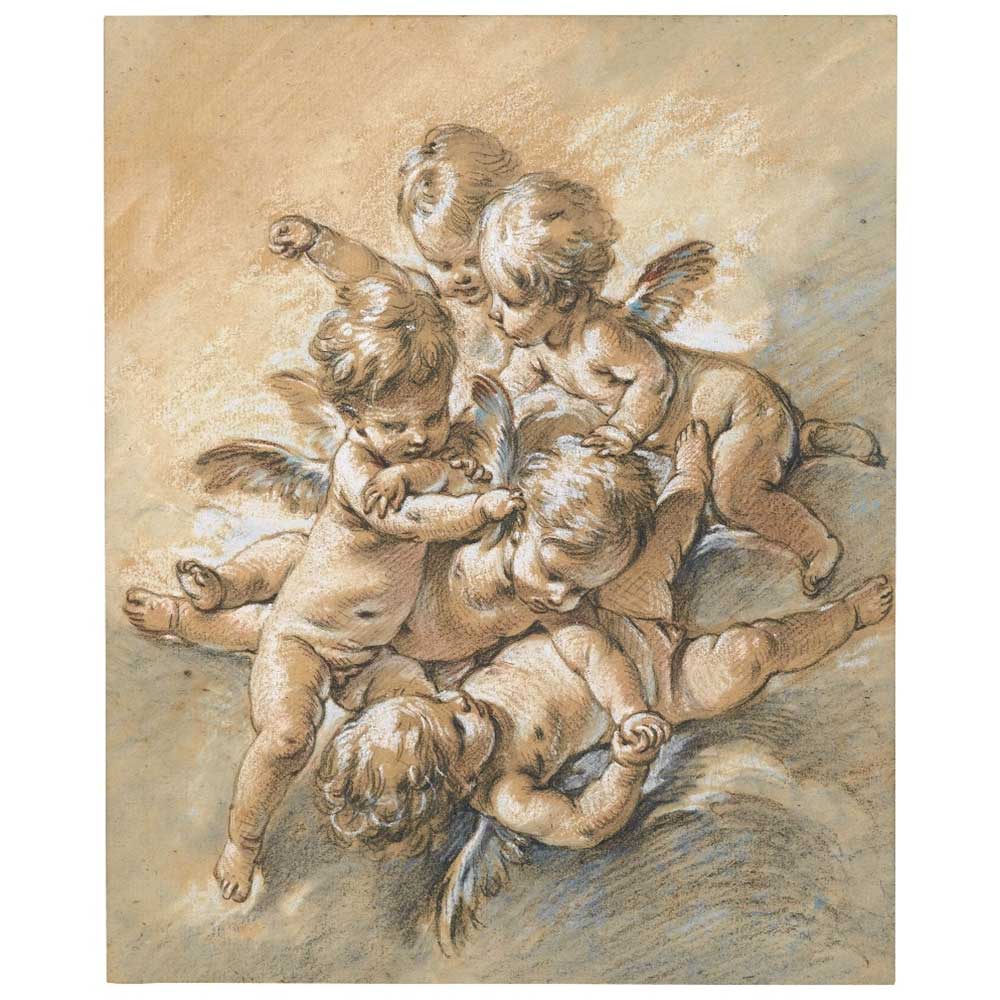

Geniuses of Art by F. Boucher

Allegory of Painting by F. Boucher

Hutschenreuther Venus Adorned

Venus and Erotes by E. Lessore

Roman Sarcophagus

Titienne by E. Lessore

Titian Detail

Bacchanal with a Lavarte Putto by Dusquenoy

Mayer BlacK Basalt Bacchanal Panel

Wedgwood Blind Man's Bluff Panel

Wedgwood Boys at Play Panel

Wedgwood Four Seasons Panel

Wedgwood Marriage of Cupid and Psyche and Sacrifice to Hymen

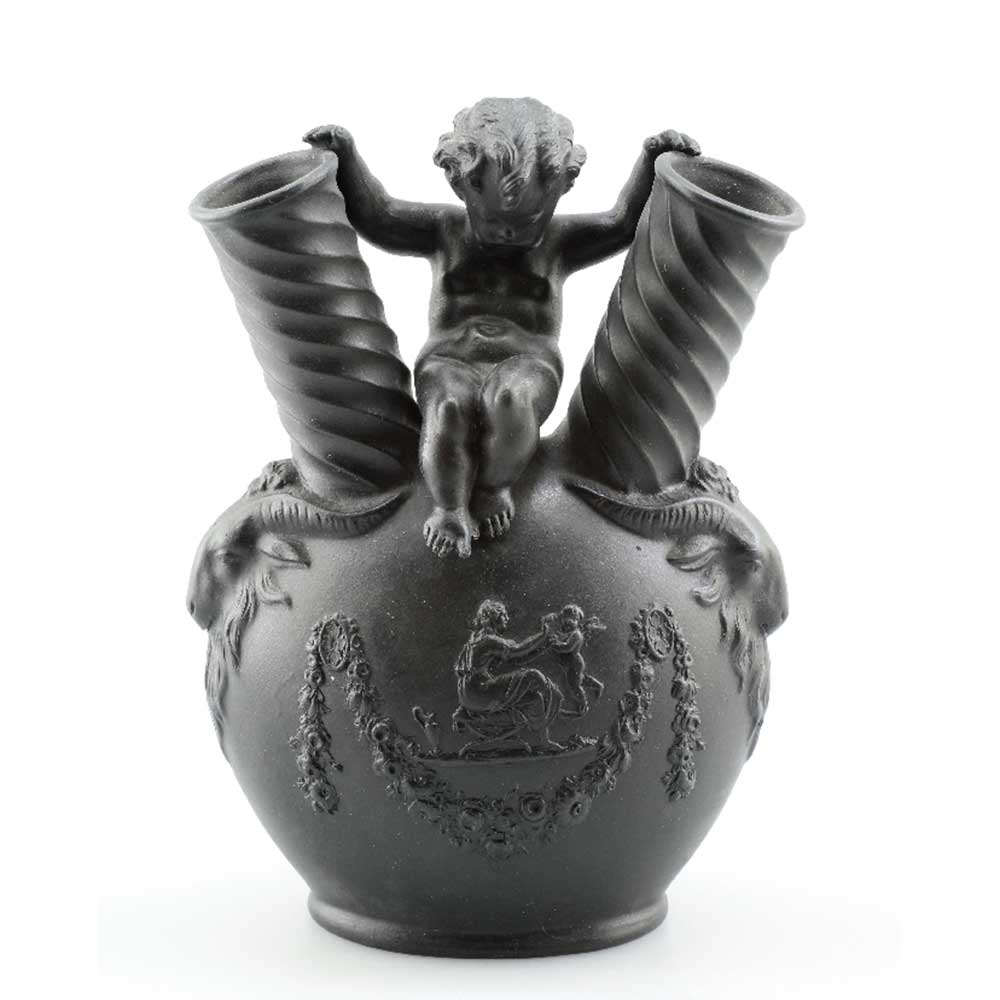

Wedgwood Black Basalt Putto

Wedgwood Jasper ware Putti

Wedgwood Sacrifice to Hymen Jug

Wedgwood Bacchanalian Boys Jug

Meissen Air

Dresden Vase detail

Dresden Vase

Minton Sevres Style Vase

Minton Sevres Style Vase detail

Minton Putto with Fan

French Champleve Tray

Putti by F. Boucher

Minton Pâte-sur-Pâte Exhibition Vase by A. Birks

Minton Pâte-sur-Pâte Exhibition Vase detail

Royal Doulton Pâte-sur-Pâte Vases

Minton Tug-of-War by L. Solon

Minton Tug-of-War detail

Royal Doulton Pâte-sur-Pâte Tyg by A. Morgan

Doulton Love Vase by C. Labarre

Copeland Clock

Spode Pot Pourri

Lobster Boy by G. Pull

Minton Majolica Boy with Basket

Italian Maiolica Vulcan, Venus & Erotes photo courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum

Minton Majolica Cornucopia

Minton Majolica Putti Vase

Minton Majolica Ewer by H. Protat

Minton Majolica Putto Hippocamp

Minton Majolica Laborers

Wedgwood Majolica Wall Bracket

Italian Maiolica

Minton Putto by M. Gladstone

Minton Putto by M. Gladstone

Queensware Mermaid Vase by Pepin

Minton Compote by E. Lessore

Minton Plaque by A. E. Black

Minton Tile by J. Eyre

Cupid & Psyche Tile

Wedgwood Spring Plaque

Minton Putto by A. Boullemier

Wedgwood Venus and Cherubs by E. Lessore

Doulton Faience Plaque by J. Eyre

Rosenthal Boy with Crab

Rosenthal Summer Ride by A. Caasmann

Putti by J. Bidder

Volkstedt Curiosity

Boy with Turkey by H. Parr

Fraureuth Putto on Leopard by M. H. Fritz

Theodore Deck Plaque by S. Schaeppi

Theodore Deck Plaque by J. Legrain